The following article introduces WASM GC: bringing garbage collection to Web Assembly. It explains topics such as memory fragmentation, inlining and VM compilation.

https://v8.dev/blog/wasm-gc-porting

A recent article on WebAssembly Garbage Collection (WasmGC) explains at a high level how the Garbage Collection (GC) proposal aims to better support GC languages in Wasm, which is very important given their popularity. In this article, we will get into the technical details of how GC languages such as Java, Kotlin, Dart, Python, and C# can be ported to Wasm. There are in fact two main approaches:

- The “traditional” porting approach, in which an existing implementation of the language is compiled to WasmMVP, that is, the WebAssembly Minimum Viable Product that launched in 2017.

- The WasmGC porting approach, in which the language is compiled down to GC constructs in Wasm itself that are defined in the recent GC proposal.

We’ll explain what those two approaches are and the technical tradeoffs between them, especially regarding size and speed. While doing so, we’ll see that WasmGC has several major advantages, but it also requires new work both in toolchains and in Virtual Machines (VMs). The later sections of this article will explain what the V8 team has been doing in those areas, including benchmark numbers. If you’re interested in Wasm, GC, or both, we hope you’ll find this interesting, and make sure to check out the demo and getting started links near the end!

The “Traditional” Porting Approach

How are languages typically ported to new architectures? Say that Python wants to run on the ARM architecture, or Dart wants to run on the MIPS architecture. The general idea is then to recompile the VM to that architecture. Aside from that, if the VM has architecture-specific code, like just-in-time (JIT) or ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation, then you also implement a backend for JIT/AOT for the new architecture. This approach makes a lot of sense, because often the main part of the codebase can just be recompiled for each new architecture you port to:

On the left, main runtime code including a parser, garbage collector, optimizer, library support, and more; on the right, separate backend code for x64, ARM, etc.

Structure of a ported VM

In this figure, the parser, library support, garbage collector, optimizer, etc., are all shared between all architectures in the main runtime. Porting to a new architecture only requires a new backend for it, which is a comparatively small amount of code.

Wasm is a low-level compiler target and so it is not surprising that the traditional porting approach can be used. Since Wasm first started we have seen this work well in practice in many cases, such as Pyodide for Python and Blazor for C# (note that Blazor supports both AOT and JIT compilation, so it is a nice example of all the above). In all these cases, a runtime for the language is compiled into WasmMVP just like any other program that is compiled to Wasm, and so the result uses WasmMVP’s linear memory, table, functions, and so forth.

As mentioned before, this is how languages are typically ported to new architectures, so it makes a lot of sense for the usual reason that you can reuse almost all the existing VM code, including language implementation and optimizations. It turns out, however, that there are several Wasm-specific downsides to this approach, and that is where WasmGC can help.

The WasmGC Porting Approach

Briefly, the GC proposal for WebAssembly (“WasmGC”) allows you to define struct and array types and perform operations such as create instances of them, read from and write to fields, cast between types, etc. (for more details, see the proposal overview). Those objects are managed by the Wasm VM’s own GC implementation, which is the main difference between this approach and the traditional porting approach.

It may help to think of it like this: If the traditional porting approach is how one ports a language to an architecture, then the WasmGC approach is very similar to how one ports a language to a VM. For example, if you want to port Java to JavaScript, then you can use a compiler like J2CL which represents Java objects as JavaScript objects, and those JavaScript objects are then managed by the JavaScript VM just like all others. Porting languages to existing VMs is a very useful technique, as can be seen by all the languages that compile to JavaScript, the JVM, and the CLR.

This architecture/VM metaphor is not an exact one, in particular because WasmGC intends to be lower-level than the other VMs we mentioned in the last paragraph. Still, WasmGC defines VM-managed structs and arrays and a type system for describing their shapes and relationships, and porting to WasmGC is the process of representing your language’s constructs with those primitives; this is certainly higher-level than a traditional port to WasmMVP (which lowers everything into untyped bytes in linear memory). Thus, WasmGC is quite similar to ports of languages to VMs, and it shares the advantages of such ports, in particular good integration with the target VM and reuse of its optimizations.

Comparing the Two Approaches

Now that we have an idea of what the two porting approaches for GC languages are, let’s see how they compare.

Shipping memory management code

In practice, a lot of Wasm code is run inside a VM that already has a garbage collector, which is the case on the Web, and also in runtimes like Node.js, workerd, Deno, and Bun. In such places, shipping a GC implementation adds unnecessary size to the Wasm binary. In fact, this is not just a problem with GC languages in WasmMVP, but also with languages using linear memory like C, C++, and Rust, since code in those languages that does any sort of interesting allocation will end up bundling malloc/free to manage linear memory, which requires several kilobytes of code. For example, dlmalloc requires 6K, and even a malloc that trades off speed for size, like emmalloc, takes over 1K. WasmGC, on the other hand, has the VM automatically manage memory for us so we need no memory management code at all—neither a GC nor malloc/free—in the Wasm. In the previously-mentioned article on WasmGC, the size of the fannkuch benchmark was measured and WasmGC was much smaller than C or Rust—2.3 K vs 6.1-9.6 K—for this exact reason.

Cycle collection

In browsers, Wasm often interacts with JavaScript (and through JavaScript, Web APIs), but in WasmMVP (and even with the reference types proposal) there is no way to have bidirectional links between Wasm and JS that allow cycles to be collected in a fine-grained manner. Links to JS objects can only be placed in the Wasm table, and links back to the Wasm can only refer to the entire Wasm instance as a single big object, like this:

Individual JS objects refer to a single big Wasm instance, and not to individual objects inside it.

Cycles between JS and an entire Wasm module

That is not enough to efficiently collect specific cycles of objects where some happen to be in the compiled VM and some in JavaScript. With WasmGC, on the other hand, we define Wasm objects that the VM is aware of, and so we can have proper references from Wasm to JavaScript and back:

JS and Wasm objects with links between them.

Cycles between JS and WasmGC objects

GC references on the stack

GC languages must be aware of references on the stack, that is, from local variables in a call scope, as such references may be the only thing keeping an object alive. In a traditional port of a GC language that is a problem because Wasm’s sandboxing prevents programs from inspecting their own stack. There are solutions for traditional ports, like a shadow stack (which can be done automatically), or only collecting garbage when nothing is on the stack (which is the case in between turns of the JavaScript event loop). A possible future addition which would help traditional ports might be stack scanning support in Wasm. For now, only WasmGC can handle stack references without overhead, and it does so completely automatically since the Wasm VM is in charge of GC.

GC Efficiency

A related issue is the efficiency of performing a GC. Both porting approaches have potential advantages here. A traditional port can reuse optimizations in an existing VM that may be tailored to a particular language, such as a heavy focus on optimizing interior pointers or short-lived objects. A WasmGC port that runs on the Web, on the other hand, has the advantage of reusing all the work that has gone into making JavaScript GC fast, including techniques like generational GC, incremental collection, etc. WasmGC also leaves GC to the VM, which makes things like efficient write barriers simpler.

Another advantage of WasmGC is that the GC can be aware of things like memory pressure and can adjust its heap size and collection frequency accordingly, again, as JavaScript VMs already do on the Web.

Memory fragmentation

Over time, and especially in long-running programs, malloc/free operations on WasmMVP linear memory can cause fragmentation. Imagine that we have a total of 2 MB of memory, and right in the middle of it we have an existing small allocation of only a few bytes. In languages like C, C++, and Rust it is impossible to move an arbitrary allocation at runtime, and so we have almost 1MB to the left of that allocation and almost 1MB to the right. But those are two separate fragments, and so if we try to allocate 1.5 MB we will fail, even though we do have that amount of total unallocated memory:

A linear memory with a rude small allocation right in the middle, splitting the free space into 2 halves.

Such fragmentation can force a Wasm module to grow its memory more often, which adds overhead and can cause out-of-memory errors; improvements are being designed, but it is a challenging problem. This is an issue in all WasmMVP programs, including traditional ports of GC languages (note that the GC objects themselves might be movable, but not parts of the runtime itself). WasmGC, on the other hand, avoids this issue because memory is completely managed by the VM, which can move them around to compact the GC heap and avoid fragmentation.

Developer tools integration

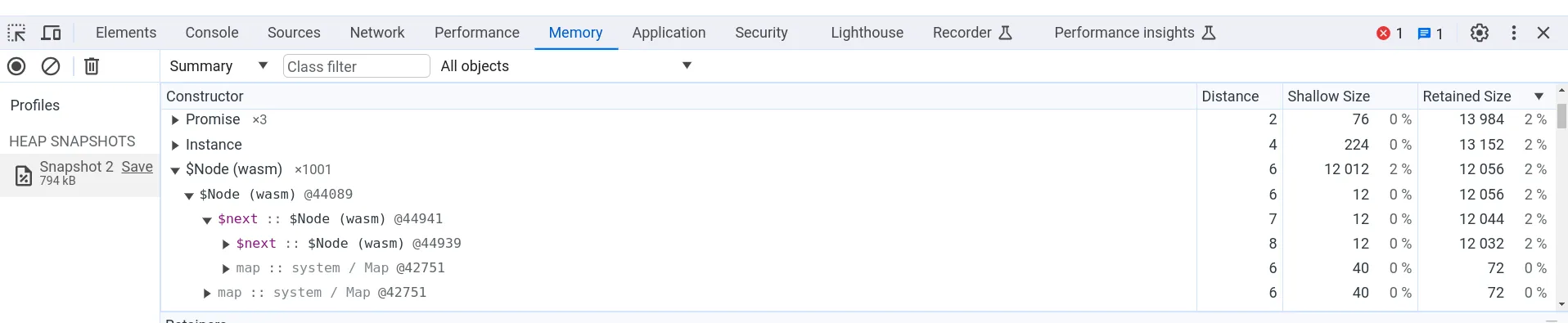

In a traditional port to WasmMVP, objects are placed in linear memory which is hard for developer tools to provide useful information about, because such tools only see bytes without high-level type information. In WasmGC, on the other hand, the VM manages GC objects so better integration is possible. For example, in Chrome you can use the heap profiler to measure memory usage of a WasmGC program:

WasmGC code running in the Chrome heap profiler

The figure above shows the Memory tab in Chrome DevTools, where we have a heap snapshot of a page that ran WasmGC code that created 1,001 small objects in a linked list. You can see the name of the object’s type, $Node, and the field $next which refers to the next object in the list. All the usual heap snapshot information is present, like the number of objects, the shallow size, the retained size, and so forth, letting us easily see how much memory is actually used by WasmGC objects. Other Chrome DevTools features like the debugger work as well on WasmGC objects.

Language Semantics

When you recompile a VM in a traditional port you get the exact language you expect, since you’re running familiar code that implements that language. That’s a major advantage! In comparison, with a WasmGC port you may end up considering compromises in semantics in return for efficiency. That is because with WasmGC we define new GC types—structs and arrays—and compile to them. As a result, we can’t simply compile a VM written in C, C++, Rust, or similar languages to that form, since those only compile to linear memory, and so WasmGC can’t help with the great majority of existing VM codebases. Instead, in a WasmGC port you typically write new code that transforms your language’s constructs into WasmGC primitives. And there are multiple ways to do that transformation, with different tradeoffs.

Whether compromises are needed or not depends on how a particular language’s constructs can be implemented in WasmGC. For example, WasmGC struct fields have fixed indexes and types, so a language that wishes to access fields in a more dynamic manner may have challenges; there are various ways to work around that, and in that space of solutions some options may be simpler or faster but not support the full original semantics of the language. (WasmGC has other current limitations as well, for example, it lacks interior pointers; over time such things are expected to improve.)

As we’ve mentioned, compiling to WasmGC is like compiling to an existing VM, and there are many examples of compromises that make sense in such ports. For example, dart2js (Dart compiled to JavaScript) numbers behave differently than in the Dart VM, and IronPython (Python compiled to .NET) strings behave like C# strings. As a result, not all programs of a language may run in such ports, but there are good reasons for these choices: Implementing dart2js numbers as JavaScript numbers lets VMs optimize them well, and using .NET strings in IronPython means you can pass those strings to other .NET code with no overhead.

While compromises may be needed in WasmGC ports, WasmGC also has some advantages as a compiler target compared to JavaScript in particular. For example, while dart2js has the numeric limitations we just mentioned, dart2wasm (Dart compiled to WasmGC) behaves exactly as it should, without compromise (that is possible since Wasm has efficient representations for the numeric types Dart requires).

Why isn’t this an issue for traditional ports? Simply because they recompile an existing VM into linear memory, where objects are stored in untyped bytes, which is lower-level than WasmGC. When all you have are untyped bytes then you have a lot more flexibility to do all manner of low-level (and potentially unsafe) tricks, and by recompiling an existing VM you get all the tricks that VM has up its sleeve.

Toolchain Effort

As we mentioned in the previous subsection, a WasmGC port cannot simply recompile an existing VM. You might be able to reuse certain code (such as parser logic and AOT optimizations, because those don’t integrate with the GC at runtime), but in general WasmGC ports require a substantial amount of new code.

In comparison, traditional ports to WasmMVP can be simpler and quicker: for example, you can compile the Lua VM (written in C) to Wasm in just a few minutes. A WasmGC port of Lua, on the other hand, would require more effort as you’d need to write code to lower Lua’s constructs into WasmGC structs and arrays, and you’d need to decide how to actually do that within the specific constraints of the WasmGC type system.

Greater toolchain effort is therefore a significant disadvantage of WasmGC porting. However, given all the advantages we’ve mentioned earlier, we think WasmGC is still very appealing! The ideal situation would be one in which WasmGC’s type system could support all languages efficiently, and all languages put in the work to implement a WasmGC port. The first part of that will be helped by future additions to the WasmGC type system, and for the second, we can reduce the work involved in WasmGC ports by sharing the effort on the toolchain side as much as possible. Luckily, it turns out that WasmGC makes it very practical to share toolchain work, which we’ll see in the next section.

Optimizing WasmGC

We’ve already mentioned that WasmGC ports have potential speed advantages, such as using less memory and reusing optimizations in the host GC. In this section we’ll show other interesting optimization advantages of WasmGC over WasmMVP, which can have a large impact on how WasmGC ports are designed and how fast the final results are.

The key issue here is that WasmGC is higher-level than WasmMVP. To get an intuition for that, remember that we’ve already said that a traditional port to WasmMVP is like porting to a new architecture while a WasmGC port is like porting to a new VM, and VMs are of course higher-level abstractions over architectures—and higher-level representations are often more optimizable. We can perhaps see this more clearly with a concrete example in pseudocode:

func foo() { let x = allocate<T>(); // Allocate a GC object. x.val = 10; // Set a field to 10. let y = allocate<T>(); // Allocate another object. y.val = x.val; // This must be 10. return y.val; // This must also be 10.}

As the comments indicate, x.val will contain 10, as will y.val, so the final return is of 10 as well, and then the optimizer can even remove the allocations, leading to this:

func foo() { return 10;}

Great! Sadly, however, that is not possible in WasmMVP, because each allocation turns into a call to malloc, a large and complex function in the Wasm which has side effects on linear memory. As a result of those side effects, the optimizer must assume that the second allocation (for y) might alter x.val, which also resides in linear memory. Memory management is complex, and when we implement it inside the Wasm at a low level then our optimization options are limited.

In contrast, in WasmGC we operate at a higher level: each allocation executes the struct.new instruction, a VM operation that we can actually reason about, and an optimizer can track references as well to conclude that x.val is written exactly once with the value 10. As a result we can optimize that function down to a simple return of 10 as expected!

Aside from allocations, other things WasmGC adds are explicit function pointers (ref.func) and calls using them (call_ref), types on struct and array fields (unlike untyped linear memory), and more. As a result, WasmGC is a higher-level Intermediate Representation (IR) than WasmMVP, and much more optimizable.

If WasmMVP has limited optimizability, why is it as fast as it is? Wasm, after all, can run pretty close to full native speed. That is because WasmMVP is generally the output of a powerful optimizing compiler like LLVM. LLVM IR, like WasmGC and unlike WasmMVP, has a special representation for allocations and so forth, so LLVM can optimize the things we’ve been discussing. The design of WasmMVP is that most optimizations happen at the toolchain level before Wasm, and Wasm VMs only do the “last mile” of optimization (things like register allocation).

Can WasmGC adopt a similar toolchain model as WasmMVP, and in particular use LLVM? Unfortunately, no, since LLVM does not support WasmGC (some amount of support has been explored, but it is hard to see how full support could even work). Also, many GC languages do not use LLVM–there is a wide variety of compiler toolchains in that space. And so we need something else for WasmGC.

Luckily, as we’ve mentioned, WasmGC is very optimizable, and that opens up new options. Here is one way to look at that:

WasmMVP and WasmGC toolchain workflows

Both the WasmMVP and WasmGC workflows begin with the same two boxes on the left: we start with source code that is processed and optimized in a language-specific manner (which each language knows best about itself). Then a difference appears: for WasmMVP we must perform general-purpose optimizations first and then lower to Wasm, while for WasmGC we have the option to first lower to Wasm and optimize later. This is important because there is a large advantage to optimizing after lowering: then we can share toolchain code for general-purpose optimizations between all languages that compile to WasmGC. The next figure shows what that looks like:

Several languages on the left compile to WasmGC in the middle, and all that flows into the Binaryen optimizer (wasm-opt).

Multiple WasmGC toolchains are optimized by the Binaryen optimizer

Since we can do general optimizations after compiling to WasmGC, a Wasm-to-Wasm optimizer can help all WasmGC compiler toolchains. For this reason the V8 team has invested in WasmGC in Binaryen, which all toolchains can use as the wasm-opt commandline tool. We’ll focus on that in the next subsection.

Toolchain optimizations

Binaryen, the WebAssembly toolchain optimizer project, already had a wide range of optimizations for WasmMVP content such as inlining, constant propagation, dead code elimination, etc., almost all of which also apply to WasmGC. However, as we mentioned before, WasmGC allows us to do a lot more optimizations than WasmMVP, and we have written a lot of new optimizations accordingly:

- Escape analysis to move heap allocations to locals.

- Devirtualization to turn indirect calls into direct ones (that can then be inlined, potentially).

- More powerful global dead code elimination.

- Whole-program type-aware content flow analysis (GUFA).

- Cast optimizations such as removing redundant casts and moving them to earlier locations.

- Type pruning.

- Type merging.

- Type refining (for locals, globals, fields, and signatures).

That’s just a quick list of some of the work we’ve been doing. For more on Binaryen’s new GC optimizations and how to use them, see the Binaryen docs.

To measure the effectiveness of all those optimizations in Binaryen, let’s look at Java performance with and without wasm-opt, on output from the J2Wasm compiler which compiles Java to WasmGC:

Box2D, DeltaBlue, RayTrace, and Richards benchmarks, all showing an improvement with wasm-opt.

Java performance with and without wasm-opt

Here, “without wasm-opt” means we do not run Binaryen’s optimizations, but we do still optimize in the VM and in the J2Wasm compiler. As shown in the figure, wasm-opt provides a significant speedup on each of these benchmarks, on average making them 1.9× faster.

In summary, wasm-opt can be used by any toolchain that compiles to WasmGC and it avoids the need to reimplement general-purpose optimizations in each. And, as we continue to improve Binaryen’s optimizations, that will benefit all toolchains that use wasm-opt, just like improvements to LLVM help all languages that compile to WasmMVP using LLVM.

Toolchain optimizations are just one part of the picture. As we will see next, optimizations in Wasm VMs are also absolutely critical.

V8 optimizations

As we’ve mentioned, WasmGC is more optimizable than WasmMVP, and not only toolchains can benefit from that but also VMs. And that turns out to be important because GC languages are different from the languages that compile to WasmMVP. Consider inlining, for example, which is one of the most important optimizations: Languages like C, C++, and Rust inline at compile time, while GC languages like Java and Dart typically run in a VM that inlines and optimizes at runtime. That performance model has affected both language design and how people write code in GC languages.

For example, in a language like Java, all calls begin as indirect (a child class can override a parent function, even when calling a child using a reference of the parent type). We benefit whenever the toolchain can turn an indirect call into a direct one, but in practice code patterns in real-world Java programs often have paths that actually do have lots of indirect calls, or at least ones that cannot be inferred statically to be direct. To handle those cases well, we’ve implemented speculative inlining in V8, that is, indirect calls are noted as they occur at runtime, and if we see that a call site has fairly simple behavior (few call targets), then we inline there with appropriate guard checks, which is closer to how Java is normally optimized than if we left such things entirely to the toolchain.

Real-world data validates that approach. We measured performance on the Google Sheets Calc Engine, which is a Java codebase that is used to compute spreadsheet formulas, which until now has been compiled to JavaScript using J2CL. The V8 team has been collaborating with Sheets and J2CL to port that code to WasmGC, both because of the expected performance benefits for Sheets, and to provide useful real-world feedback for the WasmGC spec process. Looking at performance there, it turns out that speculative inlining is the most significant individual optimization we’ve implemented for WasmGC in V8, as the following chart shows:

WasmGC latency without opts, with other opts, with speculative inlining, and with speculative inlining + other opts. The largest improvement by far is to add speculative inlining.

Java performance with different V8 optimizations

“Other opts” here means optimizations aside from speculative inlining that we could disable for measurement purposes, which includes: load elimination, type-based optimizations, branch elimination, constant folding, escape analysis, and common subexpression elimination. “No opts” means we’ve switched off all of those as well as speculative inlining (but other optimizations exist in V8 which we can’t easily switch off; for that reason the numbers here are only an approximation). The very large improvement due to speculative inlining—about a 30% speedup(!)—compared to all the other opts together shows how important inlining is at least on compiled Java.

Aside from speculative inlining, WasmGC builds upon the existing Wasm support in V8, which means it benefits from the same optimizer pipeline, register allocation, tiering, and so forth. In addition to all that, specific aspects of WasmGC can benefit from additional optimizations, the most obvious of which is to optimize the new instructions that WasmGC provides, such as having an efficient implementation of type casts. Another important piece of work we’ve done is to use WasmGC’s type information in the optimizer. For example, ref.test checks if a reference is of a particular type at runtime, and after such a check succeeds we know that ref.cast, a cast to the same type, must also succeed. That helps optimize patterns like this in Java:

if (ref instanceof Type) { foo((Type) ref); // This downcast can be eliminated.}

These optimizations are especially useful after speculative inlining, because then we see more than the toolchain did when it produced the Wasm.

Overall, in WasmMVP there was a fairly clear separation between toolchain and VM optimizations: We did as much as possible in the toolchain and left only necessary ones for the VM, which made sense as it kept VMs simpler. With WasmGC that balance might shift somewhat, because as we’ve seen there is a need to do more optimizations at runtime for GC languages, and also WasmGC itself is more optimizable, allowing us to have more of an overlap between toolchain and VM optimizations. It will be interesting to see how the ecosystem develops here.

Demo and status

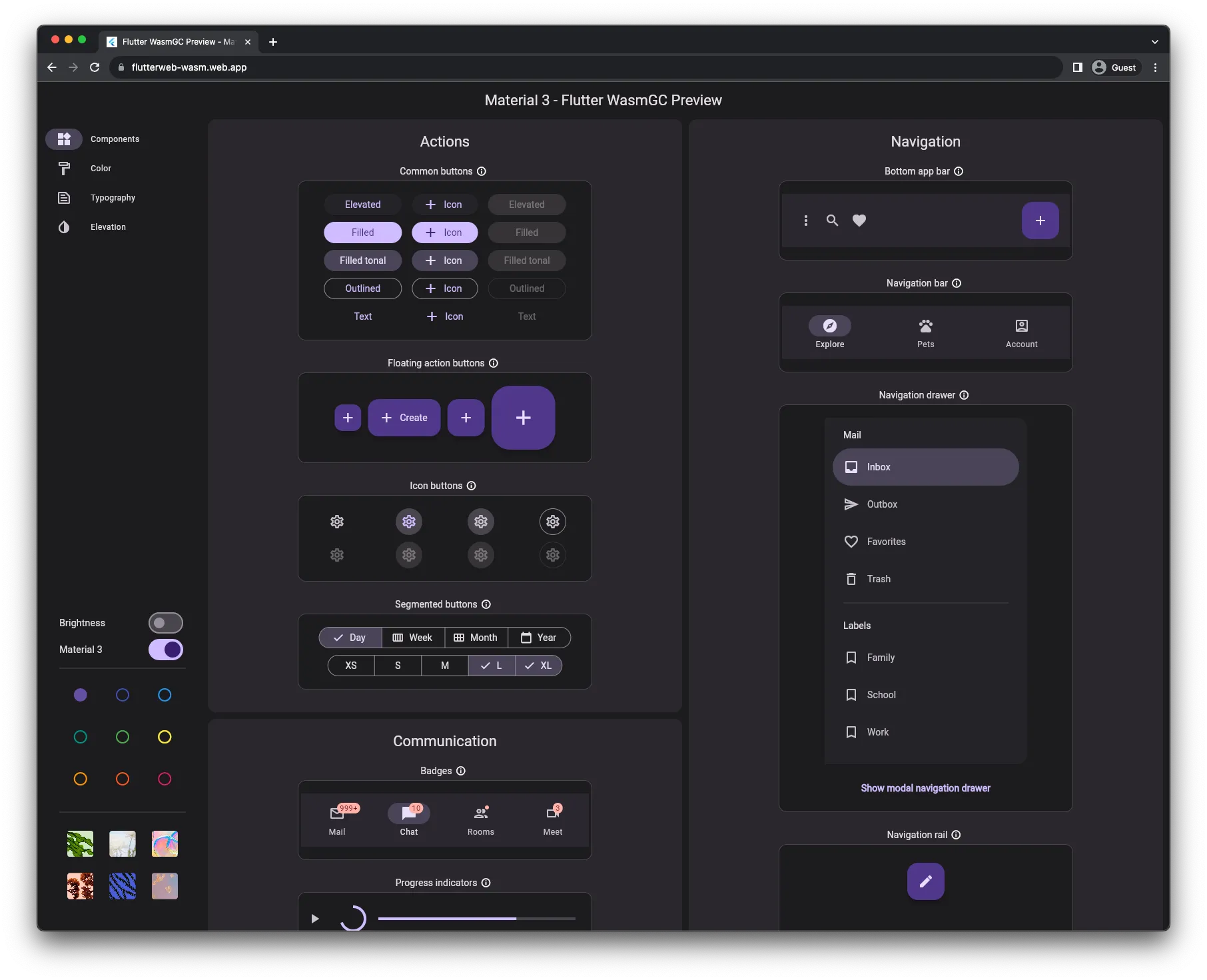

You can use WasmGC today! After reaching phase 4 at the W3C, WasmGC is now a full and finalized standard, and Chrome 119 shipped with support for it. With that browser (or any other browser that has WasmGC support; for example, Firefox 120 is expected to launch with WasmGC support later this month) you can run this Flutter demo in which Dart compiled to WasmGC drives the application’s logic, including its widgets, layout, and animation.

Material 3 rendered by Flutter WasmGC.

The Flutter demo running in Chrome 119.

Getting started

If you’re interested in using WasmGC, the following links might be useful:

- Various toolchains have support for WasmGC today, including Dart, Java (J2Wasm), Kotlin, OCaml (wasm_of_ocaml), and Scheme (Hoot).

- The source code of the small program whose output we showed in the developer tools section is an example of writing a “hello world” WasmGC program by hand. (In particular you can see the

$Nodetype defined and then created usingstruct.new.) - The Binaryen wiki has documentation about how compilers can emit WasmGC code that optimizes well. The earlier links to the various WasmGC-targeting toolchains can also be useful to learn from, for example, you can look at the Binaryen passes and flags that Java, Dart, and Kotlin use.

Summary

WasmGC is a new and promising way to implement GC languages in WebAssembly. Traditional ports in which a VM is recompiled to Wasm will still make the most sense in some cases, but we hope that WasmGC ports will become a popular technique because of their benefits: WasmGC ports have the ability to be smaller than traditional ports—even smaller than WasmMVP programs written in C, C++, or Rust—and they integrate better with the Web on matters like cycle collection, memory use, developer tooling, and more. WasmGC is also a more optimizable representation, which can provide significant speed benefits as well as opportunities to share more toolchain effort between languages.