The following is a detailed explanation on how Go concurrency model works. The author explains differentiates Goroutines from normal OS threads, what are running queues, working steal protocol and more.

https://betterprogramming.pub/deep-dive-into-concurrency-of-go-93002344d37b

According to the StackOverflow Developer Survey and the TIOBE index, Go (or Golang) has gained more traction, especially among backend developers and DevOps teams working on infrastructure automation. That’s reason enough to talk about Go and its clever way of dealing with concurrency.

Go is known for its first-class support for concurrency, or the ability for a program to deal with multiple things at once. Running code concurrently is becoming a more critical part of programming as computers move from running a single code stream faster to running more streams simultaneously.

A programmer can make their program run faster by designing it to run concurrently so that each part of the program can run independently of the others. Three features in Go, goroutines, channels, and selects, make concurrency easier when combined together.

Goroutines solve the problem of running concurrent code in a program, and channels solve the problem of communicating safely between concurrently running code.

Goroutines are without a doubt one of Go’s best features! They are very lightweight, not like OS threads, but rather hundreds of Goroutines can be multiplexed onto an OS Thread (Go has its runtime scheduler for this) with a minimal overhead of context switching! In simple terms, goroutines are a lightweight and a cheap abstraction over threads.

But how is Go’s concurrency approach working under the hood? Today, I want to try to explain this to you. This article focuses more on the orchestration of Go’s concurrency entities than on these entities themselves. So we won’t rely on too many code snippets today.

Go Runtime Scheduler

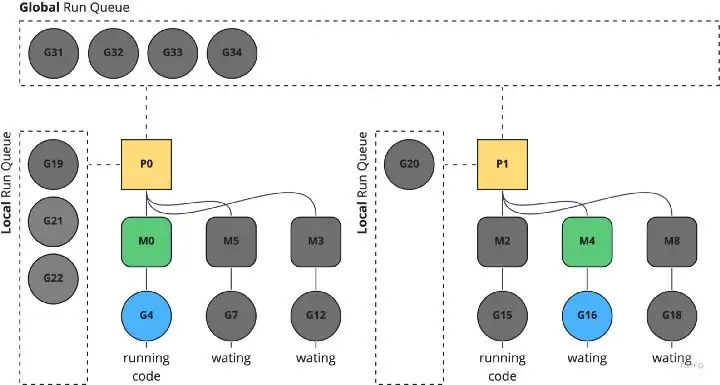

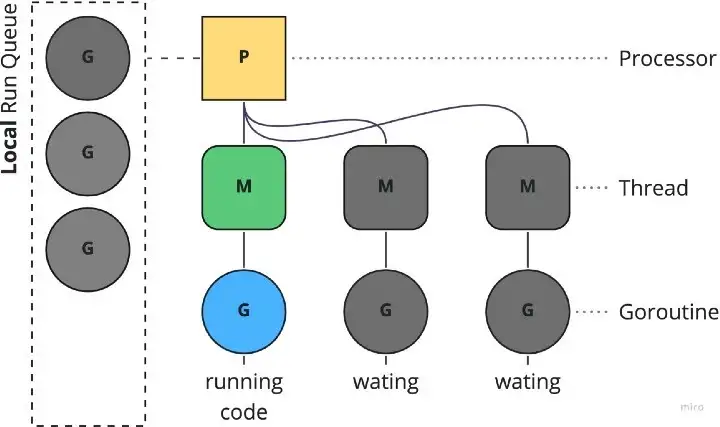

So to say, its job is to distribute runnable goroutines (G) over multiple worker OS threads (M) that run on one or more processors (P). Processors are handling multiple threads. Threads are handling multiple goroutines. Processors are hardware depended; the number of processors is set on the number of your CPU cores.

- G = Goroutine

- M = OS Thread

- P = Processor

When a new goroutine is created, or an existing goroutine becomes runnable, it is pushed onto a list of runnable goroutines of the current processor. When the processor finishes executing a goroutine, it first tries to pop a goroutine from its list of runnable goroutines. If the list is empty, the processor chooses a random processor and tries to steal half of the runnable goroutines.

What’s a Goroutine?

Goroutines are functions that run concurrently with other functions. Goroutines can be considered lightweight threads on top of an OS thread. The cost of creating a Goroutine is tiny when compared to a thread. Hence it’s common for Go applications to have thousands of Goroutines running concurrently.

Goroutines are multiplexed to a fewer number of OS threads. There might be only one thread in a program with thousands of goroutines. If any Goroutine in that thread blocks says waiting for user input, then another OS thread is created, or a parked (idled) thread is pulled, and the remaining Goroutines are moved to the created or unparked OS thread. All these are taken care of by Go’s runtime scheduler. A goroutine has three states: running, runnable, and not runnable.

Goroutines vs. Threads

Why not use simple OS threads as Go already does? That’s a fair question. As mentioned above, Goroutines are already running on top of OS threads. But the difference is that multiple Goroutines run on single OS threads.

Creating a goroutine does not require much memory, only 2kB of stack space. They grow by allocating and freeing heap storage as required. In comparison, threads start at a much larger space, along with a region of memory called a guard page that acts as a guard between one thread’s memory and another.

Goroutines are easily created and destroyed at runtime, but threads have a large setup and teardown costs; it has to request resources from the OS and return it once it’s done.

The runtime is allocated a few threads on which all the goroutines are multiplexed. At any point in time, each thread will be executing one goroutine. If that goroutine is blocked (function call, syscall, network call, etc.), it will be swapped out for another goroutine that will execute on that thread instead.

In summary, Go is using Goroutines and Threads, and both are essential in their combination of executing functions concurrently. But Go is using Goroutines makes Go a much greater programming language than it might look at first.

Goroutines Queues

Go manages goroutines at two levels, local queues and global queues. Local queues are attached to each processor, while the global queue is common.

Goroutines do not go in the global queue only when the local queue is full, and they are also pushed in it when Go injects a list of goroutines to the scheduler, e.g., from the network poller or goroutines asleep during the garbage collection.

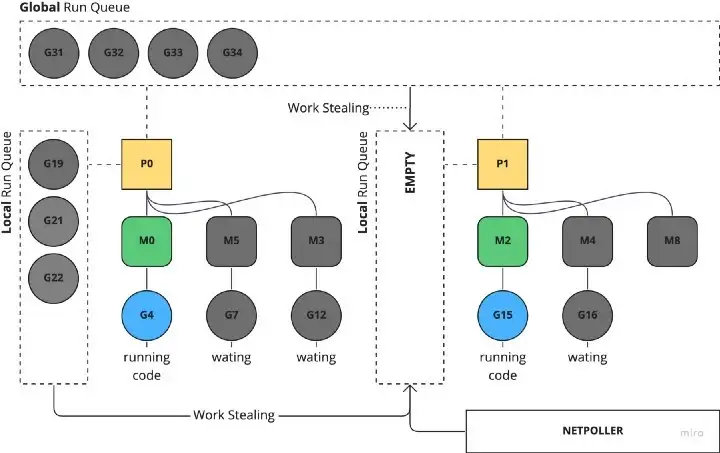

Stealing Work

When a processor does not have any Goroutines, it applies the following rules in this order:

- pull work from the own local queue

- pull work from network poller

- steal work from the other processor’s local queue

- pull work from the global queue

Since a processor can pull work from the global queue when it runs out of tasks, the first available P will run the goroutine. This behavior explains why a goroutine runs on different P and shows how Go optimizes the system by letting other goroutines run when a resource is free.

Work Stealing Diagram

In this diagram, you can see that P1 ran out of goroutines. So the Go’s runtime scheduler will take goroutines from other processors. If every other processor run queue is empty, it checks for completed IO requests (syscalls, network requests) from the netpoller. If this netpoller is empty, the processor will try to get goroutines from the global run queue.

Run and Debug

In this code snippet, we create 20 goroutine functions. Each will sleep for a second and then counting to 1e10 (10,000,000,000). Let’s debug the Go Scheduler by setting the env to GODEBUG=schedtrace=1000.

Code

package main

import (

"sync"

"time"

)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 20; i++ {

wg.Add(1) // increases WaitGroup

go work() // calls a function as goroutine

}

wg.Wait() // waits until WaitGroup is <= 0

}

func work() {

time.Sleep(time.Second)

var counter int

for i := 0; i < 1e10; i++ {

counter++

}

wg.Done()

}

Results

The results show the number of goroutines in the global queue with runqueue and the local queues (respectively P0 and P1) in the bracket [5 8 3 0]. As we can see with the grow attribute, when the local queue reaches 256 awaiting goroutines, the next ones will stack in the global queue.

gomaxprocs: Processors configuredidleprocs: Processors are not in use. Goroutine running.threads: Threads in use.idlethreads: Threads are not in use.runqueue: Goroutines in the global queue.[1 0 0 0]: Goroutines in each processor’s local run queue.

idleprocs=1 threads=6 idlethreads=0 runqueue=0 [1 0 0 0]

idleprocs=2 threads=3 idlethreads=0 runqueue=0 [0 0 0 0]

idleprocs=4 threads=9 idlethreads=2 runqueue=0 [0 0 0 0]

idleprocs=0 threads=5 idlethreads=0 runqueue=0 [5 8 3 0]

idleprocs=4 threads=9 idlethreads=2 runqueue=0 [0 0 0 0]

idleprocs=0 threads=5 idlethreads=0 runqueue=8 [2 2 1 3]

idleprocs=4 threads=9 idlethreads=2 runqueue=0 [0 0 0 0]

idleprocs=0 threads=5 idlethreads=0 runqueue=10 [3 1 0 2]

idleprocs=4 threads=9 idlethreads=2 runqueue=0 [0 0 0 0]

idleprocs=0 threads=5 idlethreads=0 runqueue=9 [4 0 3 0]

idleprocs=4 threads=9 idlethreads=2 runqueue=0 [0 0 0 0]

idleprocs=0 threads=5 idlethreads=0 runqueue=10 [2 1 1 2]

idleprocs=4 threads=9 idlethreads=2 runqueue=0 [0 0 0 0]

idleprocs=0 threads=5 idlethreads=0 runqueue=6 [2 1 0 0]

Thanks for reading my article about Go’s concurrency. I hope you could learn something new.

Cheers!