The following is a review of today’s massive source of information and how the hard part is to now find the right information to learn.

https://www.strangeloopcanon.com/p/discovery-is-the-original-sin-of

When I was in college, I got a letter from Columbia Tristar calling me a pirate. In better phrasing it said I, or rather my IP, had been downloading a movie via Kazaa and I shouldn’t do that because that’s illegal. They were right of course, and I listened to them and stopped immediately. After all, Bit Torrent was right there.

At this time along with bad movies I had pretty much most of the music I had ever heard of and ever would be able to hear on my hard drive. There was no streaming and the only way to sate my evanescent moods was to store the entirety of the world’s musical output locally.

But soon, iTunes started allowing you to purchase songs for 99 cents. Spotify started not long after, allowing me to stream music. No need to store anything anymore. The cost of me getting a piece of music from the cloud was so low that the very idea of piracy became quaint.

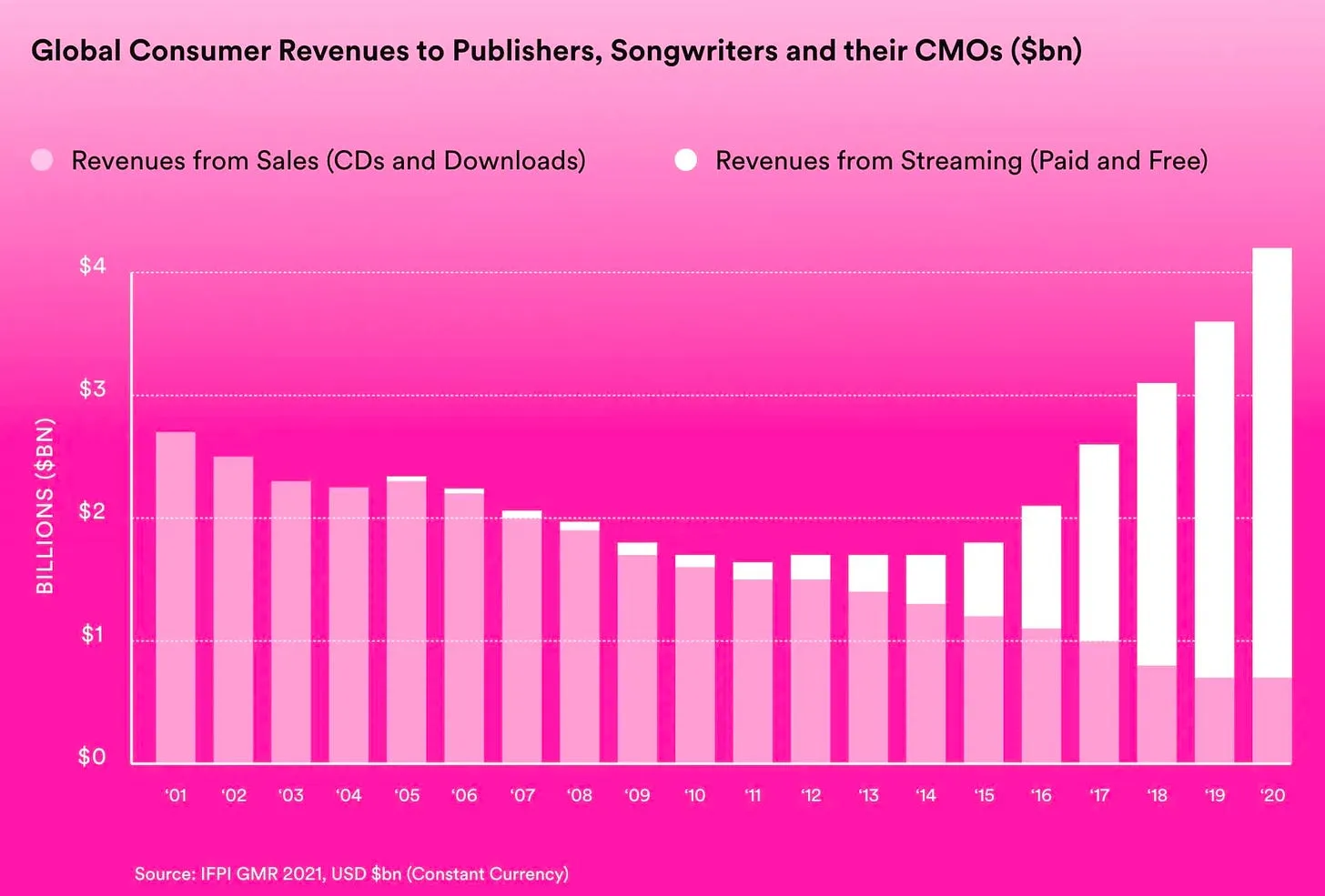

Today 200,000 professional or aspiring artists generate 95% of the royalty pool on Spotify. Around 3,000 of them made over $100,000 in 2022. They have, over the years, paid out around $40 billion to music rights holders.

While I wasn’t particularly discriminating, I didn’t have 200,000 artists’ music on my hard drive. I couldn’t.

There just weren’t that many artists I could know about!

If you’re a musician, you have been given a gift with streaming. An immediate, one step access to any listener anywhere in the world. Sans intermediaries.

If you’re a listener, you too have been given a gift. An incredible range of any type of music you could possibly have imagined, all at your fingertips.

But the gift comes with a curse. You have to find it. The proverbial needle in a haystack.

And how do you find that which you do not know to look for?

This is the original sin of modernity. We have cleared access, but at the cost of discovery.

It’s the same across every domain of facts or opinion or culture. We have more news than ever before, but it’s impossible to discover what is important without spending an enormous amount of time.

You could spend every second on Twitter and honestly be more informed about the world than most Presidents would have been a decade ago, but at the cost of spending every second on Twitter.

It’s the same for movies. Netflix and Prime and Disney and Hulu and Paramount and HBO and many many more, all compete to provide us with everything that humanity has ever created. If you can find it.

Substack, where you are reading this fine essay, is no different. They provide an abundance of essays, but at the cost of having to deal with that abundance.

And it’s not just movies or books or essays, it’s also true of everything where we’ve had abundance. Even finding a good restaurant or shampoo. Or sifting through twenty five types of tomato sauce.

Or looking at the hundreds of software vendors for almost any niche you can imagine. The meme about notetaking applications is true for a reason. There are hundreds of them, because we live in a time of plenty. It’s not just consumer apps either. I looked at Learning Management Systems at some point a few years ago, and found more than a thousand vendors! How would a company even choose which one to buy one of those?

Or when you think about buying a kitchen appliance? Or when you think about buying a TV? Or when you buy a music system? Or even a phone? Or a particular type of HDMI cable? Or cookware? Or the restaurant to eat out at tonight?

You rely on recommendations. You rely on brands. You rely on an authoritative “yes” from a trusted source. All to stave off the “fear of missing out”. All the more important because we drown in FOMO because the availability of hundreds of alternatives for anything means no search is optimal.

This by the way is why software is moving even more towards open source. It’s one way to demonstrate you are good, to give it away for free. Unfortunately it makes making money harder, but it works extraordinarily well as a resume stuffer.

A Red Hat survey says IT leaders are choosing to work with enterprise open source vendors, and 82% are more likely to select a vendor who contributes to the open source community.

And we have no choice but to continue to do this again and again, seemingly stuck in a Red Queen Race.

Until, that is, as

mentions in his essay, the methods of evaluating become a noose around our collective necks.

Today, your GitHub bathroom wall, your Kaggle ranking, and your Hugging Face leaderboard appearances can determine whether your resume will head to the bin or the hiring manager’s inbox.

We, collectively as a community, are forced to play these stupid RL career games because if you refuse, you become illegible and, consequently, invisible to sources of physical, emotional, and intellectual sustenance. It’s like we are all trapped in vicious cycles of RL career games while hoovering up others in these cycles.

Now, the traditional way to solve this has been through algorithms. We rely on them to find patterns in what you read or listened to or watched and then identify other things which you might like to read or listen to or watch.

It’s the secret behind the much maligned Facebook newsfeed. And pretty much any other digital media you have touched since the internet became a thing.

The other way to do this is to create a garden. Where you try and get the individual creators to recommend pieces to each other. This is a slightly more decentralised, but explicitly hierarchical, way to solve the problem.

This is how Substack recommendations work, for instance. And it works quite well.

The best in class is still the arenas where the platform is the true star, not the creator. Tiktok is the perfect case in point. You might become a Tiktok creator, but not so much that Tiktok does not remain the star in that equation. Discovery trumps creativity in the era of abundance.

Some of this is just mathematical. If there is any upper bound on our attention and judgement, as there clearly has to be, then even minimal levels of growing productivity would drown us in plenty.

At some point it was inevitable that we would have to contend with the ever increasing information overload and find ways to triage it so we could hold on to our semblance of sanity. It could only ever have been technological.

The only real solution I have found is to find taste makers. Those whom you can rely on to find the thing you want, to whom you can offload the responsibility to find things to your taste. Your aesthetic twin.

This is both non-scalable, my taste will differ from yours in slight but important ways, and also time consuming. This moves the question up one level - from “how do you find that piece of music” to “how do you find that person who will find that music”.

The fact that the second question is seeming more tractable than the first is also an example of the era of abundance we’re living in.

Relying on taste makers is hard. Choosing them, finding them, recognising them, that’s the job of a lifetime. Finding the contours of another’s tastes and abilities is difficult. There are no objective metrics, there are no quantitative measures. There’s only trial and error, waiting for that feeling when someone’s nous fits yours. And then hoping that it stays somewhat the same. Like the writers you got a little tired of reading regularly and then stopped following so rigorously over time.

Living in a world of plenty brings new problems which we might not have seen before. It means we have to create systems to deal with the large quantities that emerge. It means that our failures become the failure of system design, rather than the failures of individual lack of imagination.

And then the failures themselves get turned into mythical monsters that we attach to events. We can then get angry at Facebook’s impersonal algorithms instead of understanding that, as Ben Evans has written, the solution to plenty is to use something to help whittle it down.

Adam Mosseri talked about this when he discussed the Facebook News Feed.

(there’s) more and more information for us to consume every day, but only so much time we have in which to do that.

It worked great for them. From a Wired article, 10 years after it launched.

From the start, the News Feed’s central feature was that it didn’t show everything: it curated the information your friends posted to surface what was most relevant to you.

They were solving the problem of plenty.

If discovery truly is the original sin of the technology age, the solution too could only be technological. To find ways to somehow sift through the deluge of options to somehow choose one, or reduce the paradox of choice a tad.

Because the alternative is to vie for new forms of attention capture - like President Nixon visiting Hunan and regional food becoming popular. Similar to the Beatles visiting Rishikesh in 1968 or holding the FIFA world cup in South Africa in 2010. Just hoping that you can get a flashy high profile visit or rely on arbitrary major events to redirect attention.

It’s one way to solve the problem of plenty. Not the most scalable one however, nor particularly optimal.

Or there’s the Tyler Cowen theory of choosing a good restaurant being a full one which also has bad service and grumpy eaters, a clear indication that it’s been selected for food quality and not ambience, a private method to solve a discovery problem that has asymmetric payoffs, if you are Tyler.

Whatever the format, this is now a fact of our modern age. It’s what everyone has to focus on, whether they want to or not. It’s what causes the rise of the everlasting love towards zettelkasten and note taking and productivity apps, which tell us that if we just use it then we’ll capture the chaos and manage it. It’s the rise of influencer marketing. It’s why we love to hate the algos even as we can’t help but love them. It’s why we love listicles.

It’s why folks try and have scouts to find the companies that were overlooked as investors. It’s why competitor intelligence is now a full contact competitive sport. It’s why every job on LinkedIn has 300 applications and nobody can rise above the noise without knowing someone.

We need some way of navigating this, because total available information’s not going to go back down. It can’t be one size fits all, like an algo run by a service and nominally personalised. It has to be yours, capturing your idiosyncrasies and interests. It has to be local, it has to know you, and it has to be smart enough to navigate the world that’s thrown at it. There’s only one real answer.