The following is an explanation on an old method to quickly estimate the square root of a number in your brain. The algorithm explanation is really to understand and it gives the feeling of a math hack that we can use to enhance our thinking process. The remaining sections are more about technical math stuff which can be hard to understand.

https://gregorygundersen.com/blog/2023/02/01/estimating-square-roots/

Imagine we want to compute the square root of a number n. The basic idea of Heron’s method, named after the mathematician and engineer, Heron of Alexandria, is to find a number g that is close to n and to then average that with the number n/g, which corrects for the fact that g either over- or underestimates n.

I like this algorithm because it is simple and works surprisingly well. However, I first learned about it in (Benjamin & Shermer, 2006), which did not provide a particularly deep explanation or analysis for why this method works. The goal of this post is to better understand Heron’s method. How does it work? Why does it work? And how good are the estimates?

The algorithm

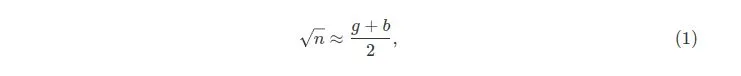

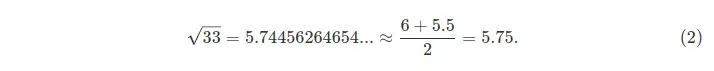

Let’s demonstrate the method with an example. Consider computing the square root of n=33. We start by finding a number that forms a perfect square that is close to 33. Here, let’s pick g=6, since 62=36. Then we compute a second number, b=n/g. In practice, computing b in your head may require an approximation. Here, we can compute it exactly as 33/6=5.5. Then our final guess is the average of these two numbers or

which in our example is

That is pretty good. The relative error is less than 0.1%! And furthermore, this is pretty straightforward to do in your head when n isn’t too large.

Why does this work?

Intuitively, Heron’s method works because g is either an over- or underestimate of n. Then n/g is an under- or overestimate, respectively, of n. So the average of g and n/g should be closer to n than either g or n/g is.

While this was probably Heron’s reasoning, we can offer a better explanation using calculus: Heron’s method works because we’re performing a second-order Taylor approximation around our initial guess. Put more specifically, we’re making a linear approximation of the nonlinear square root function at the point g2.

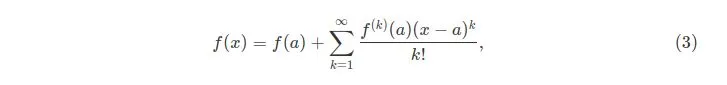

To see this, recall that the general form of a Taylor expansion about a point a is

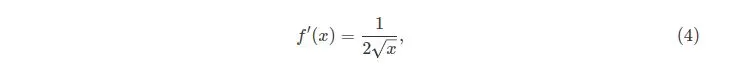

where the notation f(k) denotes the k-th derivative of f. If we define f(x)=x, then

and so the second-order Taylor approximation of x is

Now choose x=n, and let h(x) denote the Taylor expansion around a=g2. Then we have

And this is exactly what we calculated above.

Geometric interpretation

In general, the second second-order Taylor expansion approximates a possibly nonlinear function f(x) with a linear function at the point a:

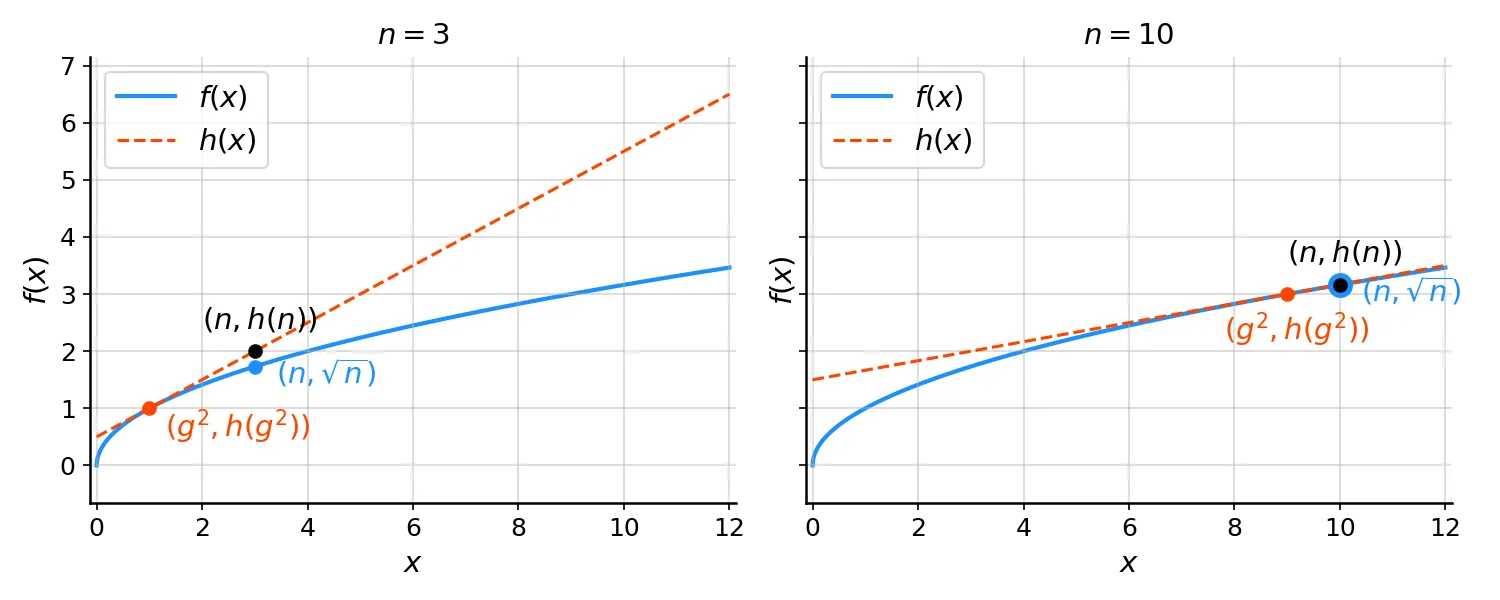

Thus, the Taylor approximation represents the tangent line to f(x) at the point (a,f(a)). We can see this for f(x)=x in Figure 1. This is a useful visualization because it highlights something interesting: we expect Heron’s approximation to be worse for smaller numbers. That’s because the square root function is “more curved” (speaking loosely) for numbers closer to zero (Figure 2, left). As the square root function flattens out for larger numbers, the linear approximation improves (Figure 2, right).

Figure 1. A visualization of Heron’s method, or a second-order Taylor approximation of f(x)=x. We construct a linear approximation h(x) (red dashed line) to the nonlinear function f(x) (blue line). We then guess h(n) (black dot). Our error is the absolute vertical difference between h(n) (black dot) and n (blue dot).

How good is the approximation?

How good is this method? Did we just get lucky with n=33 or does Heron’s method typically produce sensible estimates of n?

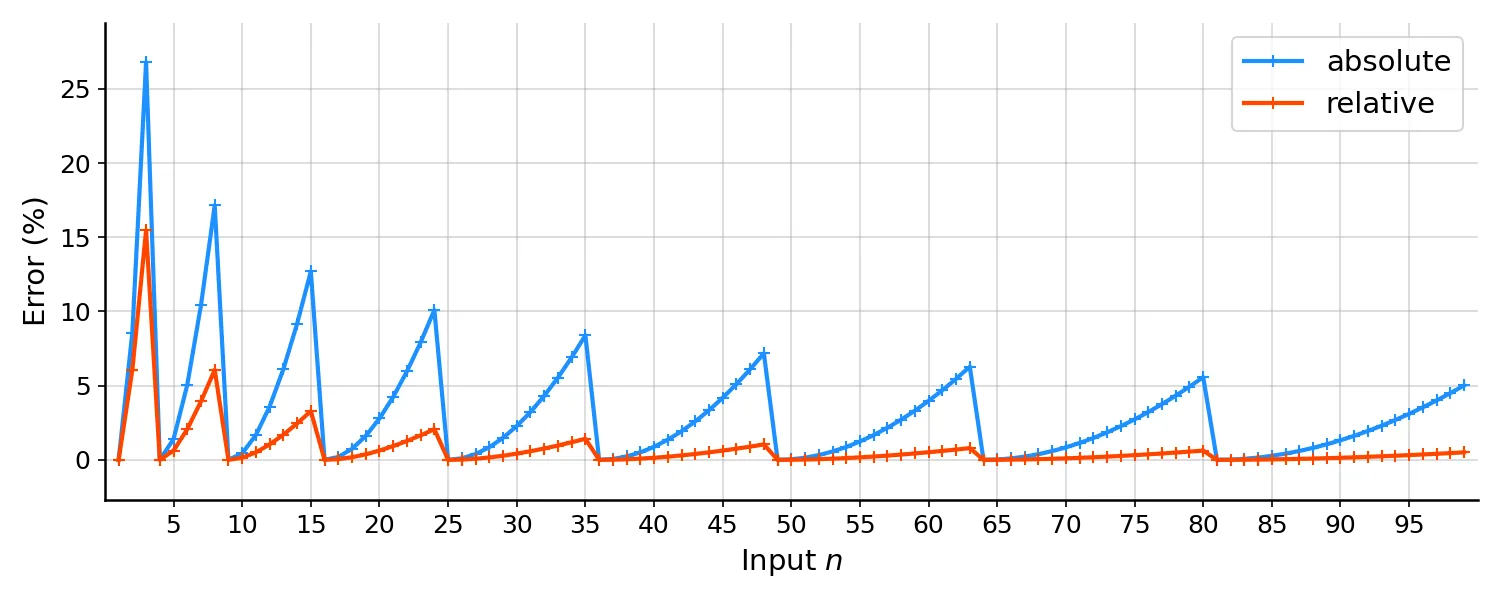

To answer this question, I’m replicating a nice figure from an article from MathemAfrica, in which the author makes a plot with the input number n on the x-axis and the absolute error

on the y-axis (Figure 2, blue line). (Note that when programming Heron’s method, we must decide if we want to find g2 by searching numbers greater or less than n; here, I’ve set g as the first integer less than the square root of n, or as g = floor(sqrt(n)).) I like this figure because it captures two interesting properties of Heron’s method. First, as we discussed above, the Taylor approximation will typically be worse when n is small (when f(x)=x; this is not true in general). And second, the error drops to zero on perfect squares and increases roughly linearly between perfect squares.

Figure 2. The absolute (blue) and relative (red) errors between the true value n and the estimate using Heron’s approximation h(n). The errors are zero when n is a perfect square and are smaller on average for small n than for large n.

The MathemAfrica post focuses on lowering this absolute error by judiciuosly picking the initial guess g. This is interesting as analysis. However, in my mind, this is unnecessarily complicated for most practical mental math scenarios, i.e. for quick sanity checking rather than in a demonstration or competition. Why it is overly complicated? Well, the relative error,

rapidly decays to less than a percentage point or so (Figure 2, red line).

If you’re not using a calculator to compute a square root, you’re probably just getting a rough idea of a problem. And if we actually wanted to lower the absolute error and didn’t care about a human’s mental limits, we should just expand the Taylor approximation to higher orders.