The following article touches on two different topics: the main one which is how the author and his team created an anti-corruption layer (wrapper) around the Android Gradle Plugin, and the offside one which involves philosophic points such as Nihilism, and politics.

https://dev.to/autonomousapps/nihilism-and-the-anti-corruption-layer-560n

Every now and then someone asks me if I intend a more technical follow-up to Herding Elephants, which was a fairly high-level overview of the strategy I initiated to modernize that large Android repo I help maintain. And the answer is—not really. It is hard to appreciate how many moving parts exist in a repo at that scale without seeing it for yourself. Many of the lessons learned are irrelevant for smaller projects, which is most of them. The solutions to these medium-large problems1 are expensive to build and expensive to maintain, and the cost-benefit analysis is only in their favor at a certain, well, scale. Dozens of developers and hundreds or thousands of modules. Millions of lines of code.

Of all the components that form part of our current build system, however, one stands out as particularly cool and also as a metaphor for the human condition, which is what I really want to talk about.

What to expect if you keep reading

I will elaborate on the anti-corruption layer I built to protect our build from upstream changes coming from the rapidly-evolving Android Gradle Plugin, and discuss how this has helped our build maintain stability and migrate to newer releases reliably and with increasing rapidity. I will wave my hands at some of the guard rails I built. I will discourage you from attempting this yourself. I will then pivot to how this relates to nihilism and the human condition.

The anti-corruption layer

As any Android developer with more than a year or two of experience knows, the Android Gradle Plugin (AGP) is constantly evolving. For the very simplest projects, these changes are largely transparent, but I would guess that most Android projects have had frustrations with these changes over the years.

One of the pain points of AGP is that its API is constantly changing. (Google even has a documented “migration timeline” for this API; it spans years.) Google also takes the idiosyncratic perspective that many of its public classes aren’t really public API, but internal implementation detail, and because of this, it often pushes breaking changes without any corresponding signal via semantic versioning.

There are two extreme solutions to this problem. At one extreme, which I highly recommend you follow, is being a Conformist. This is a design pattern whereby you essentially “give up” and admit that you will never really be able to craft a model specific to your project. Your model is AGP’s model. This is fine.

This is fine

At the other extreme we have the Anti-corruption layer. You probably shouldn’t do this.2

An anti-corruption layer is used when a downstream project has a dependency on an upstream that it (1) has no control over; (2) can’t avoid; and (3) doesn’t trust. This precisely describes our relationship with AGP. The concept is often summarized as “wrapping” dependencies, but it is more than that. Let’s consider the implementation of this pattern that we use in the “convention plugins” I wrote about in Herding elephants.

I want to be clear here that I’m speaking in a highly technical sense. I am not making normative judgments about AGP’s structure nor the direction of its evolution. In point of fact, I often have fruitful discussions with members of the team that maintains AGP, whom I like and respect. Nevertheless, the only power I hold over that upstream dependency is the power of persuasion, which doesn’t cut it when my code is used tens of thousands of times per day to build software that powers a multi-billion dollar business.

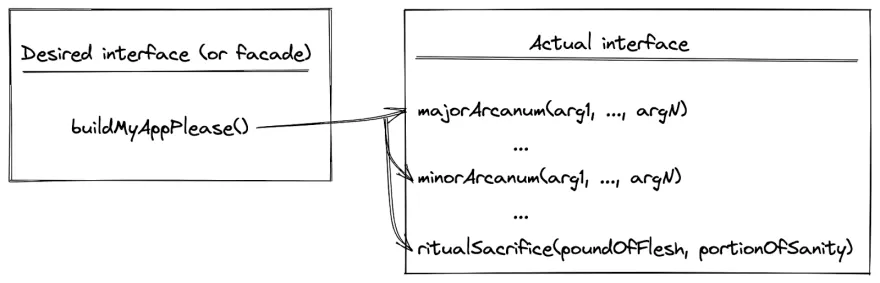

We start with the facade, or wrapper interface. A facade is the interface we wish we had, and which takes care to redirect to the actual interface provided by the dependency (AGP in this case). Here’s a simplified example:

Wrapper interface

On the right is AGP, which has complicated methods like majorArcanum(...) and minorArcanum(...), which each take many arguments. On the left we have our desired interface, which is just a single method that takes no arguments. We can do this because, while AGP is a general purpose build tool that has to solve problems for Every Android Developer Everywhere, we have a different, smaller problem: how to build our apps for our developers.

We wrap our facade in an “adapter” that knows how to talk to different versions of AGP. This is how we solve the problem of AGP’s rapidly changing interface. Our adapter can provide a different implementation for each version of AGP we support, which is the current version plus the next two release candidates in the AGP pipeline. Through this mechanism, we can update to each new release with ease—no more months-long migrations.

To help you visualize how this works, consider this simplified implementation:

class AndroidGradlePluginFactory(

private val project: Project,

private val agpVersion: AgpVersion,

) {

companion object {

fun getAdapter(project: Project): AndroidGradlePlugin {

return AndroidGradlePluginFactory(

project = project,

agpVersion = AgpVersion.current(project)

).newAdapter()

}

}

fun newAdapter(): AndroidGradlePlugin = when {

agpVersion >= AgpVersion.version("7.3") -> AndroidGradlePlugin7_3(project)

agpVersion >= AgpVersion.version("7.2") -> AndroidGradlePlugin7_2(project)

agpVersion >= AgpVersion.version("7.1") -> AndroidGradlePlugin7_1(project)

else -> throw UnknownAgpException("No adapter for AGP $agpVersion")

}

}

Enter fullscreen mode Exit fullscreen mode

Please be warned that AgpVersion.current(project) encapsulates a non-trivial implementation for retrieving the actual version of AGP that is present at runtime. Also note that each implementation is encapsulated in its own project (module) to isolate its classpath.

To use this factory, your plugins should look like this:

class MyPlugin : Plugin<Project> {

override fun apply(target: Project) {

val agp = AndroidGradlePluginFactory.getAdapter(target)

// all accesses of AGP functionality _must_ go through `agp`

}

}

Enter fullscreen mode Exit fullscreen mode

You can also inject an agp instance into your custom extension and then require your developers to use that extension (rather than the backing android extension) for customizing their projects.

abstract class CircleExtension(agp: AndroidGradlePlugin) {

fun buildMyAppPlease(how: String) { … }

}

Enter fullscreen mode Exit fullscreen mode

// app/build.gradle

plugins {

id 'com.circle.android.app'

}

circle {

buildMyAppPlease 'with style'

}

Enter fullscreen mode Exit fullscreen mode

Guard rails

This is already pretty complicated, yet it’s also not enough. This is why you shouldn’t do it. But if you insist, below are some of the guards we’ve had to institute to keep from going off the rails.

Please note that, in each case, I’m dramatically simplifying our build setup so that it fits into a blog post shorter than a master’s thesis. This isn’t easy and you should think long and hard before deciding to do this.

Comprehensive test suite

All of our plugins are thoroughly tested against all supported versions of AGP. This is very hard to get right, but utterly necessary.

NoAgpAtRuntime

We have a task, noAgpAtRuntime, that is registered on all of our build-logic modules. This task will fail if it discovers a class from AGP on the build classpath. We expect the build that applies our plugins (the “main build”) to be responsible for providing AGP.

Strict dependencies

We set a strict dependency constraint on our root build classpath to ensure it’s using the version of AGP we specify for every build.

// root build.gradle of main build

buildscript {

dependencies {

constraints {

classpath('com.android.tools.build:gradle') {

version { strictly agpVersion /* a string */ }

}

}

}

}

Enter fullscreen mode Exit fullscreen mode

DependencyGuard

We use DependencyGuard to fail our build if the build classpath changes unexpectedly.

// root build.gradle

plugins {

id 'com.dropbox.dependency-guard'

}

dependencyGuard {

configuration('classpath')

}

Enter fullscreen mode Exit fullscreen mode

Nihilism gets a bad rap

What has any of this to do with nihilism?3 As a concept, it’s something I’ve been flirting with my entire life, and it came to a head recently when I happened to catch an episode of Radiolab from 2014, about a book called “In the Dust of This Planet”—a book I subsequently bought and devoured.

I think most people have weird ideas about what nihilism means; my first encounter with it was probably when I saw The Big Lebowski as a teenager.

Nihilists in The Big Lebowski

This is not the kind of nihilism I’m talking about. I mean it as more of a renunciation of received truth. In the context of software development, we have lots of received truths, and simply accepting them as such leads to the conformist approach (or “pattern”) discussed above. Rejecting those truths and going your own way contains, for me, an element of nihilism that I find myself embracing.

Nothing matters, so do what you want

I was already working on this post when I finally saw Everything Everywhere All at Once the other day. That movie is profoundly nihilistic and I <3 it so much. The primary antagonist in the film, Jobu Tupaki, has come to realize that nothing matters and so has created the everything-bagel-of-nothing, a thing which annihilates all who gaze upon it; this self-destruction is what she herself seeks. Her mother, Evelyn, comes to the same realization, but lands on a different conclusion, which is that, because nothing matters, she can do what she wants, and what she wants is to spend her one life with her loved ones.

One of the ways I know that nothing matters is that we’ve radically destabilized the climate such that it is a foregone conclusion that billions will die and civilizations will fall, and the present mass extinction will continue. We’re far too late to stop it, and this against a background of the majority of people wanting to stop it, but our public institutions being so corrupt that we can only watch in horror as they go in the opposite direction. Truly, “nothing matters.”

I guess you could say I’m an eco-nihilist.

On a day like today, I must also point out that the US Supreme Court, in an act of destructive nihilism, has further proven my point by going against the democratic majority to expand gun rights and constrict women’s rights, and is almost certainly setting up to further curtail personal liberty with attacks on LGBTQ rights in the coming years.

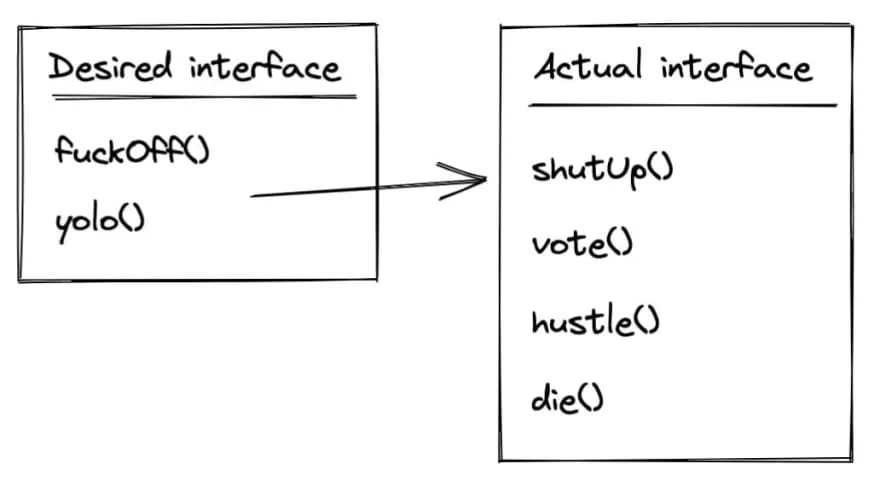

The anti-corruption layer, take 2

If you’ve read this far, you have the patience of a saint, and so I’m going to cut to the chase. My anti-corruption layer, that lets me continue to persist despite knowing, to my core, that nothing matters, is a deep well of incandescent rage. Conformity would be so much easier—it’s what practically everyone around me wants me to do. But I find it literally impossible. We live on a garden world in an endlessly empty universe; it could be a paradise yet we’ve built a death machine instead. I am so angry. That anger is my shield, but increasingly my nihilism is my shield, too. Nothing matters, so I’m going to do what I want.

An updated wrapper interface, this time around The World

Endnotes

1 We’re not truly large (cf Google). up

2 The world of software development is thick with metaphor. This post uses numerous metaphors from the world of design patterns, with a focus on two in particular: Conformist and Anti-corruption layer. I learned the names of these patterns from the book Domain-driven design by Eric Evans, but discovered them independently through an intent focus on solving the kinds of problems I often write about on this blog. See also Christopher Alexander and A Pattern Language. up

3 I am not a philosopher (IANAP). up

#reads #architecture #gradle #android #software #anti corruption layer #nihilism