The author does a breakdown on current metrics for what people consider a strong password and goes on to explain that these methods are flawed, proving his theory with math. In the end he explains that a strong password shouldn’t be a password that is hard to remember, but instead should have higher entropy/characters, so that computing its hash version is significantly harder.

The method he presents to create a strong password is to create a passphrase that can be easy to remember, but has an higher entropy as more words are chosen. Well, mathematically speaking and considering the whole domain of available words, computing a password that is composed by 6 of them is really hard. But I think we shouldn’t just consider this estimation as a silver-bullet metric: what if the attacker knows the words dictionary before hand, and thus knows the domain and method chosen to create a password?

https://palant.info/2023/01/30/password-strength-explained

The conclusion of my blog posts on the LastPass breach and on Bitwarden’s design flaws is invariably: a strong master password is important. This is especially the case if you are a target somebody would throw considerable resources at. But everyone else might still get targeted due to flaws like password managers failing to keep everyone on current security settings.

There is lots of confusion about what constitutes a strong password however. How strong is my current password? Also, how strong is strong enough? These questions don’t have easy answers. I’ll try my best to explain however.

If you are only here for recommendations on finding a good password, feel free to skip ahead to the Choosing a truly strong password section.

Contents

- Where strong passwords are crucial

- How password guessing works

- The mathematics of guessing passwords

- Estimating the complexity of a given password

- How strong are real passwords?

- Choosing a truly strong password

Where strong passwords are crucial

First of all, password strength isn’t always important. If your password is stolen as clear text via a phishing attack or a compromised web server, a strong password won’t help you at all.

In order to reduce the damage from such attacks, it’s way more important that you do not reuse passwords – each web service should have its own unique password. If your login credentials for one web service get into the wrong hands, these shouldn’t be usable to compromise all your other accounts e.g. by means of credential stuffing. And since you cannot possibly keep hundreds of unique passwords in your head, using a password manager (which can be the one built into your browser) is essential.

But this password manager becomes a single point of failure. Especially if you upload the password manager data to the web, be it to sync it between multiple devices or simply as a backup, there is always a chance that this data is stolen.

Of course, each password manager vendor will tell you that all the data is safely encrypted. And that you are the only one who can possibly decrypt it. Sometimes this is true. Often enough this is a lie however. And the truth is rather: nobody can decrypt your data as long as they are unable to guess your master password.

So that one password needs to be very hard to guess. A strong password.

Oh, and don’t forget enabling Multi-factor authentication (MFA) where possible regardless.

How password guessing works

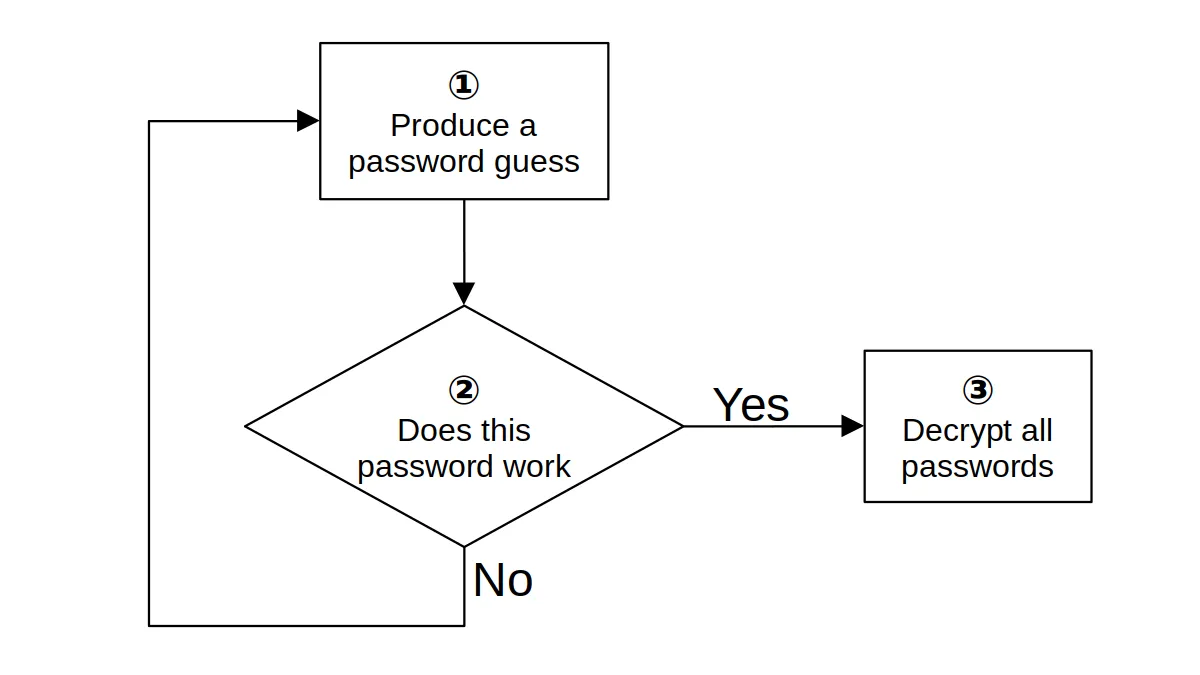

When someone has your encrypted data, guessing the password it is encrypted with is a fairly straightforward process.

Ideally, your password manager made step 2 in the diagram above very slow. The recommendation for encryption is allowing at most 1,000 guesses per second on common hardware. This renders guessing passwords slow and expensive. Few password managers actually match this requirement however.

But password guesses will not be generated randomly. Passwords known to be commonly chosen like “Password1” or “Qwerty123” will be tested among the first ones. No amount of slowing down the guessing will prevent decryption of data if such an easy to guess password is used.

So the goal of choosing a strong password isn’t choosing a password including as many character classes as possible. It isn’t making the password look complex either. No, making it very long also won’t necessarily help. What matters is that this particular password comes up as far down as possible in the list of guesses.

The mathematics of guessing passwords

A starting point for password guessing are always passwords known from previous data leaks. For example, security professionals often refer to rockyou.txt: a list with 14 million passwords leaked 2009 in the RockYou breach.

If your password is somewhere on this list, even at 1,000 guesses per second it will take at most 14,000 seconds (less than 4 hours) to find your password. This isn’t exactly a long time, and that’s already assuming that your password manager vendor has done their homework. As past experience shows, this isn’t an assumption to be relied on.

Since we are talking about computers here, the “proper” way to express large numbers is via powers of two. So we say: a password on the RockYou list has less than 24 bits of entropy, meaning that it will definitely be found after 224 (16,777,216) guesses. Each bit of entropy added to the password results in twice the guessing time.

But obviously the RockYou passwords are too primitive. Many of them wouldn’t even be accepted by a modern password manager. What about using a phrase from a song? Shouldn’t it be hard to guess because of its length already?

Somebody calculated (and likely overestimated) the number of available song phrases as 15 billion, so we are talking about at most 34 bits of entropy. This appears to raise the password guessing time to half a year.

Except: the song phrase you are going to choose won’t actually be at the bottom of any list. That’s already because you don’t know all the 30 million songs out there. You only know the reasonably popular ones. In the end it’s only a few thousand songs you might reasonably choose, and your date of birth might help narrow down the selection. Each song has merely a few dozen phrases that you might pick. You are lucky if you get to 20 bits of entropy this way.

Estimating the complexity of a given password

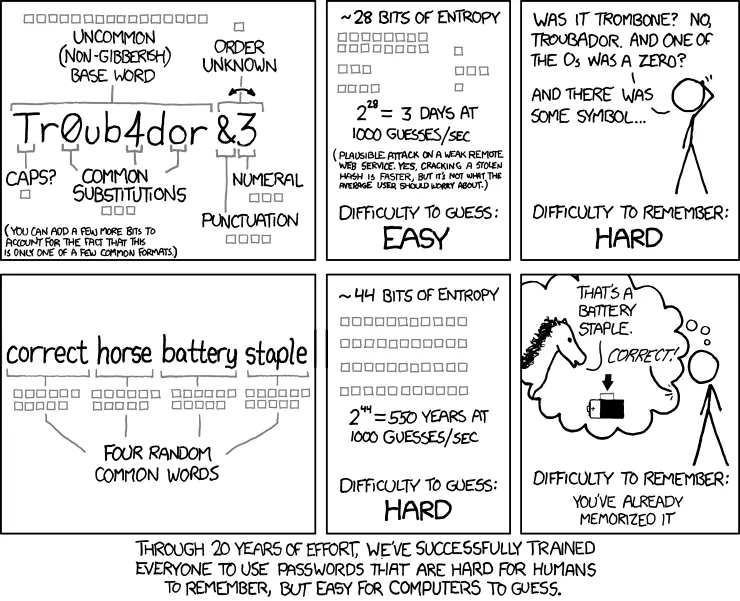

Now it’s hard to tell how quickly real password crackers will narrow down on a particular password. One can look at all the patterns however that went into a particular password and estimate how many bits these contribute to the result. Consider this XKCD comic:

Source: XKCD 936

An uncommon base word chosen from a dictionary with approximately 50,000 words contributes 16 bits. The capitalization at the beginning of the word on the other hand contributes only one bit because there are only two options: capitalizing or not capitalizing. There are common substitutions and some junk added at the end contributing a few more bits. But the end result are rather unimpressive 28 bits, maybe a few more because the password creation scheme has to be guessed as well. So this is a password looking complex, it isn’t actually strong however.

The (unmaintained) zxcvbn library tries to automate this process. You can try it out on a webpage, it runs entirely in the browser and doesn’t upload your password anywhere. The guesses_log10 value in the result can be converted to bits: divide through 3 and multiply with 10.

For Tr0ub4dor&3 it shows guesses_log10 as 11. Calculating 11 ÷ 3 × 10 gives us approximately 36 bits.

Note that zxcvbn is likely to overestimate password complexity, like it happened here. While this library knows some common passwords, it knows too few. And while it recognizes some English words, it won’t recognize some of the common word modifications. You cannot count on real password crackers being similarly unsophisticated.

How strong are real passwords?

So far we’ve only seen password creation approaches that max out at approximately 35 bits of entropy. My guess it that this is in fact the limit for almost any human-chosen password. Unfortunately, at this point it is only my guess. There isn’t a whole lot of information to either support or disprove it.

For example, Microsoft published a large-scale passwords study in 2007 that arrives on the average (not maximum) password strength being 40 bits. However, this study is methodically flawed and wildly overestimates password strength. In 2007 neither XKCD comic 936 nor zxcvbn existed. So the researchers calculate password strength by looking at the character classes used. Going by their method, “Password1!” is a perfect password, whooping 63 bit strong. The zxcvbn estimate for the same password is merely 14 bits.

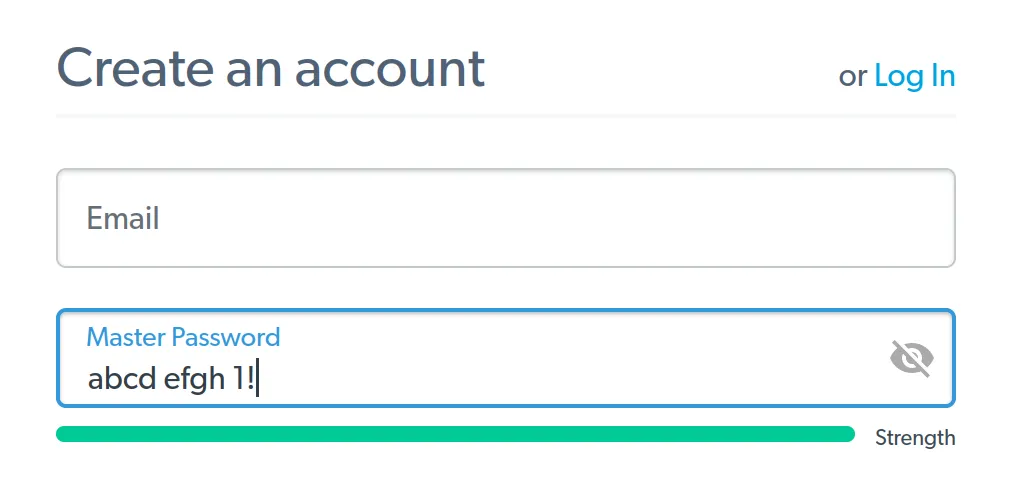

Another data point is the password strength indicator used for example on LastPass and Bitwarden registration pages. How strong are the passwords at the maximum strength?

Turns out, both these password managers use zxcvbn on their registration pages. And both will display a full strength bar for the maximum zxcvbn score: 4 out of 4. Which is assigned to any password that zxcvbn considers stronger than 33 bits.

Finally, there is another factor to consider: we aren’t very good at remembering complex passwords. A study from 2014 concluded that humans are capable of remembering passwords with 56 bits of entropy via a method the researchers called “spaced repetition.” Even using their method, half of the participants needed more than 35 login attempts in order to learn this password.

Given this, it’s reasonable to assume that in reality most people choose considerably weaker passwords: passwords that are still shown as “strong” by their password manager’s registration page, and that they can remember without a week of exercises.

Choosing a truly strong password

As I mentioned already, we are terrible at choosing strong passwords. The only realistic way to get a strong password is having it generated randomly.

But we are also very bad at remembering some gibberish mix of letters and digits. Which brings us to passphrases: sequences of multiple random words, much easier to remember at the same strength.

A typical way to generate such a passphrase would be diceware. You could use the EFF word list for five dice for example. Either use real dice or a website that will roll some fake dice for you.

Let’s say the result is ⚄⚀⚂⚅⚀. You look up 51361 in the dictionary and get “renovate.” This is the first word of your passphrase. Repeat the process to get the necessary number of words.

Update (2023-01-31): If you want it more comfortable, the Bitwarden password generator will do all the work for you while using the same EFF word list (type has to be set to “passphrase”).

How many words do you need? As a “regular nobody,” you can probably feel confident if guessing your password takes a century on common hardware. While not impossible, decrypting your passwords will simply cost too much even on future hardware and won’t be worth it. Even if your password manager doesn’t protect you well and allows 1,000,000 guesses per second, a passphrase consisting out of four words (51 bits of entropy) should be sufficient.

Maybe you are a valuable target however. If you hold the keys to lots of money or some valuable secrets, someone might decide to use more hardware for you specifically. You probably want to use at least five words then (64 bits of entropy). Even at a much higher rate of 1,000,000,000 guesses per second, guessing your password will take 900 years.

Finally, you may be someone of interest to a state-level actor. If you are an important politician, an opposition figure or a dissident of some kind, some unfriendly country might decide to invest lots of money in order to gain access to your data. A six words password (77 bits of entropy) should be out of reach even to those actors for the foreseeable future.