The following is an analysis of the migration from a microservice/serverless to a monolith architecture, for a media stream application on Amazon Prime Video. Initially, the team at Amazon designed the architecture to scale each component independently, but it turned out to be a money nightmare for Amazon, since all the scaling resulted in expensive bills.

One thing to remind when designing an application is to deeply evaluate what’s better: a monolith or microservices architecture. And this design must come not only through functional requirements (use cases), as well as non functional requirements (quality attributes), concerns and constraints (a good approach for this is the ADD methodology).

Clearly in this case, the domain wasn’t explored enough: how does it make sense to distribute a streaming application processing in different components, when it will involve one network request per video frame?

At Prime Video, we offer thousands of live streams to our customers. To ensure that customers seamlessly receive content, Prime Video set up a tool to monitor every stream viewed by customers. This tool allows us to automatically identify perceptual quality issues (for example, block corruption or audio/video sync problems) and trigger a process to fix them.

Our Video Quality Analysis (VQA) team at Prime Video already owned a tool for audio/video quality inspection, but we never intended nor designed it to run at high scale (our target was to monitor thousands of concurrent streams and grow that number over time). While onboarding more streams to the service, we noticed that running the infrastructure at a high scale was very expensive. We also noticed scaling bottlenecks that prevented us from monitoring thousands of streams. So, we took a step back and revisited the architecture of the existing service, focusing on the cost and scaling bottlenecks.

The initial version of our service consisted of distributed components that were orchestrated by AWS Step Functions. The two most expensive operations in terms of cost were the orchestration workflow and when data passed between distributed components. To address this, we moved all components into a single process to keep the data transfer within the process memory, which also simplified the orchestration logic. Because we compiled all the operations into a single process, we could rely on scalable Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2) and Amazon Elastic Container Service (Amazon ECS) instances for the deployment.

Distributed systems overhead

Our service consists of three major components. The media converter converts input audio/video streams to frames or decrypted audio buffers that are sent to detectors. Defect detectors execute algorithms that analyze frames and audio buffers in real-time looking for defects (such as video freeze, block corruption, or audio/video synchronization problems) and send real-time notifications whenever a defect is found. For more information about this topic, see our How Prime Video uses machine learning to ensure video quality article. The third component provides orchestration that controls the flow in the service.

We designed our initial solution as a distributed system using serverless components (for example, AWS Step Functions or AWS Lambda), which was a good choice for building the service quickly. In theory, this would allow us to scale each service component independently. However, the way we used some components caused us to hit a hard scaling limit at around 5% of the expected load. Also, the overall cost of all the building blocks was too high to accept the solution at a large scale.

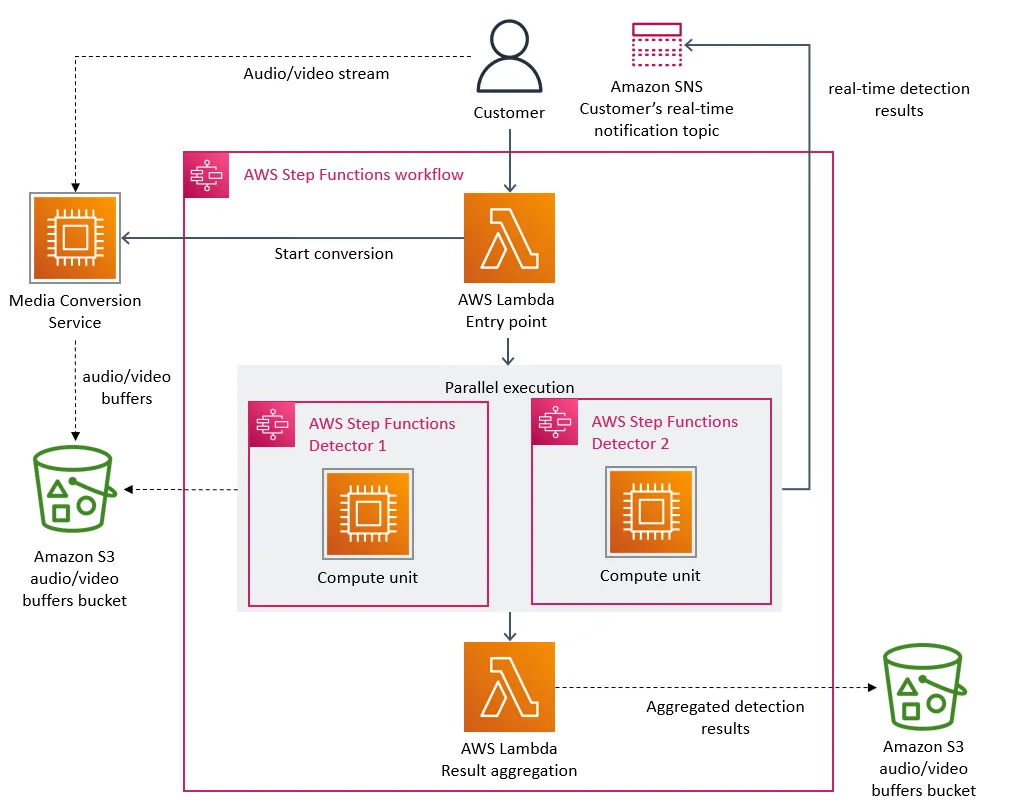

The following diagram shows the serverless architecture of our service.

The initial architecture of our defect detection system.

The main scaling bottleneck in the architecture was the orchestration management that was implemented using AWS Step Functions. Our service performed multiple state transitions for every second of the stream, so we quickly reached account limits. Besides that, AWS Step Functions charges users per state transition.

The second cost problem we discovered was about the way we were passing video frames (images) around different components. To reduce computationally expensive video conversion jobs, we built a microservice that splits videos into frames and temporarily uploads images to an Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3) bucket. Defect detectors (where each of them also runs as a separate microservice) then download images and processed it concurrently using AWS Lambda. However, the high number of Tier-1 calls to the S3 bucket was expensive.

From distributed microservices to a monolith application

To address the bottlenecks, we initially considered fixing problems separately to reduce cost and increase scaling capabilities. We experimented and took a bold decision: we decided to rearchitect our infrastructure.

We realized that distributed approach wasn’t bringing a lot of benefits in our specific use case, so we packed all of the components into a single process. This eliminated the need for the S3 bucket as the intermediate storage for video frames because our data transfer now happened in the memory. We also implemented orchestration that controls components within a single instance.

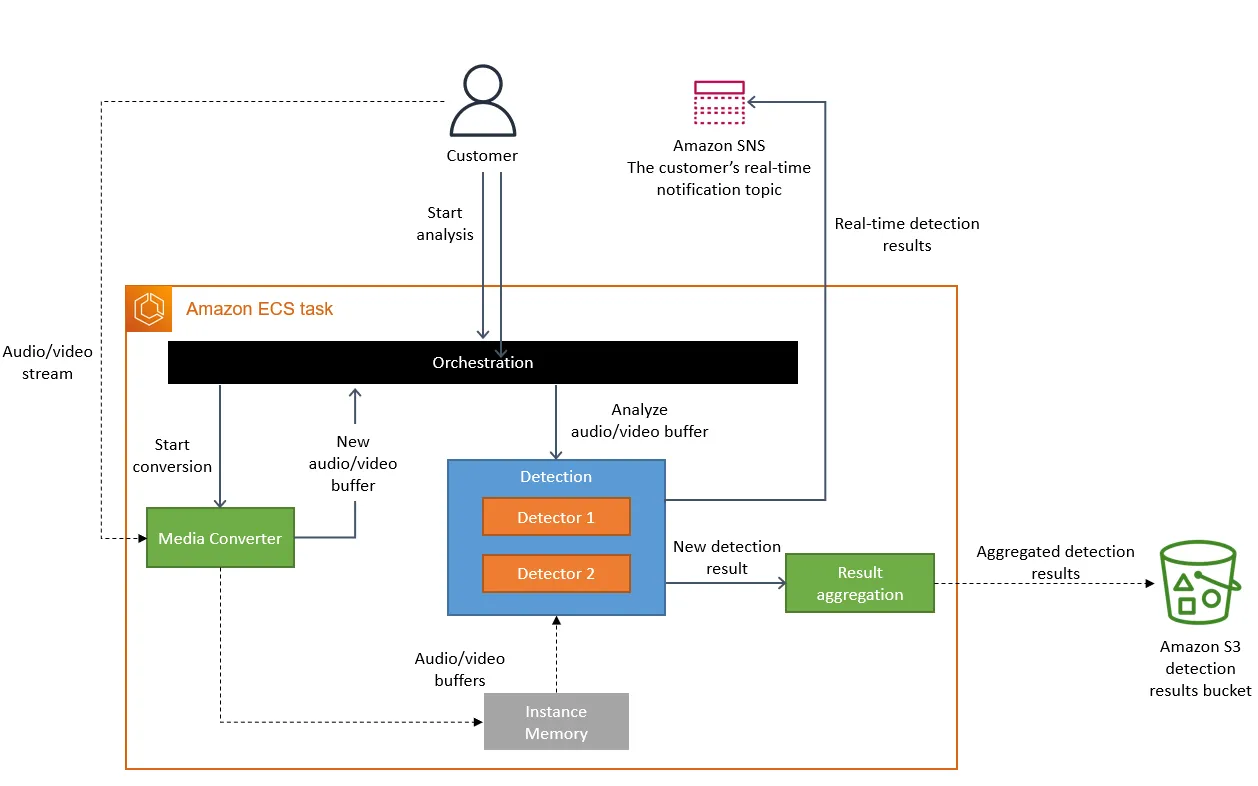

The following diagram shows the architecture of the system after migrating to the monolith.

The updated architecture for monitoring a system with all components running inside a single Amazon ECS task.

Conceptually, the high-level architecture remained the same. We still have exactly the same components as we had in the initial design (media conversion, detectors, or orchestration). This allowed us to reuse a lot of code and quickly migrate to a new architecture.

In the initial design, we could scale several detectors horizontally, as each of them ran as a separate microservice (so adding a new detector required creating a new microservice and plug it in to the orchestration). However, in our new approach the number of detectors only scale vertically because they all run within the same instance. Our team regularly adds more detectors to the service and we already exceeded the capacity of a single instance. To overcome this problem, we cloned the service multiple times, parametrizing each copy with a different subset of detectors. We also implemented a lightweight orchestration layer to distribute customer requests.

The following diagram shows our solution for deploying detectors when the capacity of a single instance is exceeded.

Our approach for deploying more detectors to the service.

Results and takeaways

Microservices and serverless components are tools that do work at high scale, but whether to use them over monolith has to be made on a case-by-case basis.

Moving our service to a monolith reduced our infrastructure cost by over 90%. It also increased our scaling capabilities. Today, we’re able to handle thousands of streams and we still have capacity to scale the service even further. Moving the solution to Amazon EC2 and Amazon ECS also allowed us to use the Amazon EC2 compute saving plans that will help drive costs down even further.

Some decisions we’ve taken are not obvious but they resulted in significant improvements. For example, we replicated a computationally expensive media conversion process and placed it closer to the detectors. Whereas running media conversion once and caching its outcome might be considered to be a cheaper option, we found this not be a cost-effective approach.

The changes we’ve made allow Prime Video to monitor all streams viewed by our customers and not just the ones with the highest number of viewers. This approach results in even higher quality and an even better customer experience.

#reads #amazon #microservices #serverless #distributed services #monolith #streaming