The following articles explains the problem of data consistency and replication when deploying instances on the edge.

https://zknill.io/posts/edge-database/

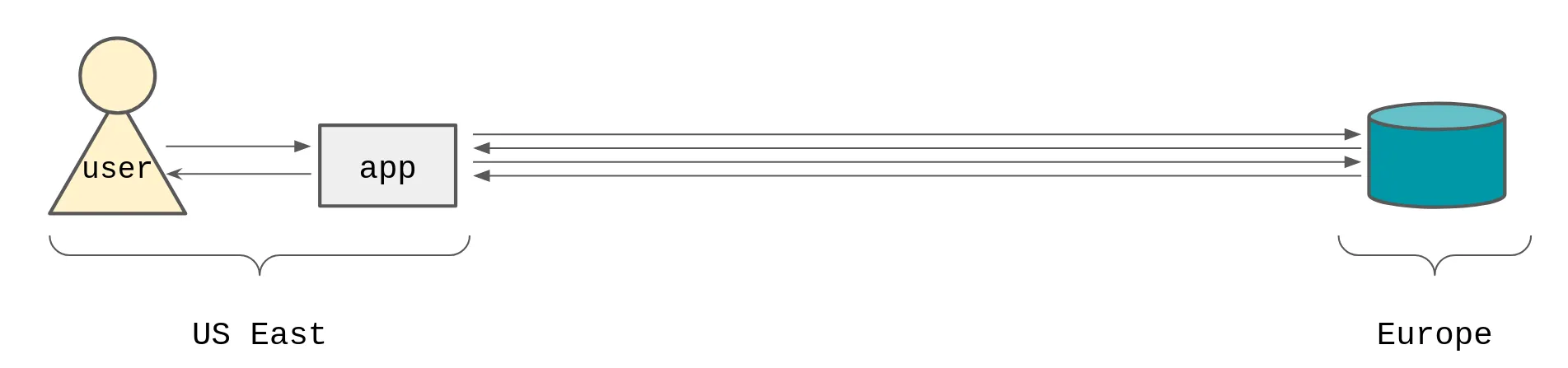

Application developers often deploy their apps into a single area, generally represented by a handful of AZs in a single region. No matter where their users make requests from, those requests get served by the region where the developers’ apps run.

If a user makes a request from Europe, and the apps run in US East, that adds an extra 100-150ms of latency just by round-tripping across the Atlantic.

Edge computing tries to solve this problem, by letting app developers deploy their applications across the globe, so that apps serve the user requests closer to the user. This removes a lot of the round-trip latency because the request has to travel less far before getting to a data center that hosts the app.

Edge computing sounds great for reducing response times for users, but the main thing stopping developers from adopting edge computing is data consistency.

Latency to the database

Apps generally make lots of database requests for a single user request

Apps often make lots of requests to the database for a single request from the user. So the cumulative latency becomes much higher because the request/response time includes the higher latency cost multiple times.

|Request|Time|Multiplier|Total| |user to app|20ms|1x|20ms| |app to db|150ms|2x|300ms| |-|-|-|320ms|

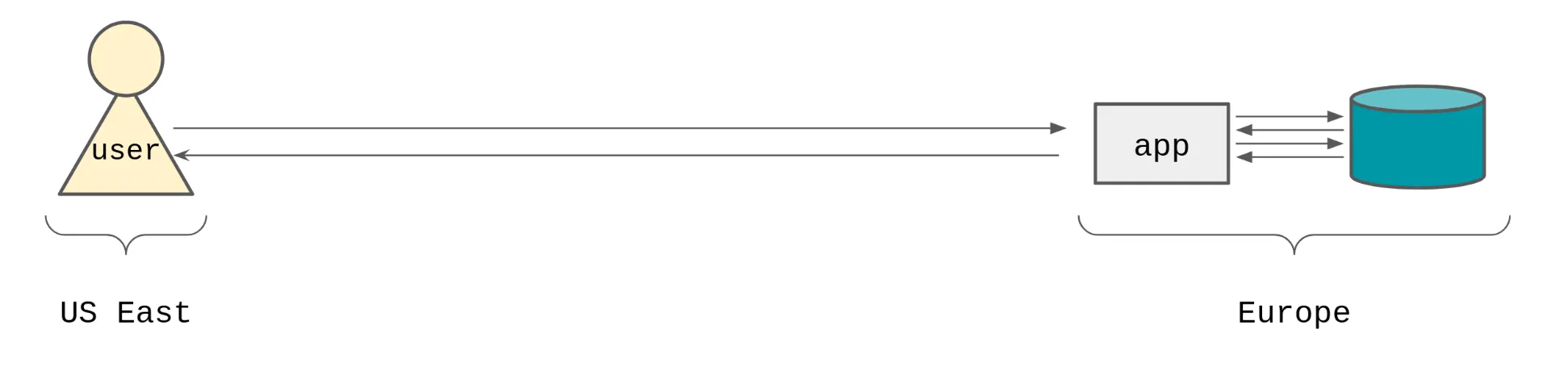

If the app is making multiple requests to the database for a single user request, then it makes sense to put the app and the database as close together as possible to minimise this app to db latency.

App close to the database to reduce the overall latency

|Request|Time|Multiplier|Total| |user to app|150ms|1x|150ms| |app to db|20ms|2x|40ms| |-|-|-|190ms|

By keeping the app and database close together, we can reduce the total response time for the user by 40%.

Edge computing and latency

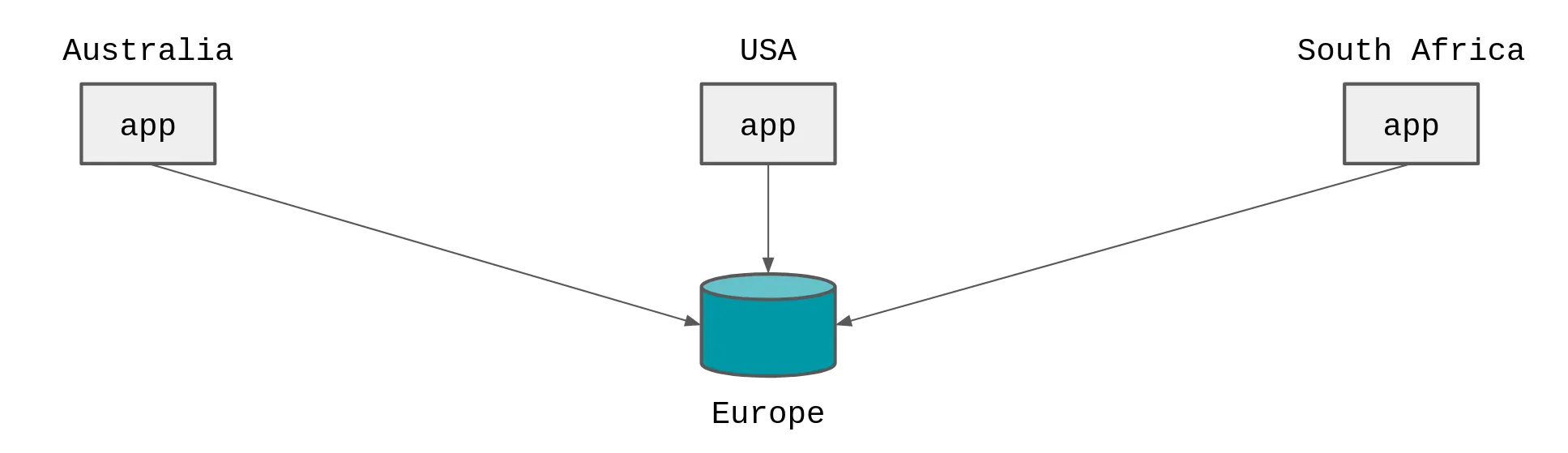

Edge apps with centralised database

Edge computing encourages you to run your apps closer to where the users are making requests from, under the premise that running closer to the users produces faster response times.

But as we’ve seen, the responses times for lots of round trips to a centralised database are slower than if the app was deployed near to the database.

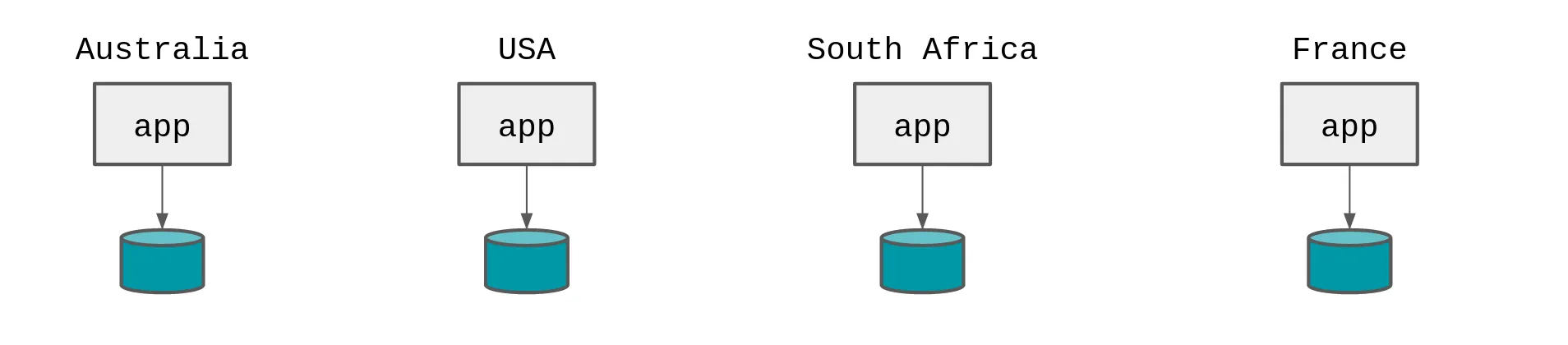

Logically the next step is to get a copy of your data as close to all the edge locations as possible.

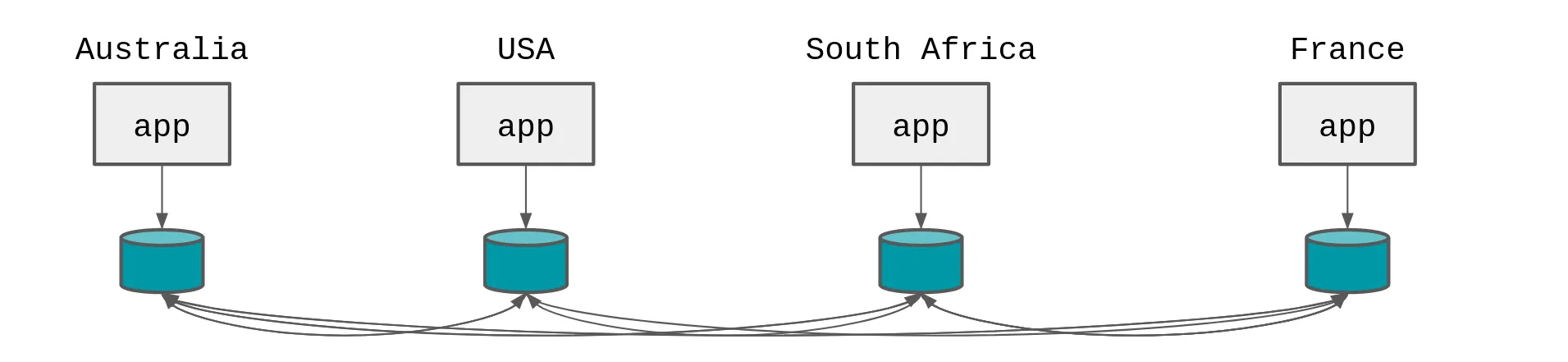

Edge apps with distributed databases

Data consistency

Imagine a new user signs up to your app. All users need a unique username because that’s how your app identifies them: how do you make sure the username is unique across all the copies of your data running on the edge?

We are left with the problem that: the main blocker to developers adopting edge computing is data consistency.

You need some way of checking that the username the user is registering with is unique. The only safe way to do that is to ask/be told by the other copies of the data if that username is unique or not. But to consult all the other copies of the data, we’d need to contact them. To contact the other copies of the data we will encounter the same cross-region latency that we suffered from when we had the database in a single location.

Cross region database latency

Two choices

If we want to maintain a copy of the data close to the edge app, and by extension close to the user, and if we want the data to be consistent, we have to deal with the cross region latency at some point.

The two choices we have boil down to; when do we want to deal with the cross-region latency required to make the data consistent?

- On writes – we can choose to contact the other copies of the data when writing a record, to make sure that no other users have already registered that username.

- On reads – we can choose to handle the data consistency problems on reads.

Strictly, we can choose to do both, because my usage of “consistent” so far in this post is quite vague, but we will come to that in a moment.

Lets start with writes. We know that we can’t have two users with the same username.

- Best case; the username isn’t taken,

- Middle case; the username is taken,

- Worst case; the username is being registered just as we are trying to register the username.

Best and middle cases are quite similar, we just need to know if the username is taken or not. The worst case is a little harder, because in this example we have two competing requests that are racing to register the username. We need a way to decide which one will (and did) win.

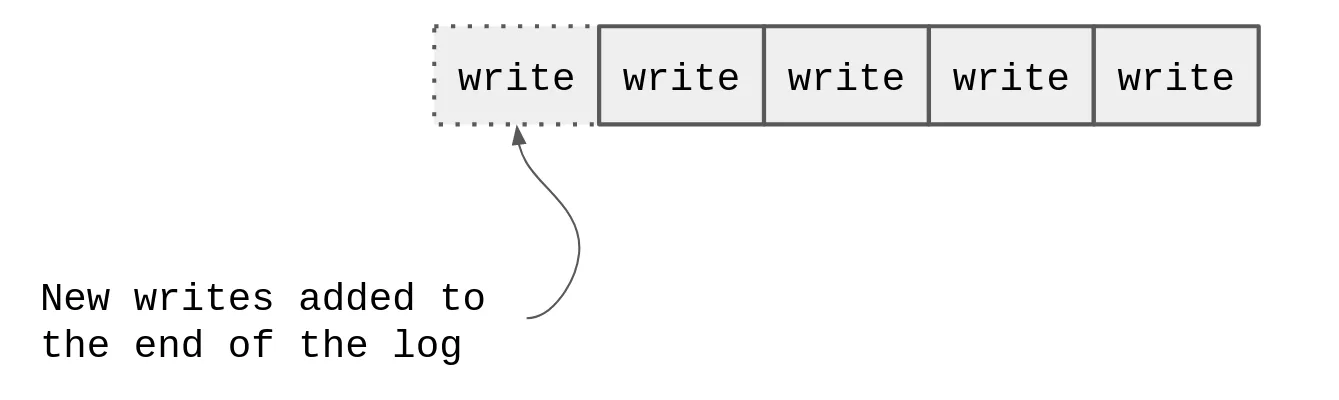

Append-only logs

Pretty much all databases solve the problem of two competing requests with an append-only log. Often called a Write-ahead log or WAL. Even if the database consists of only a single database server, the database still has to manage conflicting concurrent requests, and will still use a log.

These logs are append only - that is the database can only write to them - individual log events cannot be deleted. (Although outdated records in the log can be trimmed as a whole.)

The database has exactly one writer to the log, and when our two competing requests try and “write” (register the username), exactly one of those requests will be first, and the second will be rejected.

Append only log

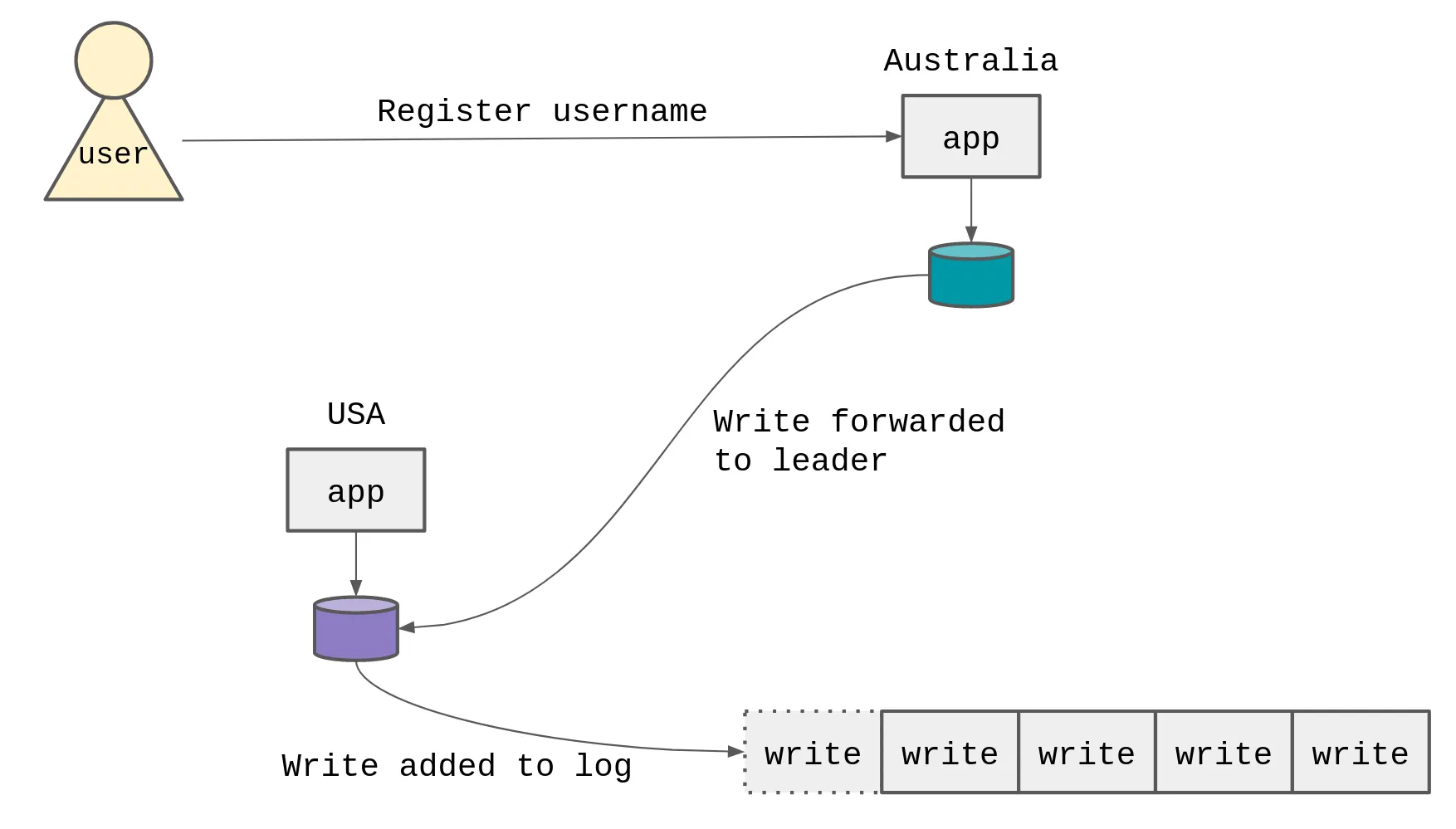

To guarantee that there’s exactly one writer to the log that our ‘register username’ write will go into, we need one database server to be responsible for that log. This database server called the “leader” or “master”.

Write forwarding

In this diagram, the user is registering a username. The database in Australia is forwarding the write to the database in the USA. The database in the USA is the ’leader’ for the username’s log, and writes the username to the log. The username is now ’taken’, and can’t be registered by anyone else.

We are dealing with the cross-region latency between Australia and USA when the write happens, to make sure that the data is consistent. (To make sure that no two users can register the same username).

The problem is that the write is now in the USA database, but not in the Australia database. If the user were to immediately make a request for their username, it wouldn’t exist in the Australia database (yet).

This property of the system / database (or lack of) is called read-your-own-writes. And describes a system where some data is available to be read immediately after its been written. Not being able to read your own writes creates a weird user experience, where the user is unsure if they have actually completed the task they wanted to, because they can’t immediately see the data they have just written.

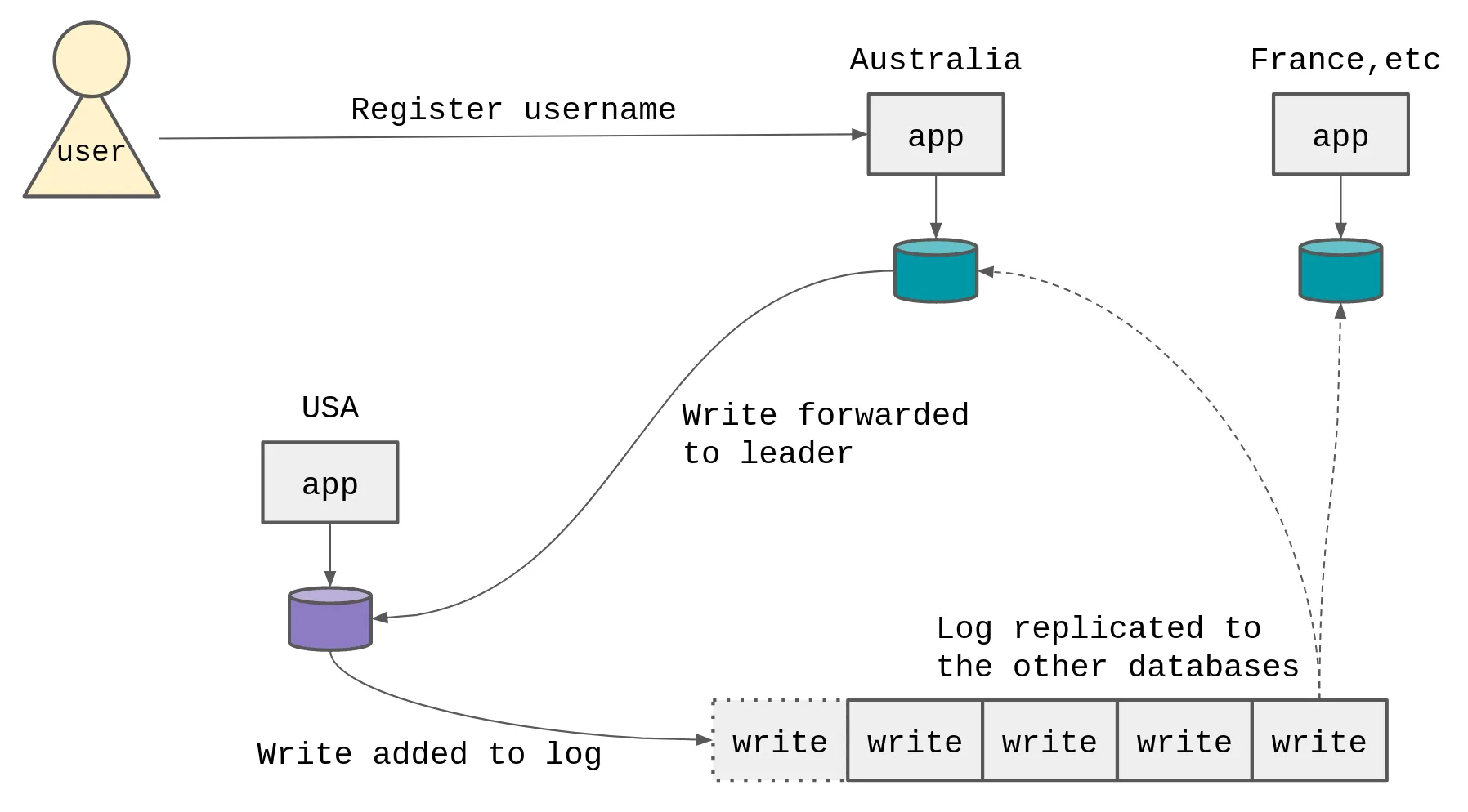

To read the writes, we need replication. The log needs to be replicated back to the Australia database.

Read your own writes

The Australia database should only return a successful response to the user once it has received a segment of the log that contains the write that was originally forwarded to the USA database. This ensures that the Australia database can read its own writes.

If we didn’t care about the read-your-own-writes property, we could return to the user immediately and assume the replication would happen sometime later.

When we touched on the ‘Two choices’ earlier, we covered writes but not reads. We saw how the database suffers from the inter-region latency when forwarding a write.

The thing about reads is; we might not care. We might be perfectly happy that the France, etc database is slightly behind the other USA database. We might not care that the most recent write has not been replicated to the France database yet.

Eventually consistent

If we don’t care that the most recent write on the database leader (USA) has not yet been replicated to the France database, then we call this system eventually consistent. That is, eventually the write will be replicated to the France database, but we don’t know exactly when. And we possibly don’t care (depending on the exact usage of the system).

If we did care, we’d call this system strongly consistent and we would require the leader to only consider the write successful once it had been fully replicated to all the other databases. In this case, all the databases would have all the data all the time, but writes would be much slower, as we would have to wait for all the databases to receive and reflect the write.

On reads

There is one final way to get strongly consistent properties of the databases, without requiring the inter-region latency hit on writes. (As we have just been discussing, the new data is replicated across the regions when it’s written).

This is number 2, from when we covered the ‘Two choices’. On reads.

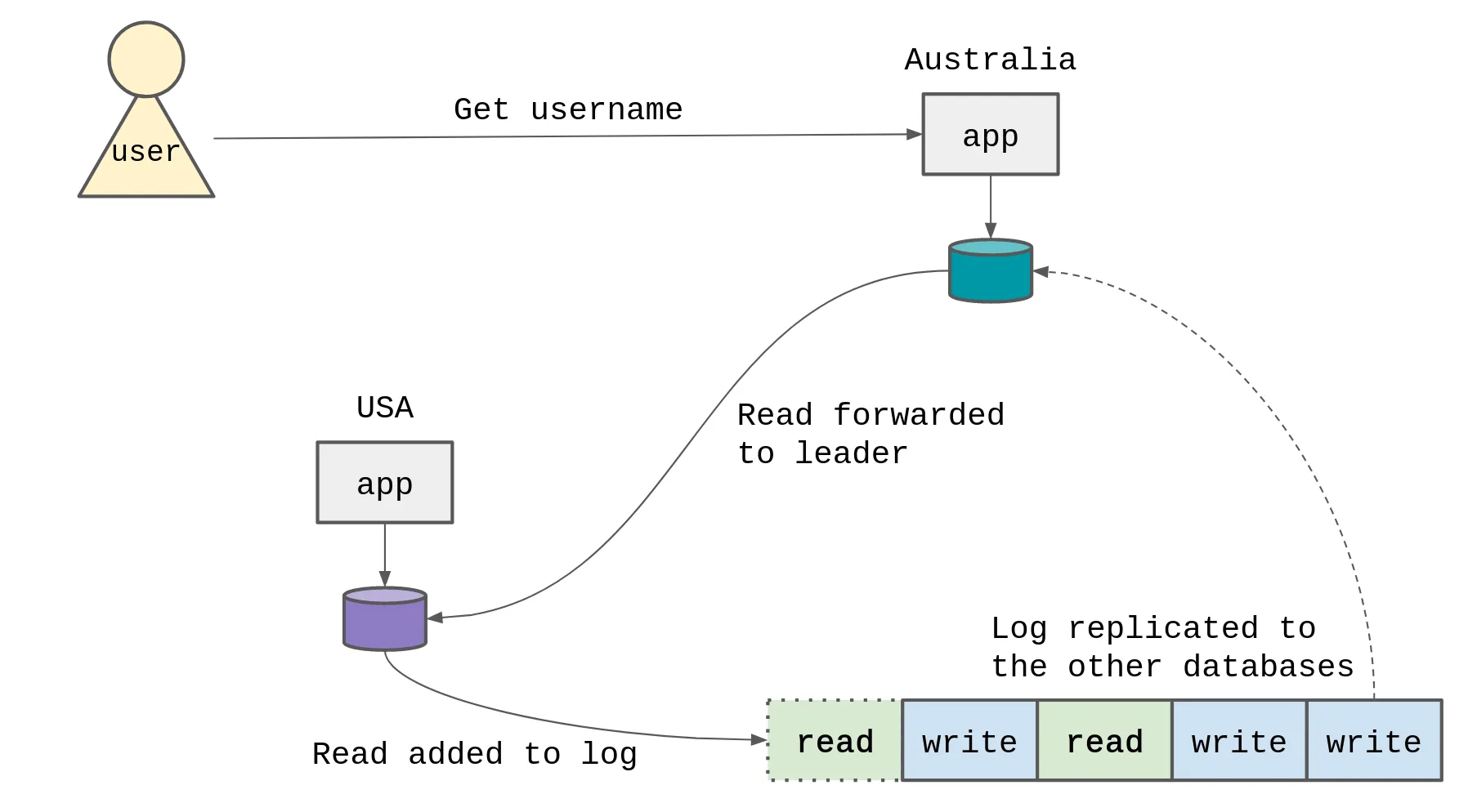

Read forwarding

Imagine that we hadn’t required the write to be replicated to the Australia database when it was added to the log, and instead embraced an eventually consistent system.

But we had a small number of cases where we needed to make sure that the read we were performing was strongly consistent (that is, it reads exactly the data that any database has, not just the data that this database has received yet from replication.)

To perform a one-off strongly consistent read, we could forward that read to the leader (USA), add that read to the database log, and wait for the read to be replicated back to the Australia database. Once the Australia database receives the read in the log, it knows that it has all the most up to date data for that specific point in time, and can safely execute the read from its local datastore.

But once again, we have to suffer the cross-region latency for the read to be forwarded to the leader database and the log to be replicated back again.

What do we do?

As I said at the start:

The main thing stopping developers from adopting edge computing is data consistency.

We can put the apps near the users, and a copy of the data near the apps, but in doing so we sacrifice data consistency or we suffer network latency costs.

We can’t beat physics, and data can only be transmitted so fast across the network between regions. This means that we have to make choices about what kind of data consistency we want, and importantly we have to decide: at which point do we want to deal with the latency.

Most internet apps are read-heavy, there are more reads than writes, so largely it makes sense to deal with the latency on writes. We can do this by forwarding the writes to some leader for that piece of data (e.g. the log for usernames), and waiting until that write is replicated back to us (so we can read our own writes).

Some examples

The following are some examples of database systems that are optimised for read-heavy applications where we eat the latency cost on writes.

- Turso: writes are forwarded to the leader, reads are local.

- Litefs: writes are forwarded to the leader, reads are local.

- Postgres warm standby in ‘synchronous’ mode: writes are committed to the leader and replica at the same time, reads can be from the replica.

–

Footnote: Beat the system

Finally it’s worth mentioning, some databases try and beat the system by structuring data in a specific way. For example, giving the Australia database ownership over all the Australian data and user requests, and not letting region-specific datasets overlap with each other. This can work, but it adds some other difficult constraints when you want to query across datasets or join them together.