The following is a retrospective on how publicly releasing source-code is not enough for a software to be considered open-source. The author argues that simple things such as good documentation are critical for someone to understand a codebase.

https://fuzzypixelz.com/blog/source-code-is-not-enough/

Premise

A program is free software if the program’s users have the four essential freedoms:

- The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0).

- The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1). Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

- The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help others (freedom 2).

- The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3). By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

— What is Free Software?, gnu.org

People will often claim that since X is Free and Open Source Software, every user of X is enabled to hack on it and bend it to their will.

I will argue that this is rarely the case (1); after so many hours of doom-scrolling the orange website, the contrarian in me is finally taking over.

Cost of building software

Aseprite is a popular sprite editing program. You can buy a copy of it on the official website for $20 and get access to binaries for Windows, macOS, and Ubuntu. The thing is, the source code for Aseprite is available on GitHub — released under EULA for Aseprite which disallows the re-distribution of the source code, among other things.

Still, you can just compile it from source! The developers were nice enough to provide detailed, albeit quite involved, compilation instructions. There are even pre-built binary releases of their fork of Skia, which Aseprite depends on; without which you would’ve had to go through the trouble of building Skia too.

If you enjoy watching processors churn out machine code you might be wondering: what’s the catch? After all, you can even tweak the source code a little before running ninja.

You may only compile and modify the source code of the SOFTWARE PRODUCT for your own personal purpose or to propose a contribution to the SOFTWARE PRODUCT.

— END-USER LICENSE AGREEMENT FOR ASEPRITE

Well, it turns out that building software isn’t completely painless. Here’s a list of potential issues you might encounter:

- Inability to satisfy build dependencies because your system is too old or too new.

- Abhorrent compile times on older and cheaper hardware.

- Hard to debug build failures because “works on my machine” only concerns the developer’s local environment.

Not only that, but you will deal with these issues every time there is a new Aseprite version, and every time you decide to move to another system.

Suddenly, having someone else take care of this mess sounds like a good idea. That’s probably why most Aseprite users go this route (2).

There is a cost associated with building Aseprite, whether you know what ninja is or not; freedom (1) doesn’t attenuate this burden. Granted, if you had freedoms (3) and (4) you could’ve made use of an economy of scale, serving many users automatic builds for a much smaller cost. But the cost is still non-zero nonetheless. And that’s an opportunity to sell a service. The Aseprite developers decided to reserve the right to sell said service, that is their business model and is well within their legal rights. I am not making a moral judgment here.

Where is the Heckin’ Manual?

When was the last time you took a tour inside Linux, Chromium, LLVM, or VS Code? It’s nice that these titans are Free and Open Source Software, but their codebases are unapproachable to a casual user. Even with knowledge of the domain, potential hackers will need to make their way through layers of cleverness, accidental complexity, and technical debt before making that small change.

VS Code is open-source software. Nobody cares. Everyone uses the plugin interface designed to extend the editor in well-defined ways. That’s why you never see drastic changes to its UI like you would in Emacs — and that might even be a good thing. Point is, the rest of the codebase isn’t designed to be hackable, and so very few people will actually attempt to hack on it.

I will be taking the venerable Arthur Whitney as my scapegoat here. When Arthur was only 11, he was introduced to the irredeemably terse APL programming language by Ken Iverson himself. This might have contributed to what people call “Arthur Style” — a tendency to fit as many symbols as possible onto the screen at once, so that you may reason about all of it simultaneously.

I came across several attempts at deciphering Arthur’s b programming language. In the words of the author (3) b is fast, interactive, and isomorphic to C.

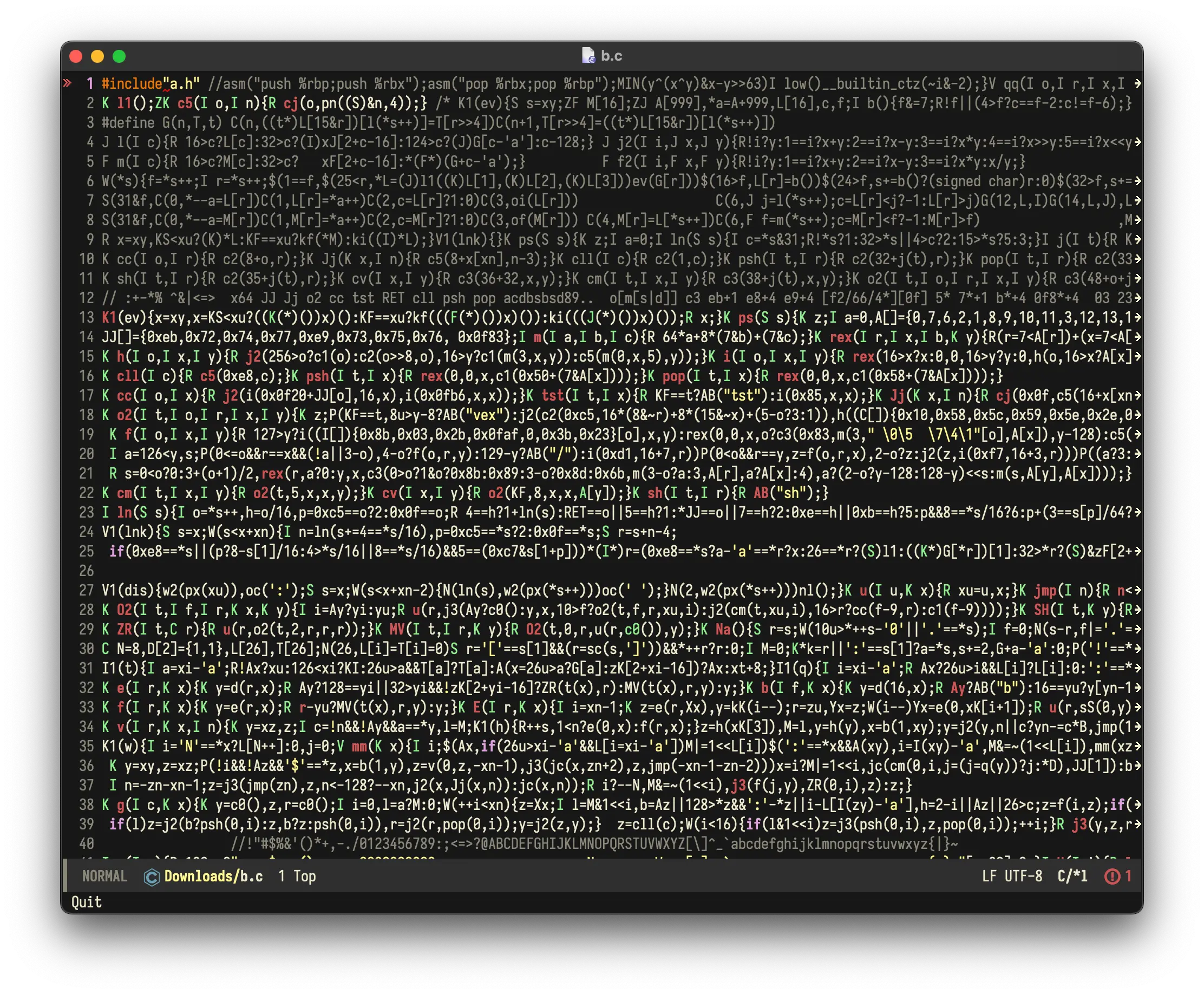

b.c: Almost all the C source code of the b interpreter; the file only spans 55 lines.

The above code contains exactly one comment which reads:

// :+-*% ^&|<=> x64 JJ Jj o2 cc tst RET cll psh pop acdbsbsd89.. \

o[m[s|d]] c3 eb+1 e8+4 e9+4 [f2/66/4*][0f] 5* 7*+1 b*+4 0f8*+4 \

03 23 2b 3b (6b 83) 89 8b ..

Need I say more?

b is an extreme example of an inaccessible FOSS project. However, this little anecdote raises valid concerns: what if the documentation of an open-source codebase is scarce or (in this case) non-existent? What if the algorithms and data structures are so complex that understanding them through source code is no better than observing them through machine code? Because then you might as well reverse-engineer the whole thing!

The Free Software Foundation considers obfuscated JavaScript blobs to be unfree, even though they are source code. As long as we’re being whiny hackers, why not go the extra mile and declare all unreadable code unfree? Where exactly would you draw the line here?

If the issue with a binary blob (that you’re legally allowed to modify, run and redistribute) is that it’s hard to decipher, then any sufficiently complex and unapproachable FOSS program is equally unfree.

Upstream has the high ground

The amount of resources needed to maintain a fork of a FOSS project is roughly proportional to the amount of effort put into the main project. A handful of developers cannot play catch-up with a fast-moving upstream.

A good example of this is what I like to call “The Tragedy of llvm-hs The Complete”. In a nutshell, LLVM is a C++ codebase by default, and only wraps some of its C++ API in the official C API. Consequently, the Haskell people had taken on the brave task of implementing some features which were missing in the C API. Needless to say, this is an enormous maintenance burden.

Since anyone last touched our FFI layer, the LLVM C API has been updated significantly. Most importantly, the LLVM C API now has functions which do things for which we have hand-rolled code in our FFI.

Where the LLVM C API now has a function that does something, and we have hand-rolled code that does something, we should remove our hand-rolled code and instead call the LLVM C API function.

This is quite a large undertaking, effectively being an audit of the entire FFI layer. However, it can be done piecewise, module-by-module.

— @andrew-wja’s PR358 on

llvm-hs, August 2021

This is very unfortunate. It’s the reason why Hackage still distributes bindings for LLVM 9 which was released back in 2019. Meanwhile, the llvm-hs project is busy trying to roll out support for LLVM 12.

At the time of writing, the latest LLVM release is 15.0.3. This is a case where downstream doesn’t have enough resources to maintain non-trivial modifications to a giant upstream project, let alone influence its development.

Truly Free Software

A true definition of free software would also include the freedom from tinkering with source code. A truly free program would be designed from the ground up with customizability and extensibility in mind, through an interface accessible to regular users, not just developers.

A truly free program would be independently audited for security and privacy. Knowing that their programs were verified not to perform arbitrary instructions would put users at ease. Such a practice could be enforced through regulation.

Requiring that the source code be public doesn’t guarantee that it will be checked for security and privacy let alone for good engineering practices. The fact that most free software is privacy-respecting is due to cultural circumstances and the personal views of its developers, and not a binding contract.

Join the TFS Foundation today.

Just kidding.

(1) I had the idea for this post back in September and went through three drafts before finally settling on what you’re reading right now. ↩

(2) Granted, most of these people are artists. So they likely aren’t even aware of what I just described; they most probably wouldn’t compile Aseprite from source even if they knew they could. ↩

(3) Technically, the code found at https://kparc.com/b/ includes no license, and the README doesn’t credit Arthur himself. Still, it’s safe to assume b is his project: it fits his unique style. ↩