The following articles explains the steps a researcher took to reverse engineer and find the flaws in a E2E encrypted messaging app.

https://crnkovic.dev/testing-converso/

I recently heard this ad on a podcast:

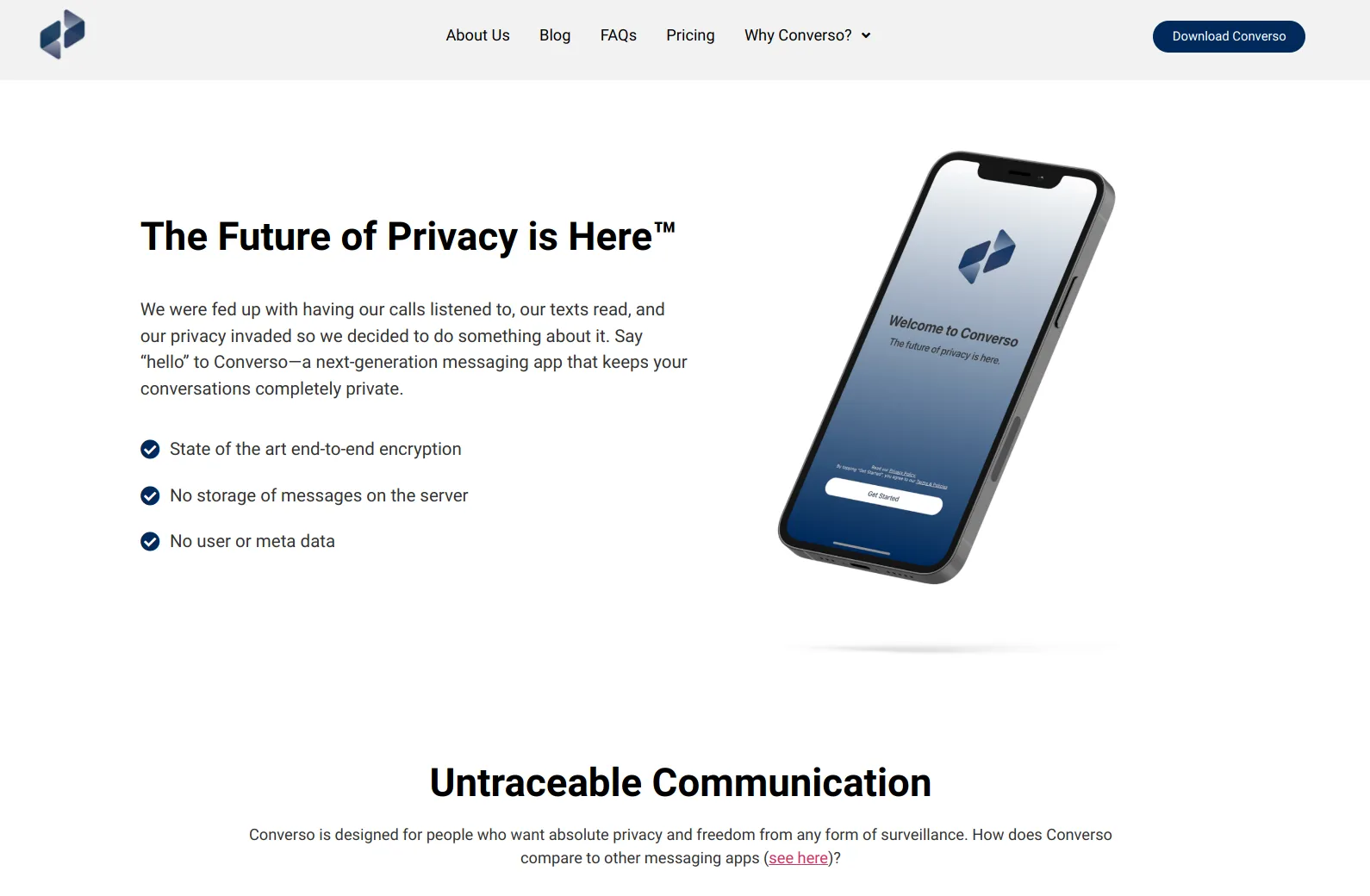

I use the Converso app for privacy because I care about privacy, and because other messaging apps that tell you they’re all about privacy look like the NSA next to Converso. With Converso, you’ve got end-to-end encryption, no storage of messages on the server, no user or metadata. […]

No metadata? That’s a bold and intriguing promise. Even Signal, the gold standard of encrypted messaging, with its Double Ratchet and X3DH components, still manages to leak a ton of metadata.

I had taken it for granted that end-to-end encrypted messaging apps couldn’t get around the fact that there needs to be someone in the middle to take an encrypted message from one person and deliver it to another – a process involving unavoidable metadata, such as who you are talking to and when. According to Converso, however, messages ‘bypass’ a server and leave no trace.

As far as I was aware, the only way you can take the middle-man out of the picture would be to transition from a client-server model to a peer-to-peer client-client model, but this idea comes with too many problems:

- Both the sender and receiver would need to be online at the same time. Offline messaging wouldn’t work – and the feature of sending messages asynchronously to a disconnected user is a requirement in a modern chat app.

- The parties would need a way to establish a direct connection with each other, but presumably both are behind NAT routers. And how do they find each other’s IP addresses to begin with? (Hole punching exists but that too relies on a third-party to broker two connections.)

Unfortunately, Converso is not open source and their website is totally silent on cryptographic primitives and protocols, which is highly unusual for a self-proclaimed ‘state-of-the-art’ privacy application. By comparison, Signal, WhatsApp, and Telegram, each [1, 2, 3] make public in-depth technical explanations of their end-to-end encryption systems, which are formally tested and reviewed by external experts. Converso on the other hand claims that they’re waiting for patents before they open source their code.

That leaves reverse engineering or decompilation as the last resort to view its inner-workings. So I took a look inside Converso’s Android app to test its claims, and to roughly compare its novel encryption protocol against established encrypted messaging apps like Signal.

Screenshot of conversoapp.com/about-us/

Screenshot of conversoapp.com

Grabbing their APK

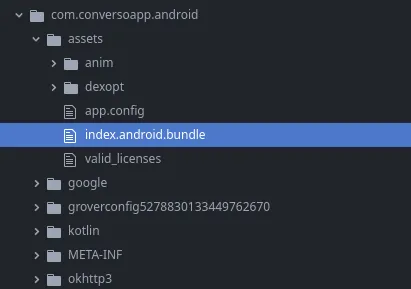

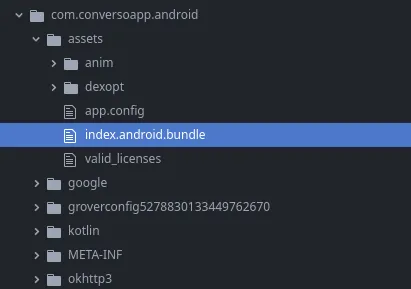

Before opening the app, I decided to dive into its contents. I downloaded the APK and had a peek inside.

Thankfully, the app is written in JavaScript (React Native). The file index.android.bundle contains all the code for the app and most of its dependencies – minimised to reduce its size, but still readable.

Converso’s package contents

First, some searches. Let’s see what domain names are referenced.

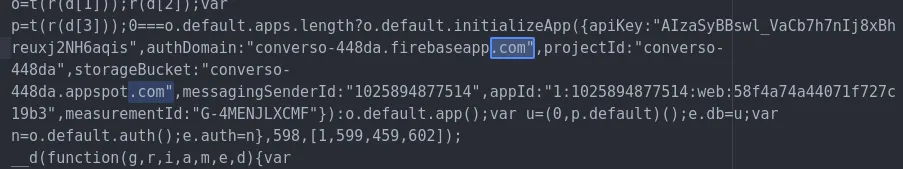

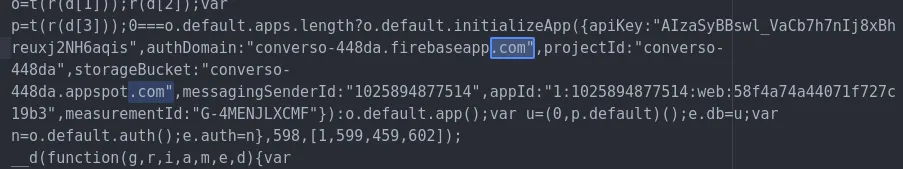

Here’s the app’s Firebase config

First thing I notice is that they’ve included measurementId in their Firebase config, which is an optional field a developer can include to enable Google Analytics tracking. Nothing wrong with that, but it surely shouldn’t exist in an app that claims ‘absolutely no use of user data’.

The next interesting domain name I see is zekeseo.com. This seems to be a different website by Converso’s creator, offering SEO marketing services. An odd inclusion.

‘zekeseo.com’ is included in two functions

This code says, in a nutshell, that if your chosen username doesn’t include an @ symbol, then the app will make it an email address by suffixing @zekeseo.com. I guess something else – a backend – wants usernames to be in the format of an email address, but the frontend doesn’t.

Next, there’s a reference to a URL on Pixabay. This appears to be the fallback URL for a user’s profile picture. I’m not sure why it needs to be an external URL – this seems like a mistake.

The default profile picture is downloaded from cdn.pixabay.com

The default profile picture hosted on Pixabay.com

Looking for crypto code

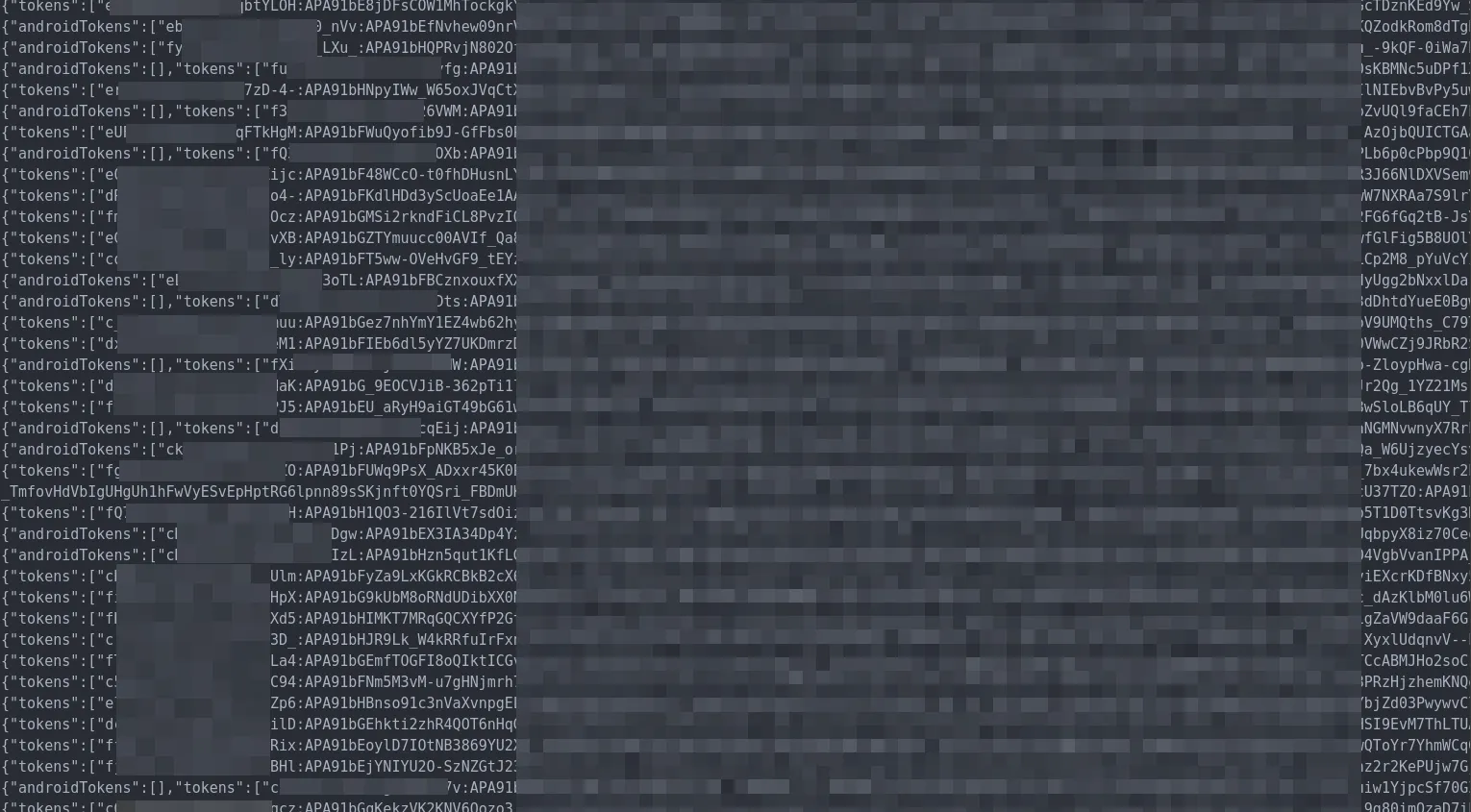

When I start searching for cryptographic primitives, I find references to AES and RSA. I was expecting elliptic-curve cryptography – because I’m not aware of any modern encryption protocol that doesn’t use ECC.

Anyway, it looks like messages are being encrypted – evident from functions named encryptMessage and decryptMessage. That’s a start, however it doesn’t mean the encryption is meaningful. How are those messages encrypted, how are encryption keys generated and shared, how often are keys replaced, how are keys and messages authenticated, and how do encrypted messages make their way from the sender to the recipient?

Looking at the code surrounding some of those encryption functions, I see references to Seald and an API hosted on a seald.io subdomain.

The app uses a ‘Seald’ SDK

A quick look at Seald’s homepage answers many questions. Seald is a drop-in SDK for app developers to integrate end-to-end encryption ‘into any app in minutes’.

It’s obvious now: Converso hasn’t created any new groundbreaking encryption protocol, they’ve merely implemented this SDK. The app defers to Seald to handle the encryption components of the app.

Seald’s homepage

That still leaves questions outstanding about how Converso, and by proxy Seald, is able to transmit messages without storing messages on a server, and without obtaining metadata? Does Seald’s SDK really allow Converso to do all it claims?

Fortunately, the answers to all these questions can be found in Seald’s developer documentation. No need to look any further at Converso’s source code.

How Converso encryption really works – its claims vs reality

Whenever you send a message to another user in Converso, here’s what happens:

- The sender fetches the RSA public key

Pkassociated with the recipient’s phone number from a Seald server, and trusts it as authoritative. - The sender encrypts their message

Mwith AES-256-CBC using an ephemeral symmetric encryption keyK. - The sender encrypts

Kwith RSAES-OAEP so that only the owner ofPkcan decrypt it. - The sender constructs a MAC to authenticate the message,

Mac, with HMAC-SHA-256. - The sender sends cleartext

Mac, and the encrypted copies ofMandK, to a server via a network request. The server later delivers these to the recipient.

That’s pretty much it.

There’s no peer-to-peer networking – the app uses a classic client-server architecture.

Now that we understand Converso’s encryption protocol, we can go through some of the claims made on their website and see how they match reality.

Update (2023-05-13): Since publishing this post, Converso has removed many of these statements. The verbatim quotes below previously existed on Converso’s website or official marketing materials.

Claim: ‘State of the art end-to-end encryption’

Verdict: False.

Screenshot of conversoapp.com/about-us/

For an encryption standard to be considered ‘state-of-the-art’, it would need to at least include all the features of modern encryption protocols. Converso uses plain old RSA, one of the oldest encryption standards available.

To begin with, random number generation looks fine. As a source of random for generating secure keys, Converso appears to utilise java.security.SecureRandom on Android devices, and Apple’s CSPRNG on iOS.

Next, how does Converso protect against man-in-the-middle attacks? That would be the ability to confirm that who you are talking to is really the person you think you’re talking to – and not an impersonator or a middle-man. Converso relies on a third-party authority – Seald’s servers – as the sole certificate authority for mapping identities to public keys. This third-party holds a god-like power to impersonate anyone. There’s nothing akin to Safety numbers in the Converso app to ensure the integrity of an encrypted conversation – there’s no feature in the app to view your contact’s public key, and no notification if a key were to change. That’s a hard fail.

Note (2023-05-17): I want to make clear that I’m not calling the security of Seald into question. Seald doesn’t echo the promises that Converso makes about its end-to-end encryption protocol. Seald’s protocols, which are well documented, seem perfectly fit for many use cases – but not an end-to-end encrypted messaging app that compares itself to Signal. Also, some of these failures, such as a lack of safeguarding against man-in-the-middle attacks, are a result of Converso’s poor implemention of the SDK.

Next up, message integrity and authentication. How are messages guaranteed to have not been tampered with in transit, and how can we ensure they really came from the sender? Since all public keys are already untrustworthy, meaningful message authentication can’t exist.

Forward secrecy? This doesn’t exist. Unlike with the established encrypted messengers Converso compares itself to — Signal, WhatsApp, Telegram, and Viber – if a Converso user’s device is compromised, the keys on that device could be used by a sophisticated adversary to decrypt past conversations, even if they had been deleted from the user’s device. Asymmetric key-pairs in Seald have a default minimum lifespan of three years (by contrast, key-pairs in the Signal Protocol are replaced after every message).

Future secrecy (or post-compromise secrecy)? Modern encrypted messengers have self-healing properties which prevent an attacker from decrypting future messages after an earlier device compromise. Converso makes no attempt at this.

Results:

| Property | Converso | Signal, etc. |

|---|---|---|

| Some kind of encryption | Yes | Yes |

| Protection from man-in-the-middle attacks | ❌ | Yes |

| Message authentication | ❌ | Yes |

| Forward secrecy | ❌ | Yes |

| Future secrecy / Post-compromise secrecy | ❌ | Yes |

Claim: ‘No servers’, ‘No storage of messages on the server’

Verdict: False.

Converso claims it doesn’t use servers

Messages and keys are transmitted to and delivered by a server. Of course there are servers.

Claim: ‘Absolutely no use of user data’, ‘No tracking’, ‘When you use Converso, none of your data is stored on our servers, or anywhere else’

Verdict: False.

Screenshot of conversoapp.com/faqs/

Not only does Converso include a Google Analytics tracker to record how you use the app, it also collects phone numbers for every account, plus unavoidable metadata surrounding every message or key sent or received. All of this data is stored on servers.

Additionally, presumably due to a developer error, every Converso user sends a HTTP request to cdn.pixabay.com to download this default profile picture. According to Pixabay’s privacy policy, they record those requests – along with IP addresses and device details.

Converso’s claim that messages leave behind ‘absolutely no metadata’, is very wrong, including these more specific declarations:

Where you’re visiting from [is secret]

When you use the app, your IP address, along with your location and device details, is handed to Seald, Google Analytics, and Pixabay.

Who you are [is secret]

Registration requires a phone number, which is stored by a server.

Who you’re talking to [is secret]

Messages are addressed to phone numbers and delivered via servers. The server needs to know the recipient of every message so it can route it to the correct device. It knows who you are talking to and when.

Claim: ‘It’s not possible to circumvent the platform’s end-to-end encryption’, ‘Every message sent is end-to-end encrypted, meaning that it can only be read by its intended recipient’

Verdict: False.

As demonstrated above, Converso’s encryption protocol is rudimentary and susceptible to a multitude of attacks.

Since key-pairs are entirely untrustworthy, there’s no guarantee of security when using Converso. Converso’s encryption protocol relies on a trusted third-party intermediary always behaving honestly.

Claim: ‘The same individual that started WhatsApp coincidentally founded Signal too’

Verdict: False.

Screenshot of converso.com

A WhatsApp co-founder did also co-found and contribute to the foundation that now develops Signal, but that happened eight years after Signal’s launch. The foundation ≠ Signal.

Signal was released in 2014 by Moxie Marlinspike’s Open Whisper Systems, however it has a history before that as TextSecure and RedPhone since 2010. In 2018, Brian Acton, co-founder of WhatsApp, helped to launch the non-profit Signal Technology Foundation, whose mission is ’to support, accelerate, and broaden Signal’s mission of making private communication accessible and ubiquitous.’

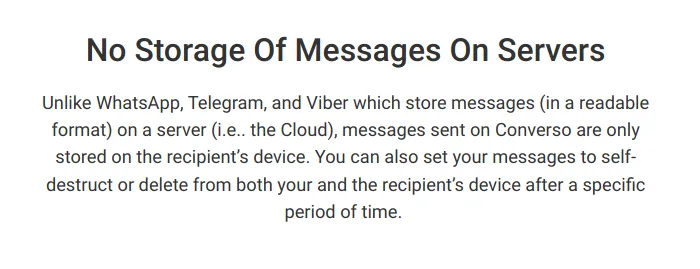

Claim: ‘WhatsApp, Telegram, and Viber […] store messages (in a readable format) on a server’

Verdict: False or highly misleading.

Screenshot of conversoapp.com/converso-security/

WhatsApp and Viber have both implemented the Signal Protocol. Encrypted Telegram conversations use MTProto. These are both widely known and well-documented encryption protocols which have been formally analysed by external researchers.

Encrypted messages are not stored in a readable format on the servers of WhatsApp, Telegram, or Viber. (In Telegram, end-to-end encryption is an opt-in feature – regular unencrypted messages are exposed to a server.)

Converso elsewhere asserts that WhatsApp ‘generates unencrypted chat backups in Google Cloud or iCloud’, however this is not quite true. WhatsApp backups are optional and can be safeguraded with end-to-end encryption (although they haven’t yet made this the default).

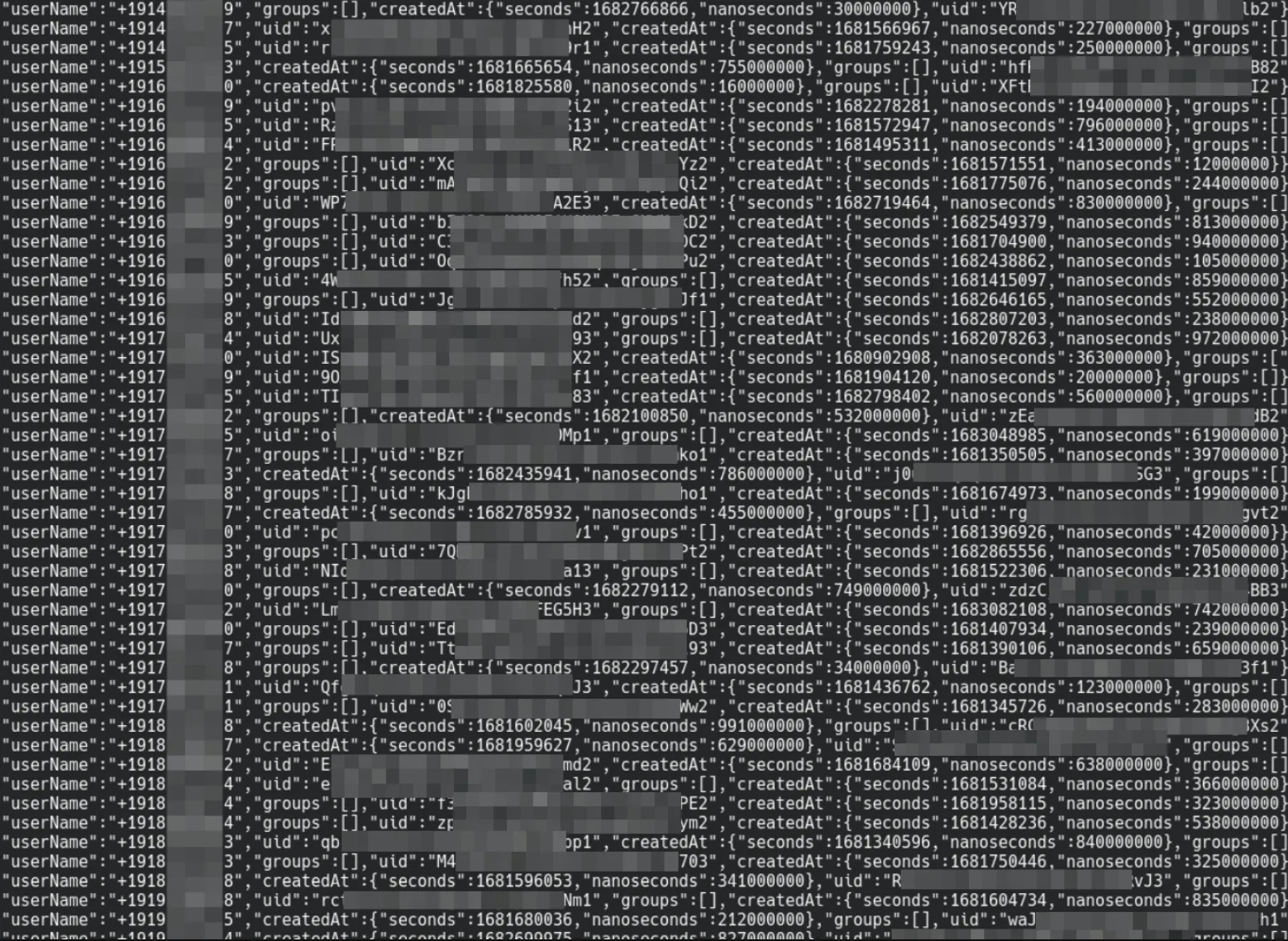

Claim: ‘Every conversation that takes place on our platform is part of a decentralized architecture’

Verdict: False.

Converso uses central servers to transact keys and messages. Converso doesn’t involve decentralised architecture – it uses a traditional centralised client-server model.

Claim: ‘[Signal] relies on Amazon S3 to distribute blockchain data’

Verdict: False or highly misleading.

Signal comes with support for peer-to-peer payments in ‘MobileCoin’, a private cryptocurrency, however this is an optional and unpopular feature. Regular end-to-end encrypted messages in Signal don’t use MobileCoin or any sort of blockchain data.

tl;dr

The take-home message is that, once again, not all information on the internet is factual. Converso misrepresents itself as a state-of-the-art end-to-end encrypted messaging app, which couldn’t be further from the truth. The reality is that the wild claims Converso makes on its website – the promises it makes about its app’s security, plus the shade it throws on premier encryption tools – are all provably false. It’s therefore my opinion that you shouldn’t rely on Converso for any sense of security, and you certainly shouldn’t pay $4.95/month for it.

Screenshot of conversoapp.com/download-converso/

But wait – it gets much, much worse

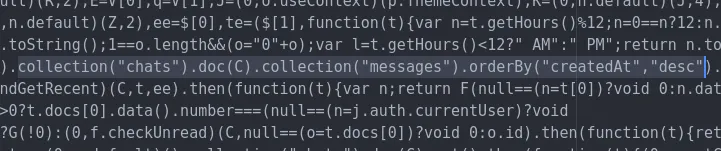

As I was finishing up the above post, I noticed something a little strange in the code – something I’d glossed over earlier. There are a ton of references to what looks to be functions related to Google’s Firestore database.

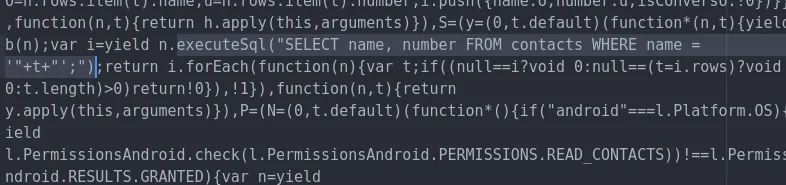

Earlier in the code, I saw SQLite used for some lighter operations, such as indexing local device address books. I assumed SQLite was also used for other things, like messages, and that servers were only utilised for data transport, not longer-term storage – I was wrong.

Some SQLite code found earlier (spot the bonus vulnerability)

It looks like Firestore is the database framework used by Converso for storage of all kinds of app data, including messages sent and received, call logs, user registration data, and possibly other classes of user content.

Firestore databases for ‘chats’ and ‘messages’

This is shocking and confusing to me, since Firestore is a cloud-based database hosted by Google. It’s not an offline-only internal database interface that you would expect an app like this to use. And Firestore seems to be used for a lot a data that should certainly be managed offline. I see Firestore database collections and subcollections named users, chats, messages, missedCalls, videoInfo, recents, rooms, fcmTokens, phoneRooms, phoneInfo, usersPublic, loginError, callerCandidates, and calleeCandidates.

Surely this Firestore database is locked down… right?

With any online database, you would expect server-side access control rules to be in place to prevent unauthorised access of sensitive data.

I decided to try those Firebase credentials I found earlier in the app’s code to check whether the data was being properly secured by Firestore’s Security Rules. Those credentials alone should not allow unrestrained access to sensitive data in this database.

I wrote a few lines of code to see what would happen if I tried to pull from the users collection:

initializeApp({

apiKey: "AIzaSyBBswl_VaCb7h7nIj8xBhreuxj2NH6aqis",

authDomain: "converso-448da.firebaseapp.com",

projectId: "converso-448da",

storageBucket: "converso-448da.appspot.com",

messagingSenderId: "1025894877514",

appId: "1:1025894877514:web:58f4a74a44071f727c19b3"

});

const db = getFirestore();

const querySnapshot = await getDocs(collection(db, "users"));

Here’s what I got:

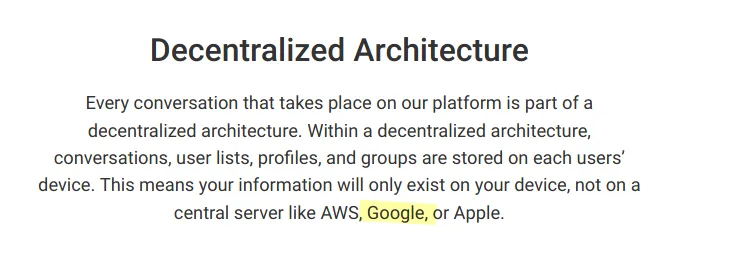

A small portion of the users collection

Looks like I accidentally breached Converso’s user database. The users collection, which is open to the internet and publicly accessible, contains the registration details for every Converso user. Phone numbers, registration timestamps, and the identifiers of groups they’re in (i.e. who is talking to who).

Many of the other database collections are equally totally public. The collections fcmTokens, loginError, missedCalls, phoneInfo, phoneRooms, rooms, usersPublic and videoPublic don’t require any sort of server-side user authentication to access.

(If you’re not familiar with Firestore, this mistake is virtually the same as deploying an internet-facing SQL database with no username or password required to access – anyone can read or write anything!)

Converso’s metadata is public

Not only does Converso collect and retain massive troves of metadata it claims doesn’t exist in the first place, this metadata is publicly accessible. If you make a call, that information is broadcast to the world and can be viewed in real-time by anyone interested.

This data is being stored unencrypted by Google servers – highly ironic for a business that rails against ‘Big Tech’ in its marketing messages (and Google specifically).

Converso is designed for people who want absolute privacy and freedom from any (government or Big Tech) form of surveillance.

— conversoapp.com

Screenshot of conversoapp.com/converso-security/

Exploring the remaining Firestore collections

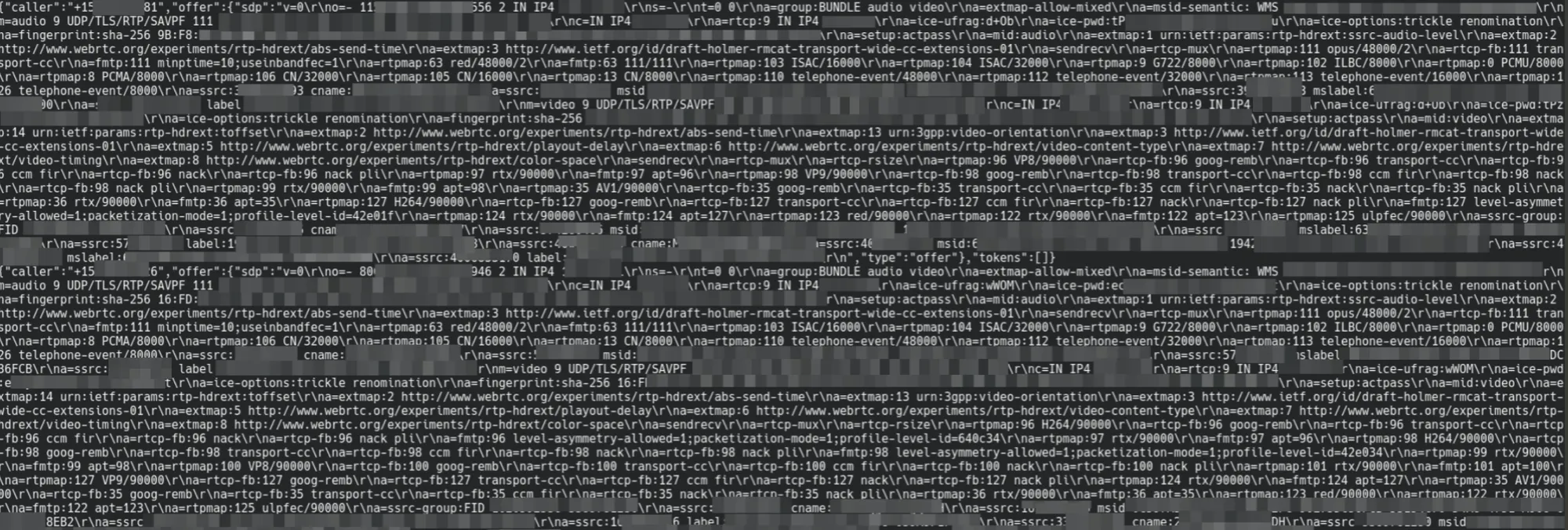

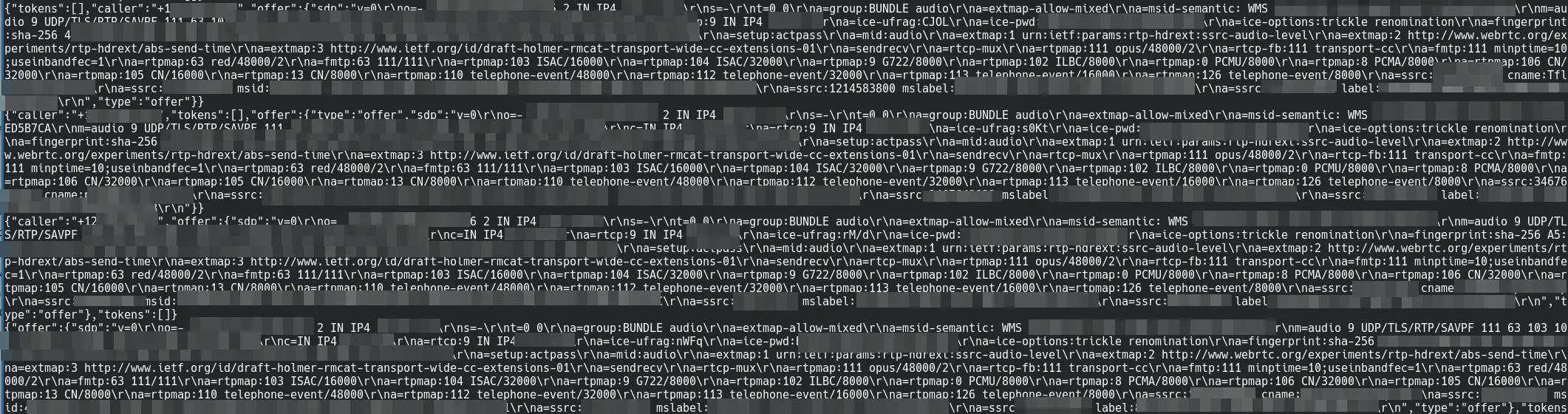

The rooms collection contains metadata surrounding video call sessions. (Video and audio streams between users use WebRTC.)

A small portion of the rooms collection

Similarly, phoneRooms contains metadata for audio calls made in the app.

A small portion of the phoneRooms collection

The fcmTokens collection appears to contains a long list of FCM registration tokens for every user. These are identifiers issued by GCM connection servers to allow clients to receive notifications and other types of in-app messages.

I’m not sure how exactly these tokens are used by Converso, however Firebase’s documentation makes clear: ‘registration tokens must be kept secret.’

A small portion of the `fcmTokens` collection

I couldn’t access the chats or messages collections – it looks like there is some kind of permissions scheme in place here, finally. I’m not sure what these security rules are – I might come back to this later. Back to the code:

Converso’s online message database

There are two categories of messages in Converso: cleartext messages and encrypted messages. Both are stored in the messages Firestore collection hosted by Google. Their entries look like:

{

createdAt: <timestamp>,

number: "<sender phone number>",

message: "<cleartext message>",

encryptedMessage: "<encrypted message>",

messageContent: "<i don't know what this is yet>",

tokens: ["<i don't know what this is yet>"],

selfDestruct: <time-to-live>, // optional

}

An example Converso message entry

These categories of Converso messages are not encrypted at all:

- Image messages. These are message entries with

isImage: trueand a cleartextimageNamefield containing the cleartext filename of the image. Image files are transferred in an unencrypted format using Firebase’s Cloud Storage service. - Animated images. These are message entries with added

urlandisGif: truefields. When the recipient device receives a message of this kind, they will automatically download the referenced image without prompt – and there’s no way to disable this. This seemingly opens an obvious and serious vulnerability: anyone can get the IP address of any Converso user by simply sending a message pointing to a URL hosted by the sender. - Requests to ‘clear’ the messages in a conversation. These are cleartext message entries with a

isClear: true. - Requests to ‘delete’ a previous message. These are cleartext message entries with

isDelete: trueand amessageIdfield referencing a message to remove. - Notifications that a screenshot is taken. If the app detects you taking a screenshot, it will send a cleartext message with the cleartext message

"Screenshot taken"andisScreenshot: true.

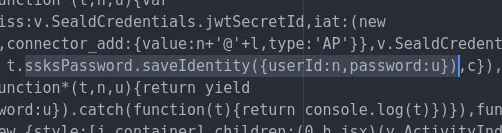

Encrypted messages, which contain the encryptedMessage string in their Firestore entries, are handed to the Seald SDK for decryption via its decryptMessage function. This function appears to transform a base64-encoded ciphertext into a plaintext string using the encryption method described above.

Invoking Seald’s decryptMessage

A closer look at ’encrypted’ messages

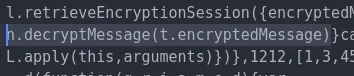

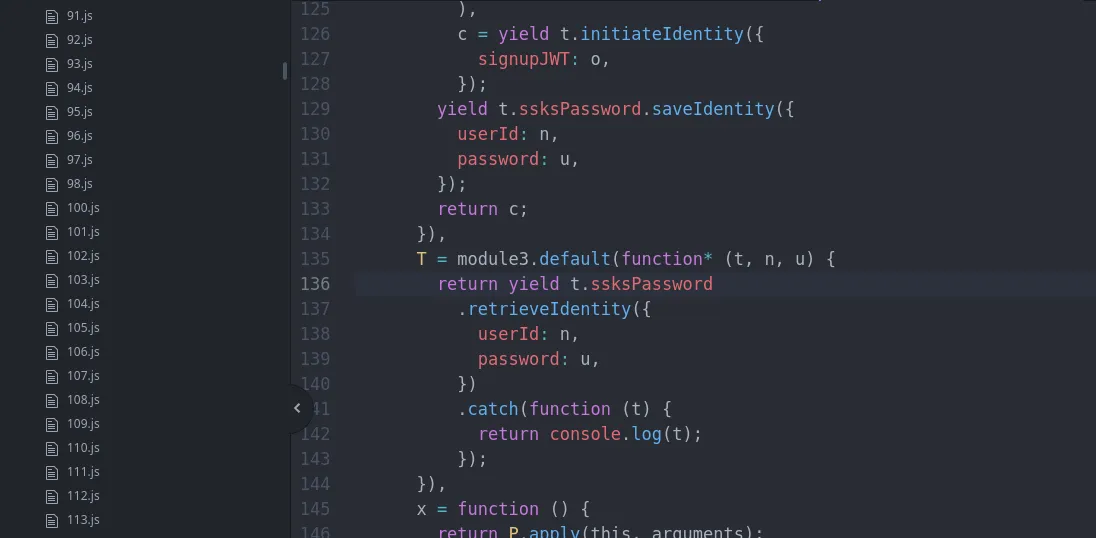

Further inspecting the Seald-related code, I notice Converso is using Seald’s [@seald-io/sdk-plugin-ssks-password](https://docs.seald.io/en/sdk/ssks-password/) module. According to the developer documentation, this allows Converso to use Seald’s ‘secure key storage service’ to ‘store Seald identities easily and securely, encrypted by a user password.’

So private keys are being backed up to Seald’s servers, encrypted with user passwords. If a user deletes the Converso app, they can later recover their super-secret RSA key by fetching an encrypted version from a server and decrypting it locally with their password. Once the key is recovered, they can decrypt old messages stored in the Firestore database.

But there’s a big problem with that: there’s no such thing as a password in Converso. To create an account, all you need to do is enter your phone number and verify an SMS code. If there’s no such thing as a password, what are these keys being encrypted with?

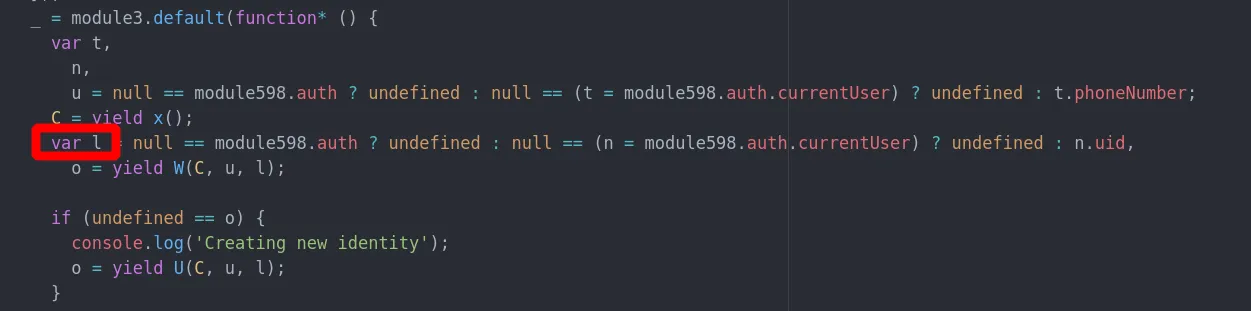

This code encrypts users’ secret keys with a password and uploads them to Seald’s backup service

It’s a little hard to trace where the password variable (u) comes from in this minimised JavaScript code. Time to bring in a debundler tool to make the code slightly more legible.

$ npx react-native-decompiler -i ./index.android.bundle -o ./output

Now it’s easier to trace variables across functions. With a better look, I can see that the code I’m looking at is inside a React Native component called ‘Seald’.

The code is now a little easier to follow

This variable contains the encryption password

It turns out the Seald username is the user’s phone number, and the encryption password is just their user ID. That’s really bad. Encryption passwords are just Firebase user IDs, and user IDs are public.

I already have a list of every user’s phone number and user ID – downloaded earlier from the public users collection. Which means I currently have the credentials to download and decrypt every Converso private key – granting me the ability to decrypt any encrypted message.

A short script to confirm this finding using the official Seald SDK:

Using the Seald credentials from the app’s code, plus a random user’s phone number and user ID from Converso’s public database

$ node test.js

[19:29:17.328 04/05/2023 UTC+10] info :seald-sdk - Seald SDK - Start

[19:29:17.338 04/05/2023 UTC+10] info :goatee - Instantiating Goatee

[19:29:17.341 04/05/2023 UTC+10] info :goatee - Initializing goatee

[19:29:18.993 04/05/2023 UTC+10] info :seald-sdk - Already initialized

[19:29:19.028 04/05/2023 UTC+10] info :goatee - Setting new default user...

[19:29:23.590 04/05/2023 UTC+10] info :goatee/database/models/User - Sigchain updated for user 2yXXXXXXXXXXXLEw. Sigchain matches with db: true

good password!

Oh no

I’m not going any further with my tests – I’m now only one step away from seriously invading someone’s privacy by reading a message expected to be encrypted and confidential.

Private keys are public, too

Not only is metadata public, but so too are the keys used to encrypt messages. Anyone can download a Converso user’s private key, which could be used to decrypt their secret conversations.

There’s no longer any real distinction between cleartext and encrypted messages – nothing is meaningfully encrypted. For your security, you shouldn’t use Converso to send any message that you wouldn’t also publish as a tweet.

These outrageous vulnerabilities were disclosed to Converso before this post was published.

- 2023-05-05: Vulnerabilities disclosed to Converso. Blog post drafted.

- 2023-05-05: Converso replied: ‘Thank you for your response and the time you have put into this matter. I have forwarded this to my CEO & CTO and we will address this immediately. We will get back to you as soon as possible with our detailed response.’

- 2023-05-05: Converso asks: ‘How were you able to decompile the source code of the app and what do you think should be done to protect against that in the future?’

- 2023-05-05: My response: ‘Your app is developed in React Native. Simply rename the Converso APK file to a ‘.7z’ file, and extract the ‘assets/index.android.bundle’ file. This file contains the bundled source code for Converso and its JavaScript dependencies. This is not something to protect against – other apps are the same. And besides, even if you could make this process harder, it is always unsafe to rely on client-side enforcement of server-side security.’

- 2023-05-05: Converso asks: ‘May we know what you do and where you are located? Thank you.’

- 2023-05-06: Converso says: ‘We wanted to let you know we have deployed a new version and are waiting for that build to be approved. We will continue to work on updates based on your feedback which was very much appreciated.’

- 2023-05-06: Apple approves the new version of their iOS app. In the release notes, Converso describes the new version as containing ‘minor bug improvements’ and ’even more next-generation security improvements’.

- 2023-05-06: Google approves the new version of the Android app.

- 2023-05-09: Converso says: ‘The vulnerability with Firebase rules have been patched and you are welcome to test it out. The other vulnerability of preset decryption keys has been implemented on our side, we are only waiting to get new credentials so that existing users will be reauthenticated. However, all existing messages sent with the old decryption keys are protected by firebase rules so they still cannot be read by outside parties.’

- 2023-05-10: Converso thanks me again for bringing the vulnerabilities to their attention. Blog post published.

- 2023-05-11 to 2023-05-12: The founder of Converso, Tanner Haas, tells me that he and his ’legal team’ have a problem with my article, and recommends I remove it. He sends me a series of emails accusing me of defamation and alleging that I am ’either an employee [of Signal] or Moxie himself.’ Meanwhile, Converso begins removing content from its website and marketing materials, including most of the false or misleading statements quoted in this article.

- 2023-05-14: Converso publishes a new blog post to its website in what appears to be a strategy to outrank, in search engine results, this web page and possibly others that point out Converso’s security flaws and misrepresentations. The new post includes the phrase ’testing Converso’s claims’ in its meta description tag.

- 2023-05-16: The Converso apps appear to be no longer available for download from the Google Play Store or iOS App Store. It’s not yet clear why this is the case, and whether the app will return. Either Converso has intentionally pulled the app, or the stores have an issue with it.

- 2023-05-16: In an email to me, Converso confirms that they voluntarily delisted the app from the app stores while they work to ‘address and improve the issues.’