The following is not the typical read you see on this blog everyday, but it’s rather a specification on the various different keyboard layouts each country adopts. This guide not only helped me grant that the really oldish keyboard (labeled in 2002) I was going to buy was really in my country layout, but also enabled me understand other interesting details about foreign layouts.

https://www.farah.cl/Keyboardery/A-Visual-Comparison-of-Different-National-Layouts/

This page compares the US English national layout with different national layouts used in other countries. For the obvious reason, these comparisons are limited to keyboard layouts based on the Latin alphabet.

Each comparison focuses on the differing arrangements of the alphabetical, numerical and typographical symbols in each national layout; due to this, all of them are presented within the same regular alphanumeric or “alpha” block, ignoring the remaining parts of a keyboard (namely: function row, navigation cluster and numeric keypad).

In each section, the base US English over ANSI layout and a different national layout are presented side by side, with the differing keys highlighted.

Index.

This document is comprised of the following sections:

- English layouts.

- Germanic and Nordic layouts.

- Baltic layouts.

- Mediterranean Romance layouts.

- Mediterranean non-Romance layouts.

- French layouts.

- Central and Southeastern European layouts.

- Turkic layouts.

English layouts.

English (USA).

Notes:

Considered the base layout for historical reasons.

Official in the United States of America; used in several other English-speaking countries with differing degrees of officiality.

This is the only major layout that does not use the tertiary (AltGr) or quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers. In fact, the RALT key is simply the right-side Alt key and not AltGr.

The standard for this layout was codified back when keyboards sold and used within the United States of America could be either of what we now call ANSI and ANSISO variants; nowadays, the former is ubiquitous within said country, although the latter still enjoys a significant presence in “Point of Sale” keyboards. On the other hand, both variants (plus BAE, but we don’t talk about that in polite company) are commonly seen in countries where this layout (or some extended version of it, as occurs in India) is used, even with a preference towards the latter over the former in some areas.

- In an ANSI keyboard, the Enter key is horizontal, 2.25U wide, and is placed on row 3; the \| (“backslash‑pipe”) key is placed immediately above, in row 2, with a width of 1.5U.

- In an ANSISO keyboard, the Enter key is vertical, 2.0U tall and is placed on rows 2 and 3, with a bottom half width of 1.25U and a top half width of 1.5U; the \| (“backslash‑pipe”) key is placed immediately to its left, in row 3, with a width of 1.0U (just like every other alphanumeric key).

- In both cases, those two keys occupy the same combined area.

- In both cases, the left-side Shift key in row 4 is 2.25U wide (in ISO and ISANSI keyboards, instead, the same area contains a 1.25U Shift key and a 1.0U alphanumeric key).

Given that both arrangements are equally valid (even if the latter may look “unusual” to some present-day American users), a custom keycap set that supports the English (USA) layout should provide both versions of the Enter and \| keys, independently of whichever other national layouts might be additionally supported (plus full ISO support, as described below, which simply means adding two more keycaps).

With the above said, given that the standard does not define the presence of a key between LSHIFT and Z, when this key is present (as is the case of ISO and ISANSI keyboards), there is no character assignment mandated for it. There are, however, two main traditions about what to do in this regard, one coming from personal computer keyboards and the other from terminal keyboards, as pictured above.

It’s important to remember that the terms ANSI and ISO, as used to refer to physical layout variants of a keyboard, depending on the shape and size of the left Shift and the Enter keys, and to refer to those two keys themselves (“ANSI Enter”, “ISO Enter”, etcetera), are modern monikers, and both are actually serious misnomers, as neither standards organization actually codified any of this — IBM did it. The terms ANSISO and ISANSI, to refer to (what we know call) “hybrid keyboards”, are even younger, and were derived directly from the former two words.

Yes, “BAE” is also a recent term, but, again, we don’t talk about it in polite company.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the English (USA) national layout (in its ANSI, ANSISO and ISO implementations) with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

- Islands: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

English (US international).

Notes:

IBM, not Microsoft, created this layout. The initial version had only a few extra key assignments, with several additions made later on; Microsoft forked an early version and made further incompatible changes. IBM’s version of this layout died with OS/2, while Microsoft’s branch survives to this day.

An extended layout adds new capabilities without modifying any of the original layout’s assignments (see the Finnish Multilingual and the Spanish Extended layouts for two examples of this); this layout, instead, is declared to be an extended version of the regular English (USA) layout, but it breaks the aforementioned rule by turning the key assignments of five typographical symbols into diacritic dead keys.

Despite its name, this layout’s real coverage is limited to a few Germanic and Western European languages, with inexplicable omissions even among this limited set; the OE ligature (Œ/œ), the middle dot (·) and the single low quotation mark (‚) are the most obvious ones. It does not help matters that some typographical symbols that are commonly used while writing in English in the United States (like “, ”, ±, — and –) are missing as well.

The arrangement of the extra characters that this layout does add is rather problematic, too; while some of them are fine [for example: the vowels with acute accents, the letter eñe (Ñ/ñ) and the angle quotation marks (« »)], others have been assigned in an inconsistent manner [like the three vowels with diaeresis/umlauts], even others have been placed where they clearly don’t belong [see where the letter C with cedilla (Ç/ç) is], and still others are placed in hard-to-reach assignments that are not in line with the high degree of usage they would be expected to have [like the pound (£), section (§) and degree (°) signs], despite readily available space remaining in the tertiary (AltGr) layer.

The addition of the five dead keys mentioned above is undeniably poorly done and further complicates actual usage: the grave (◌̀), tilde (◌̃) and circumflex (◌̂) accents take the places of the commonly used symbols backquote (`), tilde (~) and caret (^), respectively, while the acute accent (◌́) and the diaeresis/umlaut (◌̈) take the place of the extremely highly used symbols (adirectional) apostrophe (’) and (adirectional) quotation mark (") (which, to boot, don’t have an actual relation to said diacritics), forcing the usage of two-keystroke combos to get the proper symbols: (`+space for `, Shift‑’+space for “, etcetera). This is so uncomfortable, private individuals have created variations of this layout that either remove those diacritics or move them elsewhere.

As if the above wasn’t enough, Microsoft’s implementation overloads the apostrophe dead key with the cedilla diacritic (◌̧ ) to for no good reason (it’s only used for the letter C with cedilla (Ç/ç), which already has a direct assignment). Implementations in Linux produce a C with acute accent (Ć/ć) instead, which at least makes sense.

And just for the sake of further beating the (un-)dead horse, it will be noted that this layout provides no support whatsoever for the needs of the Hawaiian language: the macron diacritic (required to denote long vowels) is nowhere to be seen, not to say anything of the glottal stop (or ʻokina).

All known implementations follow the PC style tradition for the key between LSHIFT and Z.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the English (US International) layout with others.

English (UK).

Notes:

Official in the United Kingdom, Ireland and Hong Kong; also used in a few other English-speaking countries, with differing degrees of officiality.

The BS 4822 standard, published in 1994, mandated the layout seen in the top right alphanumeric block, but was withdrawn in 2008 without having ever been updated or superseded by a new document; current usage has flipped the characters | (U+007C, VERTICAL LINE) and ¦ (U+00A6, BROKEN BAR) and assigned the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑4, as seen in the bottom right alphanumeric block; the IBM specification was updated in 2000 with the latter change but not the former.

The flipping of the bars was quite probably done by Microsoft, perhaps even due to an inadvertent mistake, and forced by the company upon the world. Given that the vertical bar is an important character, while the broken bar is a legacy character that should have never existed in the first place, this modification turns out to not be a bad thing in this layout (unlike what happens in the Swiss layouts, where it’s definitely a detrimental change).

Besides the above change, Microsoft’s implementation adds the accented vowels Á/á, É/é, Í/í, Ó/ó and Ú/ú, used in Irish and Welsh, but not Ẃ/ẃ or Ý/ý, used in Welsh.

Despite the complex relationship the Republic of Ireland has with the English language (due to historical and political factors that will be avoided in this document), the English (UK) layout is still official in the country. In December 2021, the Official Languages Act of 2003 was modified, including a mandate for language standards that better protect and promote the Irish language; this will, at some undefined point in the future, result in the issuance of an official Irish national layout… that will surely look like Microsoft’s current implementation of this layout.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- BS 4822 standard.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the English (UK) national layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

- Islands: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

English (UK) Extended.

Notes:

This is a superset of the English (UK) national layout (with an exception — see below); it was designed with the explicit intention of supporting the Welsh language, something that its IBM internal identification number (166W) makes inescapably evident (English (UK)’s layout is 166). It also adds a few things intended for other languages, as described below.

As far as can be determined, this layout was actually created by Microsoft; it follows the current usage version of the English (UK) national layout, despite the BS 4822 standard having been still in vigour at the time of its creation.

Despite its declared goal, this layout’s design is rather poor: all seven vowel keys have their corresponding characters with acute accents on its tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers, and there are dead keys for the four diacritics used in Welsh: circumflex, grave and acute accents and the diaeresis (plus, for some reason, the tilde accent, which is not used in any part of the British Isles); the grave accent is in the base layer, replacing the backquote sign (`), while all the other diacritics are in the tertiary (AltGr) layer and in placements that suggest they were meant for occasional usage. None of these choices play along with the fact that the most-often used diacritic in Welsh is the circumflex accent.

This layout also adds the letter C with cedilla (Ç/ç), unused in Welsh. It’s unclear whether this was done to add support for the Manx language and/or the Norman-derived languages spoken in the Crown dependencies in the Channel Islands and/or for the benefit of a certain other neighboring Romance language.

The specification, as transcribed by IBM, omits the grave accent despite proclaiming the layout was “confirmed” as fully supporting Welsh; it also adds a macron (◌̄) dead key for the benefit of Cornish, which is pointless, given that this layout does not otherwise make any concessions to any historical grammar of any language spoken in the British Isles.

Due to Cornish being a recently-revived language, with a scant amount of speakers, and pretty much of interest only to linguists, it has been subjected to several competing ortographies. Unified Cornish, created in the early XX century, used macrons to mark long vowels. However, by the time IBM’s specification was written, it had been mostly replaced by Modern Cornish (also called “Revived Late Cornish”), which used circumflex accents instead. Later, in 2008, all competing ortographies for Cornish were replaced with the Standard Written Form, which uses no diacritics at all. This standard has been revised twice already, and some linguists continue to use the circumflex and grave accents and the diaeresis, so those diacritics could be reinstated in the future… but the macron surely won’t.

Given the described discrepancies, this document opts to register Microsoft’s choice of dead keys instead of what the IBM document states.

The dead keys present in this layout also add, if unofficially and clunkily, support for Scottish Gaelic and (modern) Irish.

Unsurprisingly, a significant percentage of Welsh speakers use a different “Welsh” layout, which also extends the English (UK) layout, places the diacritic dead keys in different positions and makes the seven vowel keys have their corresponding characters with circumflex accents on its tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers (as should have been done here in the first place).

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the English (UK) Extended national layout with others.

- Islands: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Irish.

Notes:

This Microsoft-made layout is an intermediate version between the English (UK) and English (UK) Extended layouts, with (presumably) little actual research about the needs of the Irish language — most notably, the absence of the overdot diacritic and the presence of the grave accent.

Private individuals have created several alternative layouts with the requirements of the Irish language in mind; all of them are better than this half-baked effort, which strongly looks like it was made to satisfy a whim or quickly check a box.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing this particular Irish layout with others.

- Islands: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Scottish Gaelic.

Notes:

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language still spoken in parts of the Highlands of Scotland; it must not be confused with Scots, a Germanic language prevalent in the Lowlands.

Scottish Gaelic uses the grave accent for all its vowels; it also used the acute accent on three (á, é and ó) until 1981, when it was discarded in an ortographic reform.

This Microsoft-made layout is an intermediate version between the English (UK) and English (UK) Extended layouts, like the Irish layout is, and comes off as just as half-baked and pointless. Given that the acute accent was eliminated several decades ago, it makes no sense to keep the direct assignments for all five vowels (plus a loanletter) with it, while the grave accent is restricted to a single dead key, even if it’s in the primary (base) layer.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- There is no dedicated Wikipedia entry for this layout.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Scottish Gaelic subnational layout with others.

Canadian (bilingual).

Notes:

This is the old standard keyboard layout in Canada; it was created to satisfy the legal requirements derived from the country’s recognition of both English and French as official languages. Even today, its presence in Quebec and other Francophone areas is ubiquitous, due to the limited adoption rate of the Canadian (multilingual) layout, but in the regions of the country with little or no French presence, the English (USA) layout is preferred.

Despite having been created with bilingualism in mind, this layout is generally known as “French Canadian” (or “Canadian French”, “French (Canada)”, etcetera). This term is also applied to the Canadian (intermediate) layout and (although to a much lesser degree) to the Canadian (multilingual) layout, further muddling the issue. This document prefers the name “Canadian (bilingual)” to help reduce confusion.

It does not help matters that a common sight in Canada are binational keyboards, containing the printed legends for both English (USA) layout and either the Canadian (bilingual) or the Canadian (intermediate) layout, and those are marketed and sold as “bilingual keyboards”.

This layout is obviously derived from the English (USA) layout; while it’s certainly nowhere as bad as the French (France) layout, a better job could have been done of it; the most glaring problems are: the inclusion of a dead key for the cedilla makes little sense if it’s only used to produce the Ç letter; the displacement of the apostrophe (’), less-than (<) and greater-than (>) signs comes off as unnecessary and detrimental to the overall layout… but not as bad as the displacement of the slash (/) sign actually is; the superscript characters ² and ³ could have been easily placed under AltGr‑2 and AltGr‑3.

This is one of very few national layouts that include the overline sign (¯).

Keyboards with this layout generally have legends in French in their modifier keys, but it’s unclear whether this is a requirement of its standard or is simply a common practice.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation (named “Canadian French”).

- Wikipedia entry (note the wrong, inconsistent names that are used).

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Canadian (bilingual) national layout with others.

Canadian (intermediate).

Notes:

This layout was seen on keyboards sold during the mid ’90s, before units with the hexalayered Canadian (multilingual) layout appeared. Actually, it looks like this layout is an early version of what became the Canadian (multilingual) layout, before the quinary and senary layers were added; the fact that said layout is a superset of this one reinforces this theory.

This layout is commonly referred to as “French Canadian”, as well as “ACNOR keyboard”, to distinguish it from the CSA keyboard (despite ACNOR and CSA being the same organization and both layouts quite probably coming from different editions of the same standard). This document prefers the name “Canadian (intermediate)” to help reduce confusion.

No PC keyboards with this layout are sold currently, but old units can be found with relative ease. Weirdly, however, a significant minority of the binational (USA+Canada) keyboards presently for sale use this layout for the Canadian legends.

On the other hand, Apple’s current “French (Canada)” layout is a lightly Apple-warped version of this layout, instead of either of the other two Canadian layouts. Apple’s old (“old” as in “M0110 keyboard”) layout, actually called “W. French”, was a heavily Apple-warped version of the Canadian (bilingual) layout; it was so horribly inadequate that Apple itself took the rare step of replacing it with its current layout.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Canadian (intermediate) national layout with others.

Canadian (multilingual).

Notes:

This is the current standard keyboard layout in Canada, developed with the intention of supporting both English and French and several other languages (with a clear bias towards Northwestern and Northern Europe); it’s governed by the CAN/CSA Z243.200-92 standard, which, unlike several other national layout standards, has been periodically revised by the CSA Group (formerly the Canadian Standards Association, known by its abbreviations CSA [English] and ACNOR [French]).

Not that the above matters, as this layout, despite being official in Canada, promoted by its government, and mandatory in the public sector, is not well liked; French-speakers prefer the Canadian (bilingual) layout, while the English (USA) layout is used wherever in the country there is little or no French presence.

The poor reception of this layout is evidently a result of its rather questionable design; quinary and senary layers are added for no real reason (as the ternary layer remains mostly empty and the quaternary layer entirely so), which require the transformation of the right Control key into a (right-side only) Shift2 modifier key to access them. Many of the character assignments within these superfluous layers are unintuitive and were clearly piled on gradually wherever space happened to be available, with little thought given to the overall design of the layout as a whole (and correctness, in a few glaring cases); this makes hard it to remember when exactly either of AltGr, Shift2 or Shift2‑Shift should be pressed to produce a particular symbol. Furthermore, the loss of the right Control key hinders general usability and produces unexpected results with some programs (not to say anything of some “custom” keyboards that lack that key because their designers think that if they themselves don’t use it, then no one else does, either, and can thus be omitted).

It would not be difficult to make a new, better “Canadian multilingual” layout that fixes the many problems this one has, and removes the unneeded quinary and senary layers… or actually keeps them, but reserved exclusively for a unified Syllabics layout.

IBM’s specification, pictured above, represents what the standard mandated in the late ’90s; that is quite outdated, as the current version, also pictured above, contains many later additions to the quinary and senary layers (while barely touching the ternary layer). Although not for sale anymore, older keyboards with the IBM-frozen version of the layout printed on their keycaps are not hard to find.

Uniquely, the standard mandates using icons instead of text legends for the modifier keys.

A commonly used name for keyboards with this particular layout is “CSA keyboard”.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (main) and IBM’s specification (supplement) (locally hosted copies).

- CAN/CSA Z243.200-92 standard.

- Microsoft’s implementation (named “Canadian French (Legacy)”; close to the late ’90s specification, although with a few weird changes).

- Microsoft’s implementation (named “Canadian Multilingual Standard)”; almost identical to the current specification).

- Wikipedia entry (English); Wikipedia entry (French).

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Canadian (multilingual) national layout with others.

English (USA) Dvorak.

Notes:

The Dvorak layout was created in 1936 as an (alleged) improvement over the QWERTY layout. Over the years, it has been subjected to several changes and has been standardized into the version seen above.

Row 1 is mostly unaltered with respect to the regular (QWERTY) English (USA) layout (this wasn’t the case in the original version of the Dvorak layout!). On the other hand, in rows 2, 3 and 4, most keys have been moved around: only three remain in the same positions, and ten others remain in the same row but have have been displaced to the left or to the right.

The homing keys become U and H, instead of F and J.

Despite the claims of improved typing seed, this layout’s level of adoption is limited, even among keyboard enthusiasts. During the early to mid-’80s, Apple shilled heavily the Dvorak layout, on their lines of Apple IIe and IIc computers, and not even that helped.

Given the scant usage this layout sees, there’s pretty much nothing established about what to do with the key between LSHIFT and Z if it should be present. Microsoft’s implementation of this layout simply places an extra \| (“backslash‑pipe”) key, following the PC style, as it already does in the regular (QWERTY) English (USA) layout.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the English (USA) Dvorak layout with others.

English (USA) Colemak.

Notes:

The Colemak layout was created in 2006 as another improvement over the QWERTY layout, that would also be less drastic of a change than the Dvorak layout is.

Only one non-letter alphanumeric key is moved around; the rest of the reassignments is restricted to the letter keys.

The homing keys become T and N, instead of F and J.

The Caps Lock key becomes another Backspace key.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- There is no Microsoft implementation of this layout.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the English (USA) Colemak layout with others.

Germanic and Nordic layouts.

Danish.

Notes:

Official in Denmark. The whole Kingdom of Denmark.

This layout is extremely similar to the Norwegian layout.

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E, and the character µ (U+00B5, MICRO SIGN) under AltGr‑M. Other implementations have copied this as well.

Microsoft derived the Faroese and Greenlandic layouts directly from this layout. Frankly, the Greenlandic layout is better at serving the needs of the entire country than the current version of the Danish layout, and its additions should be incorporated here wholesale.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Danish national layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Dutch.

Notes:

This used to be the standard keyboard layout in the Netherlands, but at some point (seemingly, during the late ’90s), it was abandoned in favor of the English (US international) layout, laid on top of ISO keyboards (although ANSI units are a common sight and ANSISO models can be spotted every now and then). Worse, the keyboards commonly sold in that country print the legends for the regular English (USA) layout, with the only addition of the euro sign (€) on the bottom-right corner of the 5 % keycap. Why aren’t the rest of the tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layer assignments printed is a mystery, but cost-saving and laziness are quite probably to blame.

It remains unknown whether the Dutch layout was explicitly abandoned in favor of the English (US international) layout, or if this switch occured due to some sort of gradual market force (or abuse of it!) in action. For that matter, it also remains unknown the true degree of officiality the Dutch layout did have in the past within the country; no (government) standards document regarding this matter has been discovered so far.

Logical layouts, PC-based or terminal-based, that pair opening and closing symbols in the same key (curly braces, less-than and greater-than signs, angle quotation marks, etcetera), always place the former in the base layer and the latter in the secondary (Shift) layer; the Dutch layout goes the other way around with the brackets for no apparent reason: ] is on the base layer, while [ goes up to the secondary (Shift) layer. Why on Earth was this done (especially considering that the < and > symbols are placed normally) might be one of those mysteries that shall never be solved.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Dutch national layout with others.

Faroese.

Notes:

Until recently, the Faroe Islands were an autonomous territory of Denmark; they now are a constituent country within the Kingdom of Denmark (and, unlike Greenland, that is probably not going to change).

This layout is a slightly modified version of (the Microsoft implementation of) the Danish layout, to which, besides its usual addition of the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) under AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E, and the character µ (U+00B5, MICRO SIGN) under AltGr‑M, the letter eth (Ð/ð) has been forced into the primary (base) and secondary (Shift) layers, immediately to the right of the Å key, displacing the dead keys for the diaeresis and circumflex accents into the tertiary (AltGr) layer in neighboring keys.

It does not escape notice that the Å key has not been touched, even though the Faroese language does not use the letter A with overring (Danish does, however, so…).

There simply is no point at all for this layout — its only change (the inclusion of the letter eth) has been better implemented in the Greenlandic layout. In fact, the Greenlandic layout better serves the needs of the whole Kingdom of Denmark than both the (current) Danish layout and the Faroese layout.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Faroese subnational layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this subnational layout.

Finnish Multilingual.

Notes:

This layout was created by the Finnish IT Center for Science, with the goal of having complete support for the Finnish language and minority languages spoken in Finland, plus support for many other languages that use the Latin alphabet. In 2008, the Finnish Standardization Association released it as the SFS 5966 standard and declared it the official national layout for Finland, superseding the Swedish and Finnish layout. In 2019, a few small changes were made and a revised standard was published.

This layout is a (true) extended version of the Swedish and Finnish layout. It adds support for the letters Š and Ž, required by the Finnish ortography for loanwords, several typographical symbols (following Finnish usage, such as placing the angled quotes “backwards”), a few extra letters used in languages other than Finnish, and thirteen dead keys for diacritics, in addition to the previously extant five.

Despite being a well-designed layout that should not pose any problems for adoption (as it’s a strict superset of the previous official layout, and corrects several of its omissions), its usage levels remain low; while it was immediately implemented in Linux, it has not been so, to this day, by Microsoft and Apple; this omission is particularly inexplicable in the case of Microsoft, which at the time the standard was published was keen on implementing a multitude of national layouts, including several dedicated to minority languages with very small amounts of speakers.

Private individuals have built their own implementations of this layout for Windows and MacOS to wade around this problem.

There is little to criticize in this layout: the only omissions of note are the Turkish dotted uppercase letter I (İ), given that the dotless lowercase non-counterpart (ı) is present, and the backquote (`), tilde (~) and caret (^) characters as directly available assignments instead of through a dead key, given the importance programming has in keyboard usage in Finland; AltGr‑1, AltGr‑Q and AltGr‑W are unused, so they could be placed there without issue.

Another further improvement would be to move the single, double and angled quotes to more sensible positions in the tertiary (AltGr) layer in the still available central area of the keyboard (this would also allow moving the comma dead key from AltGr‑Shift‑- to AltGr‑,, a much more intuitive position).

This is one of very few layouts that places the character (U+00A0, NO-BREAK SPACE) in AltGr‑space. Uniquely, the 2019 revision added the (U+202F, NARROW NO-BREAK SPACE) character as well, in AltGr‑Shift‑space.

The character – (U+2013, EN DASH) is located at AltGr‑-, while the character — (U+2014, EM DASH) is located at AltGr‑Shift‑M.

The stroke (not “bar” or “slash”) dead key is located under AltGr‑§, with an alternative placement under AltGr‑L, to cover the possibility of the corner alphanumeric key being unavailable (another piece of evidence of the importance programming does have in Finnish keyboard usage). This is not a true diacritic — instead, this dead key allows typing a few unrelated stroked letters: Đ/đ (not to be confused with the letter eth, Ð/ð, placed under AltGr‑D), Ǥ/ǥ, Ħ/ħ, Ł/ł and Ŧ/ŧ, plus Ø/ø (which is already available under AltGr‑Ö).

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- SFS 5966 standard.

- There is no Microsoft implementation for this layout.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Finnish Multilingual supranational layout with others.

German.

Notes:

Official in Germany and Austria.

The IBM specification (last updated in 1998) declares AltGr‑+ to be a dead key, but all known implementations make it instead into a regular key, which produces the (non combining, non diacritic) character ~ (U+007E, TILDE). To compound the issue, the DIN 2137 document (the current standard governing this layout in Germany) has declared it as a regular key since at least its 2012 edition; it’s not known if this was a de facto change that was adopted at some point by the standard, or if the IBM specification was wrong in the first place. The confusion is further deepened after studying the German-derived national layouts that place the tilde in the same physical key combination: most of the Nordic layouts (with the possible exception of the Icelandic one) keep it as a dead key, while Spanish (Latin America) and (perhaps) Icelandic have made it into a regular key (as the German layout seems to have).

The character under AltGr‑M is µ (U+00B5, MICRO SIGN) and not μ (U+03BC, GREEK SMALL LETTER MU) (albeit the symbol is evidently derived from the letter).

In 2008, Unicode added the uppercase form of the eszett ligature ẞ (U+1E9E, LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S). The standard for the German layout was rewritten in 2012; the new version kept the then-extant layout as “T1”, but did not add this character, and created “T2” and “T3” extended/specialized layouts, which do add it under AltGr‑H. Meanwhile, Microsoft added the uppercase eszett to its implementation of the German layout (now “T1”), under AltGr‑Shift-ß, and has kept it there instead of moving it so it will be in accordance to the DIN standard.

Although this is at its core a layout codified for the ISO physical variant, ISANSI versions of this layout exist, thanks to the “HADapter kit”, which provides a replacement 1.5U #’ key in row 2 (plus a 1.0U #’ key in row 1, for keyboards with an HHKB-style physical layout).

This is one of the few layouts that require the modifier keys to have legends in its own language instead of allowing them to remain in English («Strg» for “Ctrl”, «Einfg» for “Ins”, etcetera).

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- DIN 2137 standard.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- HADapter group buy thread on Deskthority.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the German supranational layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this supranational layout.

Greenlandic.

Notes:

Until recently, Greenland was an autonomous territory of Denmark. It now is a constituent country within the Kingdom of Denmark (not a member kingdom of the Crown of Denmark, although this may change in the future). Greenlandic people were and still are Danish citizens; Danish was the official language until 2009, when Greenlandic took that role. Despite that, Danish continues to be widely spoken.

This layout is an extended version of (the Microsoft implementation of) the Danish layout, to which, besides its usual addition of the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) under AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E, and the character µ (U+00B5, MICRO SIGN) under AltGr‑M, a few letters have been added in the tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers of the keys K, D, P and S: respectively, ĸ (kra, used until 1973 in the Greenlandic language; it still has presence in one dialect of Inuktitut, spoken in Canada), Ð/ð (eth, used in Faroese), Þ/þ (thorn, used in Faroese and Icelandic) and, for some reason, ß (the German eszett ligature, inexplicably only in its lowercase form).

Other than the letter kra, there is no real reason for having bothered to make a “separate” layout for the Greenlandic language. Actually, neither the Greenlandic nor the Faroese layouts should have been created in the first place; instead, the Danish layout should have been revised, adding the extra letters seen here, in their exact same assignments, as well as the uppercase form of the eszett ligature (ẞ) and perhaps even the angle quotation marks (« »). This “new” Danish layout would better serve the needs of all people (Danish, Faroese and Greenlanders) within the Kingdom of Denmark.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- There is no dedicated Wikipedia entry for this layout.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Greenlandic subnational layout with others.

Icelandic.

Notes:

Official in Iceland.

Unusually, this national layout, at least as defined in the IBM specification (last updated in 2000), places the acute accent dead key in both the base layer and the secondary (Shift) layer of the same key. Microsoft’s implementation seems to get this wrong, putting an unneeded apostrophe in the secondary (Shift) layer assignment; however, this and other differences (notably, tilde ceases to be a dead key, while the backquote becomes one) could be derived from the 2015 standard, the text of which has not been obtained yet.

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E, and the character µ (U+00B5, MICRO SIGN) under AltGr‑M. Other implementations have copied this as well.

The -_ key is displaced one position to the right with respect to the English (USA) keyboard, but remains in row 1.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- ÍST 125:2015 standard.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Icelandic national layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Norwegian.

Notes:

Official in Norway.

This layout is extremely similar to the Danish one.

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E, and the character µ (U+00B5, MICRO SIGN) under AltGr‑M. Other implementations have copied this as well.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Norwegian national layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Norwegian with Sami.

Notes:

The Sami languages are spoken in the northern reaches of the Scandinavian Peninsula and the neighboring Kola peninsula; they have been recognized as minority languages in Norway, Sweden and Finland.

This Microsoft-made layout is a (true) extended version of the Norwegian layout, to which the extra letters and letters with diacritics required to write in almost all the known Sami languages (not just the ones spoken in Norway) have been added in the tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers; the letter Ü, used in Ume Sami, is inexplicably missing.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Norwegian with Sami supranational layout with others.

Swedish and Finnish.

Notes:

Official in Sweden; official in Finland until 2008, when it was replaced by the Finnish Multilingual layout, although this one continues to be the majority option in the country.

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E, and the character µ (U+00B5, MICRO SIGN) under AltGr‑M. Other implementations have copied this as well.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Swedish and Finnish binational layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this binational layout.

Swedish and Finnish with Sami.

Notes:

The Sami languages are spoken in the northern reaches of the Scandinavian Peninsula and the neighboring Kola peninsula; they have been recognized as minority languages in Norway, Sweden and Finland.

This Microsoft-made layout is a (true) extended version of the Swedish and Finnish layout, to which the extra letters and letters with diacritics required to write in almost all the known Sami languages (not just the ones spoken in Sweden or Finland) have been added in the tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers; the letter Ü, used in Ume Sami, is inexplicably missing.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Swedish and Finnish with Sami supranational layout with others.

Swiss.

Notes:

The Swiss national layout was designed to support one Germanic language (German) and three Romance ones (French, Italian and Romansh); it’s listed in this section because it was evidently derived from the German layout.

This layout’s specification, governed in its latest revision by the SN 074021:1999-01 document, defines two “modes” of operation: in the “German” mode, the keys in the positions D11, C10 and C11 (see above) have the characters ü, ö and ä, respectively, in the base layer, while the characters è, é and à, respectively, are in the secondary (Shift) layer; in the “French” mode, those assignments are flipped (è, é and à, respectively, are in the base layer, while ü, ö and ä, respectively, are in the secondary (Shift) layer).

This modes shenanigan is so far off the regular behaviour of a keyboard, that all known implementations in differing operating systems simply split the Swiss layout into two separate ones: “Swiss (German)” and “Swiss (French)”.

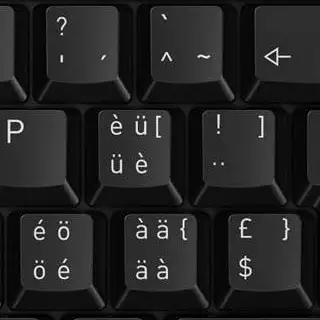

To further muddle the issue, keyboards sold in Switzerland print both varieties in the aforementioned three keycaps, leading to visually confusing labels:

Note how in the first keyboard, symbols in the tertiary (AltGr) layer are consistently front-printed, while in the second one, some are printed in the bottom right corner (this is the correct position) and others in the top right one (falsely implying they’re part of the quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layer).

Problems don’t stop there, though: in both “modes”, those three keys produce said six vowels with diacritics… but only in their lowercase forms; to produce them in uppercase, Caps Lock must be turned on. To mitigate this limitation, and to allow typing the remaining accented letters, dead keys for every major diacritic (diaeresis/umlaut, and the acute, grave and circumflex accents… plus the tilde, which is not used in any language spoken in Switzerland) are included…

… but don’t let the letter C with cedilla hear about it, as its uppercase version (Ç) can’t be typed at all using this layout.

This is an unequivocally poorly designed layout — it would have been much better to assign the diacritic dead keys directly to the D11, C10 and C11 keys (where they would have been more comfortable to use), get rid of the nonsensical vowel dualities and take advantage of the freed-up space in the remaining keys to include other symbols: besides the incompetent treatment of the C with cedilla, there is no good excuse for not having included, at the very least, the angle quotes or guillemets (used in German and French) and the Æ/æ (used in Italian and French), Œ/œ (used in French) and even ẞ/ß (used in German, even if Swiss Standard German doesn’t) ligatures.

Despite its serious flaws and omissions, this is (are) the official layout(s) in Switzerland. Weirdly, but not surprisingly, the Swiss (German mode) layout is also official in Liechtenstein; in addition to that, the Swiss (French mode) layout is, unbelievably, official in Luxembourg, although a large percentage of its population prefers using the French (Belgium) layout.

Linux’s implementations of most national layouts include the lowercase eszett ligature (ß) under AltGr‑S; this is the case of the Linux implementation of the Swiss layouts, too.

Microsoft’s implementations of the Swiss layouts are particularly deficient. To wit:

- Both implementations swap the placement of the | (U+007C, VERTICAL LINE) and ¦ (U+00A6, BROKEN BAR) symbols for no apparent reason. To make things worse, there is no agreement over this among manufacturers, so it’s easy to find modern keyboards with those symbols printed in either the right way or the Microsoft way. Unlike what happens in the English (UK) layout, this flipping of the bars has detrimental effects for the user (the vertical bar character is heavily used, and in this implementation is located in a hard-to-reach spot).

- Both implementations, again for no apparent reason, also place needless additional assignments for the ° (U+00B0, DEGREE SIGN) and § (U+00A7, SECTION SIGN) symbols in the tertiary (AltGr) layer, in AltGr‑4 and AltGr‑5, respectively. The latter is particularly surprising, because Microsoft has the habit of including an additional placement of the € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) symbol in AltGr‑5 on the European layouts that normally place it in AltGr‑E, as is the case here.

- The Swiss (French) layout does not implement the Caps Lock trick, meaning that the characters È, É, À, Ü, Ö and Ä can only be typed in with the diacritic dead keys.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification — German mode (locally hosted copy).

- IBM’s specification — French mode (locally hosted copy).

- SN 074021:1999-01 standard.

- Microsoft’s implementation — German mode.

- Microsoft’s implementation — French mode.

- Microsoft’s implementation — Luxembourgish; identical to the Swiss (French) layout.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Swiss (German) national layout with others.

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Swiss (French) national layout with others.

Baltic layouts.

Estonian.

Notes:

Official in Estonia.

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E. Other implementations have copied this as well.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Estonian national layout with others.

- NorDeUK+++: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Latvian.

Notes:

IBM’s specification defines two different layouts for the Latvian language: “QWERTY” and “Ergonomic”; they follow, respectively, the Latvian standards LVS 24-93 and LVS 23-93 (note that despite their numbers, the former is older than the latter by a few months). The “QWERTY” layout is generally used in the country, while the latter is barely utilized.

The “QWERTY” layout is essentially the same as the English (USA) layout, PC style, to which the specific requirements of the Latvian language have been added on to the tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers; the only changes in the primary (base) and secondary (Shift) layers are the apostrophe/quote key (’/”), for which both assignments are now dead keys, and the (home row) backlash/pipe key (\/|), which now contains the degree sign and the broken bar character (A remnant from a layout for old terminals? That seems to be the least implausible explanation); the backslash and pipe characters are still available in the extra alphanumeric key.

The inescapable oddities and anomalies present in this layout suggest that rather little care was put into it, allowing egregious errors to pass through: the apostrophe and quote signs are now dead keys, but are duplicated as-is in the AltGr layers of the same key; there is no logical reason for having taken the backslash and pipe characters off from… the backslash/pipe key; in the number row, several symbols have been added to the quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layer, even though space in the tertiary (AltGr) layer is readily available; the degree sign is duplicated; the multiplication sign is present but the division sign is nowhere to be seen; AltGr‑- and AltGr‑Shift‑- are supposed to be, respectively, the en dash and the em dash (in THAT order), but the chart shows, instead of an en dash, what is clearly an overline sign… which is something that would actually make sense, given the Latvian language uses the macron diacritic. In light of these problems, the fact that the no-breaking space has been placed at AltGr‑1 instead of AltGr‑space looks more like a whimsical choice rather than the error it probably actually is.

The “Ergonomic” layout (also known as “ŪGJRMV”, following the usual layout-naming formula) has been, allegedly, designed to optimize writing in Latvian. The rather radical rearrangement of the letters (out of thirty nine letters, only two remain in the same position, and barely five more manage to stay in the same row and pair of layers) may well be perfect in this regard (G with comma and K with comma notwithstanding), but its handling of typographical symbols leaves a lot to be desired — barely any errors in the “QWERTY” layout have been corrected here, and some further mistakes have been commited, the worst one being the inexcusably sinful displacement of the curly braces to the quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layer.

Okay, I’ll say it: who is Šusilda, and why was her name sneaked onto the home row?

It’s important to note that the Latvian language uses a diacritic comma on its letters G, K, L and N (plus, formerly, R), not a diacritic cedilla; both layouts opt for the latter instead of the former because the Unicode Consortium still has not disunified both diacritics. If that ever happens, both layouts will need to be updated, to produce the correct characters (and perhaps add the still missing D with comma, required to write in Livonian).

Microsoft offers two different implementations of the “QWERTY” layout, both slightly different than what the specification for it declares, and one more for the “Ergonomic” layout, which is almost identical to its corresponding specification, but with an error so grievous, it has to be seen to be believed (hint: look at the key F in the number row).

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation (named “Latvian (QWERTY)”, based on “QWERTY”).

- Microsoft’s implementation (named “Latvian (Standard)”, based on “QWERTY”).

- Microsoft’s implementation (named “Latvian”, based on “Ergonomic”).

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Latvian (“QWERTY”) national layout with others.

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Latvian (“Ergonomic”) national layout with others.

Lithuanian.

Notes:

The Lithuanian National Standard LST 1582:2000 makes official and mandates the layout seen in the top right alphanumeric block, but the actual degree of usage of this layout is rather lower than it should be (see below).

Unlike other languages with a convoluted mess of conflicting layouts, the ones used in Lithuania are well-known and well-documented enough to clear up their history.

When personal computers started showing up in Lithuania (at about the same time the USSR was collapsing, which allowed the country to declare its independence), support for the Lithuanian language on (Western) software and hardware was extremely limited. At first, given that the keyboards imported to the country were units with the English (USA) layout, the first Lithuanian layout was made by simply replacing the keys 1 through 8 and =+ in the number row with dedicated keys for the required letters with diacritics (ogonek, caron and overdot).

This first layout came to be colloquially known as “numeric” (probably in a display of contrarian humor, because it lacked most of the numbers in the main alphanumeric block). Unsuprisingly, it was generally regarded as defficient, as it was uncomfortable for writing in Lithuanian (due to the high number of letters in the number row), required the presence of a numeric keypad to type numbers, and lacked many heavily used typographical symbols. It should be noted that the “weird” placement of the letter Ž followed the placement of the letter X, as was the standard in Lithuanian typewriters.

The “numeric” layout never was a documented standard to begin with — it simply won out through inertia and lack of true competition through the then-small user base.

In 1989, the first standard for a Lithuanian keyboard, LST 1092-89, was published. This layout (not pictured above) was complex and convoluted and gained no traction whatsoever, ending up no more than an obscure footnote.

A new standard, LST 1205-92, published in 1992, attempted to replace the “numeric” layout; it was directly derived from the preexisting standard for Lithuanian typewriters, which places the numbers in the secondary (Shift) layer of the number row, has a rather particular arrangement of the basic typographical symbols in its base layer (albeit not pointlessly chaotic, as the French layouts do have), and places all the letters with diacritics in the main rows. The only notable differences between the 1992 standard and its source (the typewriter standard) are that it swapped the letters F and Š, so the former would retain the same placement as in Western keyboards, and eliminated the letter X (in Lithuanian, the letter F is used only on loanwords; Q, W and X are entirely absent, and the first two of those had already been expelled from typewriters).

The 1992 standard was also deemed to be insufficient, as the lack of three Latin letters made it rather challenging to write in English and other European languages (or, for that matter, to une_uivocally e_plain the _eirdly _ui_otic _ays of the layout itself), and the absence of several important typographical symbols impeded programming.

It does not escape notice that not just the numbers and symbols are swapped in the number row — the same was done to the -_, =+ and \| keys, which became, respectively, _-, += and |\. Information regarding the 1992 standard is scant, but the few extant signs suggest that it was made with BAE keyboards in mind. EEEEWWWW! Another good reason for its repeal!

In 2000, the LST 1582:2000 standard superseded the previous one and corrected its mistakes. Notably, it swapped the letters F and Š, in accordance with the typewriter standard.

With all the above said, the 2000 layout should be the mainly used one, with all other options left behind… but inertia and the misguided support of major OS manufacturers have allowed the “numeric” layout to continue to be the most popular one in the country, despite its serious shortcomings and problems.

Windows provides implementations of the three Lithuanian layouts: the “numeric” layout is called “Lithuanian”, the “1992 standard” layout is inexplicably named “Lithuanian (IBM)” and the “2000 standard” layout gets referred to as “Lithuanian Standard”. Linux distributions vary, but they generally provide the same options, copying whatever Microsoft may have done before. Apple, on the other hand, provides only one “Lithuanian” layout, which is an Apple-warped version of the “numeric” layout.

OS/2 had a rather unique implementation (essentially the same as the English (USA) layout, upon which the Lithuanian letters with diacritics were added to an entirely separate “language” layer for the corresponding keys, as dictated by the 1992 layout). Its chart id is 456, which strongly suggests that it indeed corresponded to the IBM’s specification of the 1992 standard, one that was later rescinded in favor of the specification for the 2000 standard.

Microsoft’s implementation of the “numeric” solves its omissions by adding the numbers and the missing typographical symbols to the respective keys in the tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers, in the same respective order as in the English (USA) layout; it can not be overstated how incredibly impractical this is for regular usage.

The euro sign is also added, in AltGr‑E.

The “2000 standard” layout has some further peculiarities to comment on:

- This is one of very few layouts that includes the character – (U+2013, EN DASH); why the character — (U+2014, EM DASH) is not included, as some other national layouts do, is unknown.

- This is one of very few layouts that places the character (U+00A0, NO-BREAK SPACE) in AltGr‑space.

- The entire layout defines no dead keys whatsoever, despite the acute accent (´) having been added to the corner (E00) key. Lithuanian does use acute, grave and tilde accents, and it seems this omission was an oversight in the standard. Layout implementations built by private individuals, including some of the people involved in the creation of the 2000 standard (!!), DO make the corner key into a triple-dead key, producing letters with acute, grave and tilde accents.

- The 2000 standard (and possibly the 1992 standard before it as well) mandates that the modifier keys’ legends be translated to Lithuanian instead of remanining in English («Lyg2» for “Shift”, «Lyg3» for “AltGr”, «Įvesti» for «Enter», etcetera).

The “2000 standard” layout is, certainly, good enough for the Lithuanian language, but it does look somewhat weird; its absolute lack of dead keys is surprising, considering how heavily does Lithuanian use diacritics, and its rather particular placement of common typographical symbols makes it difficult for foreigners to use. If the demand for a “real QWERTY” keyboard layout came, one could be crafted without too much trouble, by placing the letter Ė in the D10 key and adding dead keys for the ogonek and the caron in the C10 and C11 keys, respectively; a few further adjustments would be needed so the layout would be closer in its general arrangements to what’s common in the neighboring European layouts (the keys ,;, .: and -_ in B08, B09 and B10, for example).

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (2000 standard) (locally hosted copy).

- IBM’s specification (Microsoft’s “numeric” implementation) (locally hosted copy).

- Lithuanian National Standard LST 1582:2000, as referenced by IBM’s specification (Internet Archive copy).

- Lithuanian National Standard LST 1582:2000 — currently hosted copy; contains the same information, plus extra comments on the history of this national layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation (2000 standard).

- Microsoft’s implementation (1992 standard).

- Microsoft’s implementation (“numeric” layout).

- Wikipedia entry (2000 standard).

- Wikipedia entry (“numeric” layout).

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Lithuanian national layout with others.

Mediterranean Romance layouts.

Italian.

Notes:

The initial Italian layout that IBM compiled was given the ID 141; it was superseded in 1991 by an improved layout (ID 142), which modified the assignments of a few typographical symbols under the tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layers, and added the previously missing backquote (`) and tilde (~) characters.

Despite the aforementioned improvements, the older layout is the one actually used in Italy, while the newer, better one remains almost unknown. History is lacking in this, but it seems that the Italian (142) layout was engulfed in the disaster that sank OS/2, and vendors never bothered to update their offerings… despite Microsoft itself actually adding support for the newer layout not that much later; to this day, Microsoft lists the older layout [Italian (141)] as the main layout for the Italian language, while the new one [Italian (142)] is available as an alternative.

This is one of the few layouts that require the modifier keys to have legends in its own language instead of allowing them to remain in English («Fine» for “End”, «Invio» for “Enter”, etcetera).

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E. Other implementations have copied this as well.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy). This is for the 142 layout; the 141 layout’s specification is not available.

- Microsoft’s implementation (Italian (142)).

- Microsoft’s implementation (Italian (141)).

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Italian (142) national layout with others.

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Italian (141) national layout with others.

- BRESLAPTIT: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

- Keyboard layouts for Windows: New Italian: a proposed new version of the Italian layout.

Portuguese (Brazil).

Notes:

Official in Brazil.

The ABNT NBR 10346:1991 standard mandates one extra key in row 4, between the ;: key (placed where the /? key is in an English (USA) keyboard) and RSHIFT; indeed, plenty of keyboards with this extra key do exist. Some implementations, Microsoft’s included, provide a workaround for keyboards that lack it by making extra assignments under the tertiary (AltGr) layer for the three symbols (slash, question mark and degree sign) that would otherwise be inaccessible.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- ABNT NBR 10346:1991 standard.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

- Source for the image file Brazilian 104-key ABNT2 keyboard.jpg, by Wikipedia user rsjsouza.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Portuguese (Brazil) national layout with others.

- BRESLAPTIT: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Portuguese (Portugal).

Notes:

Official in Portugal. Its degree of usage in other Portuguese-speaking countries (besides Brazil) is unknown.

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E. Other implementations have copied this as well.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Portuguese (Portugal) national layout with others.

- BRESLAPTIT: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

Spanish (Latin America).

Notes:

Official in all(*) the Spanish-speaking countries in the American continent… although this officiality is probably not much more than some IBM employee in an Armonk office declaring so back in the day, something that no one has ever bothered to question ever since.

(*) IBM’s specification lists explicitly every Spanish-speaking country in the American continent, Puerto Rico included… with the surprisingly surprising omission of Cuba; why something like this might have happened in a large, resourceful, known for its high quality work, company headquartered in the United States of America… may be one of those confusing mysteries that is never, ever satisfyingly explained. Or not. Whatever.

The “Latin America” moniker is a serious misnomer: support for Portuguese (and French, for that matter) is worryingly incomplete — the characters Ç (U+00C7, LATIN CAPITAL LETTER C WITH CEDILLA) and ç (U+00E7, LATIN SMALL LETTER C WITH CEDILLA) are nowhere to be seen, while the extra diacritics are present but look like they were tacked on for occasional usage only. It doesn’t help matters that the IBM specification itself states “Spanish speaking Latin America” in its description!

The IBM specification declares ~ (U+007E, TILDE) to be a dead key, but all known implementations make it into a regular key instead, further degrading Portuguese support.

This is one of the few layouts that require the modifier keys to have legends in its own language instead of allowing them to remain in English («Bloq Mayús» for “Caps Lock”, «Intro» for “Enter”, etcetera).

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Spanish (Latin America) supranational layout with others.

- BRESLAPTIT: a possible international kit that would cover this supranational layout.

- Keyboard layouts for Windows: Latin American Extended: an extended version of this layout.

Spanish (Spain).

Notes:

Official in Spain; also sees varying degrees of usage in other Spanish-speaking countries.

The letter C with cedilla (Ç/ç) was added for the benefit of the Catalan language (acting as a replacement for the proper ce trencada). For the longest time, this layout completely lacked the tilde (~) character (!!), either as a regular or as a dead key, making this layout nigh-useless for writing in Portuguese and for computer programming and administration; it was finally added recently, as a dead key under AltGr‑4.

Tilde absence or not, the Spanish (Spain) layout is generally considered to not be as well suited for usage in programming as the Spanish (Latin America) layout is, which may be a good part of the reason the latter has managed to avoid abandonment.

This is one of the few layouts that require the modifier keys to have legends in its own language instead of allowing them to remain in English («Supr» for “Del”, «Av Pág» for “Page Down”, etcetera).

Microsoft’s implementation assigns the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) to AltGr‑5 in addition to AltGr‑E. Other implementations have copied this as well.

Sources and non-sources:

- IBM’s specification (locally hosted copy).

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- Wikipedia entry.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Spanish (Spain) national layout with others.

- BRESLAPTIT: a possible international kit that would cover this national layout.

- Keyboard layouts for Windows: Spanish Extended: an extended version of this layout.

Spanish Variation.

Notes:

This is, truly, an undead layout, with a rather obscure and weird origin.

Unlike several other languages, there was no early standard for a Spanish layout on computer keyboards. Besides a QWERTY arrangement, plus the Ñ key placed immediately to the right of the L key, each early computer architecture that supported the Spanish language had its own layout for it, a sorry state of affairs… that was actually an improvement over typewriters: no Spanish typewriter standard existed at all, and layouts not only differed from manufacturer to manufacturer but, far too frequently, from line to line within the same company.

Generally speaking, most but not all of those typewriter layouts fell into two groups, with the placement of dead keys for diacritics as the main distinguishing factor:

- Two dead keys, placed immediately to the right of the Ñ and P keys; they housed, respectively, the acute accent and the diaeresis, and the grave and circumflex accents. Also, the letter C with cedilla (Ç/ç) was generally present, in wildly varying placements (and in lowercase form only, in older units).

- One dead key, placed immediately to the right of the P key; it housed the acute accent and the diaeresis. Also, the C with cedilla was absent in the majority of cases.

During the early to mid ’80s, IBM spearheaded the push for standardization, making… not one but two standard layouts for the Spanish language, which are what we now call, respectively, Spanish (Spain) and Spanish (Latin America). All should have been well and good, unnecessary duplication and defficiencies of both layouts notwithstanding, but…

A third, small, group of typewriter layouts placed the Ç key immediately to the right of Ñ, added an Ŀ key to the right of P as well, and placed three dead keys (for the acute and grave accents and the diaeresis), generally to their right; typewriters like this were manufactured by, at least, Olivetti, Olympia and Canon. When Olivetti started making computers, their initial models for the Spanish market used a version of this layout as well, although this didn’t last for long; by the late ’80s, Olivetti keyboards had switched to the Spanish (Spain) layout.

IBM did not support or document at all this layout, for the obvious reason; indeed, it’s nowhere to be seen in PC-DOS. However, given that at the time Olivetti had a large share of the market in Spain, Microsoft implemented it… albeit it was included only in the version of MS-DOS shipped with Olivetti computers. Later, after Olivetti had abandoned this layout, Microsoft failed to discontinue it and keeps it in the roster to this day, despite the fact that no keyboards with this layout exist, other than the few surviving units produced by Olivetti more than three decades ago.

As such, this can be called a “nullinational” layout, instead of “national” or “supranational”, as it’s official nowhere.

The only reference for this layout are the Olivetti keyboards themselves, which were sold in two distinct varieties: one was a hybrid of the XT layout and the AT layout; the other used the Enhanced layout. Microsoft’s implementation is also pictured above, as it’s the only extant one (disregarding some copycats, which ape Microsoft’s layouts wholesale without bothering to check whether they ought to bother or not) and contains several differences.

In the Olivetti keyboards mentioned above, the hybrid layout units sport English legends in the modifier keys, except for the Enter key, which is labeled as “Intro”; the Enhanced layout units have modifier keys with legends in Spanish, coinciding with the Spanish (Spain) layout.

In the Catalan language, spoken in parts of Spain, an interpunct is used to indicate that two adjacent letters L do not form the phoneme /ʎ/ and must be pronounced separately («al·lèrgia», «col·legi», etcetera); this is, therefore, an independent symbol, not a diacritic that is applied to the first letter.

Some typewriters incorporated the letter L with a middle dot as a single character due to a typographical restriction, one that does not exist on computer systems; nevertheless, some computer architectures made the mistake of including it in their character sets. It’s for compatibility with those that Unicode defines the code points Ŀ (U+013F, LATIN CAPITAL LETTER L WITH MIDDLE DOT) and ŀ (U+0140, LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH MIDDLE DOT), but they are marked as deprecated and should not be used. Note that both versions of this layout, pictured above, place the appropriate interpunct character in Shift‑'.

Microsoft’s implementation removes the inappropriate “letter” and places the multiplication and division signs in its place, albeit awkwardly. It also adds a dead key for the tilde diacritic, places the character € (U+20AC, EURO SIGN) under AltGr‑E (despite the very obsolete pseudo-sign for the peseta remaining), and replaces the caret with a dead key for the circumflex accent. Worryingly, several assignments from the tertiary (AltGr) layer of the Spanish (Spain) layout are mixed in, resulting in the inappropriate removal of the ° (U+00B0, DEGREE SIGN) and º (U+00BA, MASCULINE ORDINAL INDICATOR) characters.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout. (mind you, there couldn’t possibly be one)

- Microsoft’s implementation.

- There is no dedicated Wikipedia entry for this layout.

See also:

- The Interactive Comparator of Different National Layouts on a Computer Keyboard. allows comparing the Spanish Variation nullinational layout with others.

Spanish-Guarani.

Notes:

Guarani is a language mainly spoken in Paraguay, where it’s official along with Spanish; it also has presence in neighboring parts of Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia.

This layout is a superset of the Spanish (Latin America) layout (with an exception — see below) that adds incomplete support for the Guarani language.

This layout was actually created by Microsoft, with the name “Guarani”. It’s listed here instead as “Spanish-Guarani”, because it’s still a layout made for Spanish, and to which support for Guarani has been added later, instead of being a layout designed from the ground up with the primary objective of supporting Guarani, or even of supporting both languages with equal weight.

This layout adds tertiary (AltGr) and quaternary (AltGr‑Shift) layer assignments for the tilded letters that Guarani uses: Ã/ã, Ẽ/ẽ, Ĩ/ĩ, G̃/g̃, Õ/õ, Ũ/ũ and Ỹ/ỹ (G̃/g̃ was actually forgotten in the initial version of this layout, released in Windows 8.1; this omission was corrected when Windows 10 came out), and pointlessly turns the tilde symbol (in AltGr‑+) into a dead key (it can only produce the six vowels that already have direct assignments in the tertiary and quaternary layers).

This layout was created relatively recently, and was revised at least once… yet it still lacks the letter puso or saltillo (Ꞌ/ꞌ) for no good reason. While we’re at this, it would have been pretty neat to have also added the letter C with cedilla (Ç/ç), turn back the tilde symbol into a regular key assignment (or at least place it elsewhere), and perhaps even add the guarani (₲) and euro (€) signs.

In April 2022, this layout received another update (only on Windows 11, not on Windows 10); the guarani (₲) sign and the character ʼ (U+02BC, MODIFIER LETTER APOSTROPHE) [acting as a stand-in for the proper letter puso or saltillo (Ꞌ/ꞌ)] have been added. No such luck with the rest of the wish list.

It remains unknown whether this layout has been adopted as official in Paraguay, or if it even sees a significant degree of usage.

Sources and non-sources:

- There is no IBM specification for this layout.

- Microsoft’s implementation.

See also: